Early Coney Island History: A Tale of Mutiny at Manhattan Beach (1830)

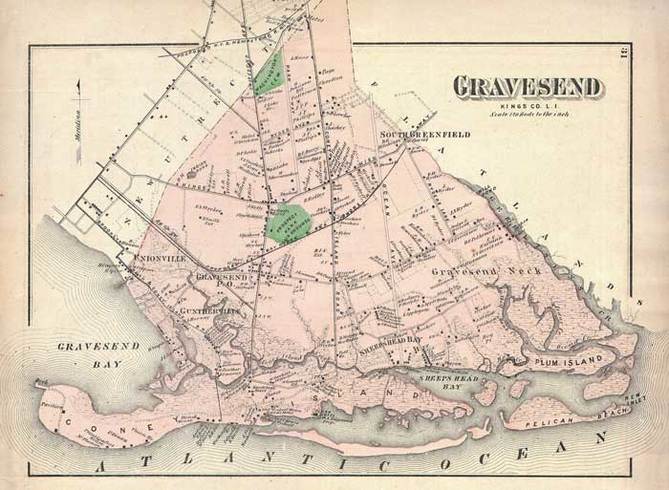

Map of Gravesend dating to 1873, showing Pelican Beach at the bottom right; today, that beach is underwater (Credit: Wikimedia Commons, provided by http://www.geographicus.com)

Map of Gravesend dating to 1873, showing Pelican Beach at the bottom right; today, that beach is underwater (Credit: Wikimedia Commons, provided by http://www.geographicus.com)

On November 9, 1830, the brig ‘Vineyard’ sailed from New Orleans for Philadelphia with a cargo of cotton, sugar, and molasses. Unknown to the crew, the ship also carried Mexican gold and silver coins valued at $54,000 in two sea-chests consigned to a prominent citizen of Philadelphia, Stephen Girard.

While at sea, Wansley, the ship's cook and steward, somehow found out about the money. He then plotted with multiple crew members - Henry Atwill, Aaron Church, Robert Dawes, and Charles Gibbs - to kill the captain and mate, and steal the money. Two other members of the crew, John Brownrigg and James Talbot, knew nothing of what was planned.

Shortly after midnight, when the ship was off Cape Hatteras, Wansley bludgeoned Captain William Thornby to death with a pump-brake, while the other mutineers hunted down and beat the mate, Mr. Roberts. Both Thornby and Roberts were then thrown overboard. Roberts was still alive at the time and tried to swim alongside the ship, pleading for his life, to no avail.

Brownrigg and Talbot, terrified by what they had seen, drew their knives for protection and fled aloft into the riggings. They were urged by the mutineers to come down and join them in sharing the treasure. Assured that they could keep their weapons, the two had no alternative but to comply.

The mutineers then set course for New York, bypassing the mouth of the Delaware River leading up to Philadelphia.

When they were off Southampton, Long Island, they decided to scuttle the ship. Brownrigg, Dawes, Gibbs, and Wansley got into the larger of the ship's two lifeboats with a chest containing $31,000; Atwill, Church, and Talbot got into the other rowboat with the remaining $23,000.

Just as the Vineyard was disappearing below the surface of the water, a gale blew up from the east, driving the lifeboats westward. They couldn't land in the wild surf, and were driven by wind and tide past several inlets.

Making for Rockaway Inlet, the smaller boat capsized, drowning its occupants. The other boat was taking on water faster than it could be bailed out. In a panic, the four aboard began to throw bags of coins into the sea to lighten the craft.

Finally, they reached Pelican Island, and got ashore. This island, now under water, was between Barren Island and Manhattan Beach, and had narrow channels between both. The channel at the Barren Island side was fordable at low tide.

There was a house on Barren Island occupied by John Johnson, his wife and children, and his brother, William. The mutineers, soaked and freezing, decided to bury the loot, now down to $5,000, and seek shelter in the house. They told the Johnsons that their captain, mate, and three members of the crew had been washed overboard in a storm that sank their ship. John Johnson offered them food and lodging for the night.

When the others were asleep, Brownrigg awakened John and William Johnson, revealed what had actually occurred, and told them where the money had been buried. John said that he and William would row the four of them to Sheepshead Bay in the morning, and that Brownrigg should tell the police there what had happened. The plan of the pirates was to hire a rig at Sheepshead Bay, return to Pelican Island for the money, row back to Sheepshead Bay, and drive to the city.

The next morning, the Johnsons rowed the four to Sheepshead Bay, left them there, rowed back to Pelican Island, dug up the money, and buried it elsewhere.

Meanwhile, Brownrigg was informing the police of the murders he had witnessed, and told of the buried money. The three accused killers were sent to a jail in Flatbush, while the police brought Brownrigg to the buried treasure, only to find it missing.

Further questioning of Brownrigg by the authorities made them suspect that something was not kosher with the Johnsons. They obtained a warrant to search the house, but found nothing.

A night or two later, while William Johnson was asleep, John Johnson slipped down to the beach and provided the money with a new hiding place. A few days later, when William and John went to dig up the money to divide it, and found it gone, William became furious and accused his brother of trying to cheat him of his share. When John denied that he had removed the money, William went to the authorities and told them that his brother had hidden the coins. John was arrested, but released for lack of evidence. William moved out of the house and never spoke to John and his family again.

About this time, a severe storm lashed the Coney Island shore, eroding some of the beaches, and washing away a section of Pelican Island. It also washed ashore a lot of debris, along with some Mexican coins. An unofficial holiday was declared in Coney Island and Sheepshead Bay to permit their residents to go treasure hunting for pirate gold and silver being found at, and near, Manhattan Beach. It was assumed that this was the money John Johnson had concealed from his brother, and that the storm waters had washed away the hiding place and scattered the coins along the shore. John Johnson's demeanor seemed to bear this out, as he appeared dejected for a long time thereafter. It was true that his cache had ended up under water, but the coins had remained in the chest. The coins being washed ashore were from the bags that had been thrown overboard by the mutineers to lighten their water-logged rowboat.

The trial of the mutineers was held in March of 1831. Actually, there was little evidence against the three surviving mutineers. It was Brownrigg's word against theirs, that is, until Dawes decided to confess, and to testify against Gibbs and Wansley, who were found guilty of murder on the high seas, sentenced to death, and hanged on a gallows on Bedloe's (Liberty) Island, on April 22, 1831.

In 1875, long after all the principals involved in this affair had gone to their just rewards, John Johnson's son, a fisherman, was plying his trade in the waters where a section of Pelican Beach had been, when he was caught in a sudden storm. He was able to get his boat to safety, but lost an anchor. By the following morning the storm had abated, and he set about trying to retrieve his anchor by the use of a grappling hook. He caught something heavy and lifted it on board. It was an open chest partly filled with sand, which, upon being removed, revealed many gold and silver coins. The gold ones, which predominated, were in good condition, but the silver were badly corroded. Johnson reported his find to the authorities, but though they were Mexican coins, there was no way of establishing that the coins had come from the Vineyard, so Johnson was allowed to keep what he had found, which was valued at about $4,500. Thus, he had received a belated inheritance of his father's ill-gotten gains.

As with all good pirate tales, there must be a moral somewhere in this story. Perhaps it is that honesty is the best policy. Or, perhaps it is that if you have to steal, then steal from robbers, but definitely don't cheat your own brother of his share of the swag!

This entertaining article was written by the late Manny Teitelman for his unpublished book, "Coney Island, Last Stop!"

Published under exclusive copyright license, 2016. All rights reserved.

While at sea, Wansley, the ship's cook and steward, somehow found out about the money. He then plotted with multiple crew members - Henry Atwill, Aaron Church, Robert Dawes, and Charles Gibbs - to kill the captain and mate, and steal the money. Two other members of the crew, John Brownrigg and James Talbot, knew nothing of what was planned.

Shortly after midnight, when the ship was off Cape Hatteras, Wansley bludgeoned Captain William Thornby to death with a pump-brake, while the other mutineers hunted down and beat the mate, Mr. Roberts. Both Thornby and Roberts were then thrown overboard. Roberts was still alive at the time and tried to swim alongside the ship, pleading for his life, to no avail.

Brownrigg and Talbot, terrified by what they had seen, drew their knives for protection and fled aloft into the riggings. They were urged by the mutineers to come down and join them in sharing the treasure. Assured that they could keep their weapons, the two had no alternative but to comply.

The mutineers then set course for New York, bypassing the mouth of the Delaware River leading up to Philadelphia.

When they were off Southampton, Long Island, they decided to scuttle the ship. Brownrigg, Dawes, Gibbs, and Wansley got into the larger of the ship's two lifeboats with a chest containing $31,000; Atwill, Church, and Talbot got into the other rowboat with the remaining $23,000.

Just as the Vineyard was disappearing below the surface of the water, a gale blew up from the east, driving the lifeboats westward. They couldn't land in the wild surf, and were driven by wind and tide past several inlets.

Making for Rockaway Inlet, the smaller boat capsized, drowning its occupants. The other boat was taking on water faster than it could be bailed out. In a panic, the four aboard began to throw bags of coins into the sea to lighten the craft.

Finally, they reached Pelican Island, and got ashore. This island, now under water, was between Barren Island and Manhattan Beach, and had narrow channels between both. The channel at the Barren Island side was fordable at low tide.

There was a house on Barren Island occupied by John Johnson, his wife and children, and his brother, William. The mutineers, soaked and freezing, decided to bury the loot, now down to $5,000, and seek shelter in the house. They told the Johnsons that their captain, mate, and three members of the crew had been washed overboard in a storm that sank their ship. John Johnson offered them food and lodging for the night.

When the others were asleep, Brownrigg awakened John and William Johnson, revealed what had actually occurred, and told them where the money had been buried. John said that he and William would row the four of them to Sheepshead Bay in the morning, and that Brownrigg should tell the police there what had happened. The plan of the pirates was to hire a rig at Sheepshead Bay, return to Pelican Island for the money, row back to Sheepshead Bay, and drive to the city.

The next morning, the Johnsons rowed the four to Sheepshead Bay, left them there, rowed back to Pelican Island, dug up the money, and buried it elsewhere.

Meanwhile, Brownrigg was informing the police of the murders he had witnessed, and told of the buried money. The three accused killers were sent to a jail in Flatbush, while the police brought Brownrigg to the buried treasure, only to find it missing.

Further questioning of Brownrigg by the authorities made them suspect that something was not kosher with the Johnsons. They obtained a warrant to search the house, but found nothing.

A night or two later, while William Johnson was asleep, John Johnson slipped down to the beach and provided the money with a new hiding place. A few days later, when William and John went to dig up the money to divide it, and found it gone, William became furious and accused his brother of trying to cheat him of his share. When John denied that he had removed the money, William went to the authorities and told them that his brother had hidden the coins. John was arrested, but released for lack of evidence. William moved out of the house and never spoke to John and his family again.

About this time, a severe storm lashed the Coney Island shore, eroding some of the beaches, and washing away a section of Pelican Island. It also washed ashore a lot of debris, along with some Mexican coins. An unofficial holiday was declared in Coney Island and Sheepshead Bay to permit their residents to go treasure hunting for pirate gold and silver being found at, and near, Manhattan Beach. It was assumed that this was the money John Johnson had concealed from his brother, and that the storm waters had washed away the hiding place and scattered the coins along the shore. John Johnson's demeanor seemed to bear this out, as he appeared dejected for a long time thereafter. It was true that his cache had ended up under water, but the coins had remained in the chest. The coins being washed ashore were from the bags that had been thrown overboard by the mutineers to lighten their water-logged rowboat.

The trial of the mutineers was held in March of 1831. Actually, there was little evidence against the three surviving mutineers. It was Brownrigg's word against theirs, that is, until Dawes decided to confess, and to testify against Gibbs and Wansley, who were found guilty of murder on the high seas, sentenced to death, and hanged on a gallows on Bedloe's (Liberty) Island, on April 22, 1831.

In 1875, long after all the principals involved in this affair had gone to their just rewards, John Johnson's son, a fisherman, was plying his trade in the waters where a section of Pelican Beach had been, when he was caught in a sudden storm. He was able to get his boat to safety, but lost an anchor. By the following morning the storm had abated, and he set about trying to retrieve his anchor by the use of a grappling hook. He caught something heavy and lifted it on board. It was an open chest partly filled with sand, which, upon being removed, revealed many gold and silver coins. The gold ones, which predominated, were in good condition, but the silver were badly corroded. Johnson reported his find to the authorities, but though they were Mexican coins, there was no way of establishing that the coins had come from the Vineyard, so Johnson was allowed to keep what he had found, which was valued at about $4,500. Thus, he had received a belated inheritance of his father's ill-gotten gains.

As with all good pirate tales, there must be a moral somewhere in this story. Perhaps it is that honesty is the best policy. Or, perhaps it is that if you have to steal, then steal from robbers, but definitely don't cheat your own brother of his share of the swag!

This entertaining article was written by the late Manny Teitelman for his unpublished book, "Coney Island, Last Stop!"

Published under exclusive copyright license, 2016. All rights reserved.

Return to Coney Island History Homepage