Coney Island History: The Story of William Reynolds and Dreamland

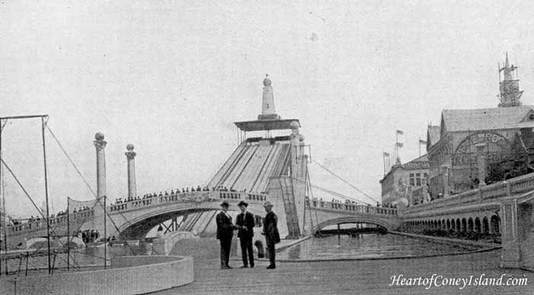

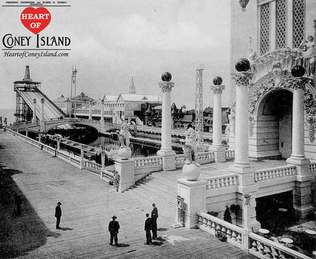

Dreamland, 1905 (Library of Congress)

Dreamland, 1905 (Library of Congress)

This fourth and final article on Coney Island's iconic amusement parks is the story of Dreamland. Prior articles cover Sea Lion Park, Steeplechase Park, and Luna Park.

Dreamland ranks alongside Luna Park and Disney World as one of the greatest amusement parks that the world has ever known. Dreamland's majestic tower dominated Coney Island's skyline from the park's opening in 1904 until its fiery demise in 1911. During those seven years, Dreamland and neighboring Luna Park engaged in a fierce battle for supremacy not just of Coney Island, but of the broader world of entertainment at the time. This period marks the rise and fall of both parks and defines the golden age of the amusement park.

Dreamland's story centers on the vision and ambition of its rather wily founder, William Reynolds, who embarked on quest to eclipse Luna Park just months after Luna had opened. Reynolds designed Dreamland specifically to compete with Luna Park and spared no expense, taking advantage of the amusement park investment craze that was in full swing globally following Luna Park's success. Investors poured millions of dollars into Dreamland. Reynolds initially also reinvested all of the park's receipts believing that Dreamland's triumph over Luna Park was just one more hit attraction away. Dreamland copied Luna's most popular rides, purchased rights to the most popular attractions exhibited at world's fairs, and hired away some of Luna's star performers. Reynolds even offered renowned Broadway stars a cut of the popcorn and peanut sales if they agreed to walk around Dreamland daily. The two great parks would remain locked in a battle in which a clear winner never emerged.

The article that follows is a comprehensive history of Dreamland. It is based on months of research and relies on primary sources including newspapers, court records, postcards and park ephemera. Perhaps the most interesting question the article poses is whether Reynolds' financial motivations contributed to the spectacular fire that eventually consumed Dreamland.

Dreamland ranks alongside Luna Park and Disney World as one of the greatest amusement parks that the world has ever known. Dreamland's majestic tower dominated Coney Island's skyline from the park's opening in 1904 until its fiery demise in 1911. During those seven years, Dreamland and neighboring Luna Park engaged in a fierce battle for supremacy not just of Coney Island, but of the broader world of entertainment at the time. This period marks the rise and fall of both parks and defines the golden age of the amusement park.

Dreamland's story centers on the vision and ambition of its rather wily founder, William Reynolds, who embarked on quest to eclipse Luna Park just months after Luna had opened. Reynolds designed Dreamland specifically to compete with Luna Park and spared no expense, taking advantage of the amusement park investment craze that was in full swing globally following Luna Park's success. Investors poured millions of dollars into Dreamland. Reynolds initially also reinvested all of the park's receipts believing that Dreamland's triumph over Luna Park was just one more hit attraction away. Dreamland copied Luna's most popular rides, purchased rights to the most popular attractions exhibited at world's fairs, and hired away some of Luna's star performers. Reynolds even offered renowned Broadway stars a cut of the popcorn and peanut sales if they agreed to walk around Dreamland daily. The two great parks would remain locked in a battle in which a clear winner never emerged.

The article that follows is a comprehensive history of Dreamland. It is based on months of research and relies on primary sources including newspapers, court records, postcards and park ephemera. Perhaps the most interesting question the article poses is whether Reynolds' financial motivations contributed to the spectacular fire that eventually consumed Dreamland.

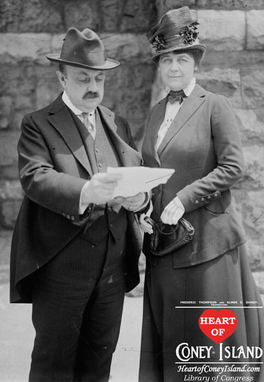

Dreamland's wily founder, William Reynolds, and wife, c. 1917

Dreamland's wily founder, William Reynolds, and wife, c. 1917

William Reynolds and Dreamland’s Origins as Wonderland (May – July, 1903)

The story of Dreamland - or Wonderland, its original name - begins in the summer of 1903, just a few months after Luna Park opened along Surf Avenue in West Brighton, Coney Island. Luna Park had transformed both Coney Island and the entire entertainment world almost overnight, making its founders, Thompson and Dundy, wealthy celebrities in the process. Luna Park was so profitable that Thompson and Dundy were able to repay all of their park loans by around July of 1903, just seven weeks after opening. And soon - though not quite yet - the pair also would expand into theatrical productions and open the renowned Hippodrome theater in Manhattan.

The excitement and potential business opportunity at West Brighton quickly caught the attention of Brooklyn businessman William H. Reynolds. Reynolds was a successful large-scale real estate developer who had developed much of Brooklyn’s Prospect Heights and Borough Park neighborhoods in the late 1890s. Luna Park's crowds were a boon for all West Brighton businesses, and Reynolds noted that the area's real estate was appreciating rapidly. Until recently, West Brighton had been regarded as the obstreperous stepchild of Coney Island’s more upscale Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach. Almost overnight, commercial properties in West Brighton were renting for more per square foot than almost anywhere else in Brooklyn. This was remarkable considering that the Coney Island business season lasted only four or five months.

Reynolds went to work figuring out how to create an amusement park of his own. Even if the park did not work out, investing in land at Coney Island still seemed like a profitable idea. Reynolds was uniquely positioned to undertake the challenge. In addition to being well-capitalized, Reynolds also knew how to expertly navigate New York City’s political arena. He had represented Brooklyn in the New York State Senate for the 1894 term and still had many contacts throughout City Hall. Over the years, Reynolds also developed a reputation for being quite willing to grease palms and to take some legal liberties to achieve his objectives.

Reynolds and the McKane Parcels Auction (July 1903)

The biggest obstacle to Reynolds' vision was finding a plot of land large enough for a full-scale park. Steeplechase and Luna Park occupied the only two large and contiguous lots of land in West Brighton. Reynolds began devising a plan to connect various disparate parcels of land.

Rather conveniently, but perhaps unsurprisingly given Reynolds' political connections, the sheriff’s office held a public auction on Wednesday, July 15th, for two adjacent West Brighton waterfront parcels totaling approximately six acres. The land had been seized to cover unpaid taxes of the estate of the John Y. McKane, the late corrupt political boss of Coney Island. These prime parcels had 262 feet of combined Surf Avenue frontage and each extended all the way down to the ocean, between 850 and 1,000 feet from Surf Avenue. The only problem was that a public city street, West 8th, separated the parcels. Together, they could form the core of a functional park, but separately, they were too small.

Developers regarded the West 8th Street issue either as insurmountable or too risky, and the auction was somewhat muted versus Reynolds' expectations. The lots nonetheless fetched a pretty penny given the West Brighton hype, selling for a combined total of $447,500. Local real estate agents said the parcels were worth in total at least $500,000 in total. Reynolds and other developers were outbid on both lots, with one lot going to a Mrs. C.L. Turnbull of Borough Park, and the other to a P.I. Thompson of the well-known real estate company Realty Buyers.

Two days after the auction, Reynolds surprised everyone by revealing that both winning bidders had actually been working for him. Realizing that bidding aggressively would tip other major developers as to his potential plans and that they could bid him up out of spite, Reynolds had feigned disinterest because of the West 8th Street issue. Secretly, however, he had a plan for joining them. Reynolds reportedly was prepared to pay over $500,000 for the lots and thought he had gotten a good deal. Years later, however, Reynolds testified that the purchase price had been 'exorbitant' in an attempt to minimize his real estate tax assessment. Reynolds was not the kind of man to let facts or honesty interfere with profits.

The story of Dreamland - or Wonderland, its original name - begins in the summer of 1903, just a few months after Luna Park opened along Surf Avenue in West Brighton, Coney Island. Luna Park had transformed both Coney Island and the entire entertainment world almost overnight, making its founders, Thompson and Dundy, wealthy celebrities in the process. Luna Park was so profitable that Thompson and Dundy were able to repay all of their park loans by around July of 1903, just seven weeks after opening. And soon - though not quite yet - the pair also would expand into theatrical productions and open the renowned Hippodrome theater in Manhattan.

The excitement and potential business opportunity at West Brighton quickly caught the attention of Brooklyn businessman William H. Reynolds. Reynolds was a successful large-scale real estate developer who had developed much of Brooklyn’s Prospect Heights and Borough Park neighborhoods in the late 1890s. Luna Park's crowds were a boon for all West Brighton businesses, and Reynolds noted that the area's real estate was appreciating rapidly. Until recently, West Brighton had been regarded as the obstreperous stepchild of Coney Island’s more upscale Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach. Almost overnight, commercial properties in West Brighton were renting for more per square foot than almost anywhere else in Brooklyn. This was remarkable considering that the Coney Island business season lasted only four or five months.

Reynolds went to work figuring out how to create an amusement park of his own. Even if the park did not work out, investing in land at Coney Island still seemed like a profitable idea. Reynolds was uniquely positioned to undertake the challenge. In addition to being well-capitalized, Reynolds also knew how to expertly navigate New York City’s political arena. He had represented Brooklyn in the New York State Senate for the 1894 term and still had many contacts throughout City Hall. Over the years, Reynolds also developed a reputation for being quite willing to grease palms and to take some legal liberties to achieve his objectives.

Reynolds and the McKane Parcels Auction (July 1903)

The biggest obstacle to Reynolds' vision was finding a plot of land large enough for a full-scale park. Steeplechase and Luna Park occupied the only two large and contiguous lots of land in West Brighton. Reynolds began devising a plan to connect various disparate parcels of land.

Rather conveniently, but perhaps unsurprisingly given Reynolds' political connections, the sheriff’s office held a public auction on Wednesday, July 15th, for two adjacent West Brighton waterfront parcels totaling approximately six acres. The land had been seized to cover unpaid taxes of the estate of the John Y. McKane, the late corrupt political boss of Coney Island. These prime parcels had 262 feet of combined Surf Avenue frontage and each extended all the way down to the ocean, between 850 and 1,000 feet from Surf Avenue. The only problem was that a public city street, West 8th, separated the parcels. Together, they could form the core of a functional park, but separately, they were too small.

Developers regarded the West 8th Street issue either as insurmountable or too risky, and the auction was somewhat muted versus Reynolds' expectations. The lots nonetheless fetched a pretty penny given the West Brighton hype, selling for a combined total of $447,500. Local real estate agents said the parcels were worth in total at least $500,000 in total. Reynolds and other developers were outbid on both lots, with one lot going to a Mrs. C.L. Turnbull of Borough Park, and the other to a P.I. Thompson of the well-known real estate company Realty Buyers.

Two days after the auction, Reynolds surprised everyone by revealing that both winning bidders had actually been working for him. Realizing that bidding aggressively would tip other major developers as to his potential plans and that they could bid him up out of spite, Reynolds had feigned disinterest because of the West 8th Street issue. Secretly, however, he had a plan for joining them. Reynolds reportedly was prepared to pay over $500,000 for the lots and thought he had gotten a good deal. Years later, however, Reynolds testified that the purchase price had been 'exorbitant' in an attempt to minimize his real estate tax assessment. Reynolds was not the kind of man to let facts or honesty interfere with profits.

Reynolds Describes his initial Vision for Dreamland and Raises Capital (July – September, 1903)

Reynolds gave details shortly post-auction on his vision for a pleasure park. The park would be called the Hippodrome and be modeled off of two of London’s leading pleasure parks, the Crystal Gardens and the London Hippodrome. In addition to typical rides, the park would provide ocean bathing facilities and showcase the world’s best Shoot the Chutes, which would extend into the ocean 500 feet beyond the high water mark. Wanting to install many lights and knowing he would soon need to negotiate rates for a large amount of electricity, Reynolds also postured that he would build a massive power plant on the grounds to compete with Edison Electric to power all of West Brighton. The degree of specificity Reynolds provided in the interview supports the theory that Reynolds had influenced the timing of the auction, using his political connections to delay it until he was well-prepared.

Over the next month, Reynolds drafted a stock prospectus to raise an estimated $1 million in total for the park’s construction. The Wonderland Company was incorporated on August 18th, 1903, with $1.2 million in capital. Reynolds sold the stock in relatively small lots under the guise of wanting to allow for participation from local small business owners, claiming they were adversely affected by Luna Park’s opening. The roster of investors unsurprisingly ended up including many local politicians, government officials and powerful Coney Island businessmen. These were exactly the people who could help Reynolds solve his West 8th Street issue.

Reynolds vehemently denied initial rumors that Brooklyn boss Senator Patrick McCarren and former senator Anthony N. Brady were outright partners in his venture. He did, however, point out to reporters that McCarren and Brady could submit orders to purchase stock, like anyone else, if they so desired. When Dreamland burned in 1911, Dreamland's then-current investor roster included G.F. Dobson, the managing editor of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle newspaper, which unsurprisingly frequently wrote glowing reviews of Dreamland; William Engeman, the Brighton Beach impresario; Timothy 'Big Tim' Sullivan, Tammany Hall’s notorious politician; and a certain Arnold Rothstein, described as a ‘sporting man’ and likely the famous New York mafia associate. It is likely that most of these, perhaps all except for Rothstein, invested in Dreamland at its inception in 1903.

Reynolds Tackles the Key Issue of Rezoning West 8th Street (September 1903)

Reynolds and his politically-connected investor group quickly got to work on resolving Dreamland’s West 8th Street problem to clear the way for construction. Under the terms of the land auction, Reynolds was scheduled to take title to the lots on Thursday, September 24th, the day after the official close of Coney Island’s 1903 season.

The Bay Ridge Local Board met on the season’s last day. The timing was once again almost certainly due to Reynolds' political influence. Reynolds personally attended and argued that the business benefits to the community from another amusement park would be significant and further West Brighton’s transformation into an area of ‘moral character’. The Board voted to close West 8th Street between Surf Avenue and the ocean on that basis, noting that the street had never really been actively used. The Board either ceded effective control and use of the land to Reynolds, or perhaps even handed the property over to Reynolds free of charge.

Reynolds' newly-connected properties had just doubled in value overnight through this political maneuver. He was now ready to build Dreamland. Years later, it would be discovered that Dreamland had been consuming millions of gallons of unmetered water from the fire hydrant lines under West 8th Street. West Brighton’s character may have become more moral, but Reynolds’ character decidedly had not. John McKane’s estate certainly had found a fitting successor.

Reynolds busied himself during September of 1903 securing additional loans ahead of construction. General financial conditions were disagreeable because of the Panic of 1903. Many stocks had all but ceased trading, loans were hard to come by and few people save Bet-a-Million Gates were buying securities. Dreamland proved irresistible to investors, however. Luna Park’s success the prior season had created a global investment frenzy for anything relating to amusement parks. Coupled with Dreamland’s political and business connections, an investment in Dreamland seem like a sure bet.

Dreamland Tower from the Chutes

Dreamland Tower from the Chutes

Dreamland's Design and Architecture (July – October 1903)

Overall, Dreamland’s design would have to be more compact than Luna Park’s. Dreamland’s acreage consisted of the two McKane lots totaling 6 acres, ‘a couple’ of additional adjoining acres leased mid-December of 1903 from a James Doyle, and additional acreage purchased for $225,000 sometime during 1904. It appears that Dreamland sat on a little over 14 acres versus Luna Park’s 22 acres. Dreamland likely was embellishing when it consistently advertised a full 39 acres in newspapers, including in a full-page ad featured in the New York Herald on May 29, 1904.

The architecture firm of Kirby, Petit & Green designed Dreamland’s grounds and buildings. John Petit arrived at an interesting idea to compete with Luna Park’s whimsical architecture. He likely noted that the popular world’s fairs, starting with the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, were designed in two sections: a refined ‘White City’ with graceful neoclassical buildings, and a raucous amusements midway. The public liked the elegance of ‘White City’ but found its museum-like exhibits comparatively boring. After a brief tour, people would inevitably head to the midway. Petit combined the best elements of each in Dreamland to create what might be called a 'Midway in White City'.

Replicating the basic geometric layout of the world’s fairs, Petit designed Dreamland around a central rectangular court flanked on three sides by buildings housing attractions. On the fourth side stood a majestic tower that closely resembled the Giralda Tower of Seville, Spain. Many of Dreamland’s attractions involved simulated travels to foreign countries, and Petit designed the buildings to replicate relevant foreign palaces or famous landmarks. Petit chose the more refined color scheme of white with gold accents for Dreamland, in contrast to Luna Park's more playful white and Turkish red palette. Staff, a malleable, syrupy form of cement that could be cast and hardened into any shape, was used as the primary building material, as it had been at many of the recent world’s fairs. The overall result was an amusement park whose elegance was on par with the greatest of these fairs.

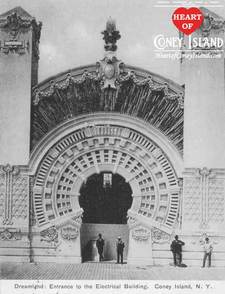

Electrical Building c. 1905

Electrical Building c. 1905

The Construction and Renaming of Dreamland (October 1903 – May 1904)

Construction began in October. Reynolds had originally projected Dreamland to open by mid-August of 1904. Now, he decided to accelerate the schedule, probably to capture revenues from the full 1904 season. Time was of essence because there were only seven and one-half months until opening day in early May.

Reynolds worked his construction crews in shifts 24 hours a day, initially employing 300 to 400 workers per shift. By March, he increased to 500 workers per shift as time-consuming plastering and cosmetic touches were being made. The political bosses backing Dreamland, both Republican and Democrat, agreed to use an entirely non-union crews because union work rules would not allow construction to finish in time. Management also was not particularly generous, refusing to pay workers for time off on Washington’s Birthday, a national holiday. When over 800 workers went on strike the day after, on Tuesday, February 23rd, Reynolds’ superintendent fired all of the strikers and replaced them the next day. Hard-nosed tactics would become more challenging to implement in the coming months because of a shortage of skilled labor at Coney Island. Not only was Dreamland under construction, but changes being made at Luna Park and a massive fire had wiped out (or ‘cleansed’, as the more Puritanical observers at the time described it) most of the Bowery. By March, Dreamland was resorting to advertising in local newspapers for plasterers, casters and workers who could sculpt with staff. Work was still proceeding feverishly the day before opening.

Reynolds also retracted his bluff of going into the power generation business to compete with Edison Electric. Instead, Dreamland awarded Edison Electric the largest single contract for electricity in the United States at the time, and according to Edison Electric, likely the largest in the world. Dreamland contracted more power than all of Coney Island combined the prior year, even including Luna Park. Edison Electric made extensive additions to its power plant and also built a smaller plant within Dreamland to transform current.

As opening day approached, Reynolds and his team decided that the name Dreamland was more marketable than Wonderland. The Dreamland Corporation was officially born on March 3rd, 1904, and combined with the Wonderland Company on March 12th.

Construction began in October. Reynolds had originally projected Dreamland to open by mid-August of 1904. Now, he decided to accelerate the schedule, probably to capture revenues from the full 1904 season. Time was of essence because there were only seven and one-half months until opening day in early May.

Reynolds worked his construction crews in shifts 24 hours a day, initially employing 300 to 400 workers per shift. By March, he increased to 500 workers per shift as time-consuming plastering and cosmetic touches were being made. The political bosses backing Dreamland, both Republican and Democrat, agreed to use an entirely non-union crews because union work rules would not allow construction to finish in time. Management also was not particularly generous, refusing to pay workers for time off on Washington’s Birthday, a national holiday. When over 800 workers went on strike the day after, on Tuesday, February 23rd, Reynolds’ superintendent fired all of the strikers and replaced them the next day. Hard-nosed tactics would become more challenging to implement in the coming months because of a shortage of skilled labor at Coney Island. Not only was Dreamland under construction, but changes being made at Luna Park and a massive fire had wiped out (or ‘cleansed’, as the more Puritanical observers at the time described it) most of the Bowery. By March, Dreamland was resorting to advertising in local newspapers for plasterers, casters and workers who could sculpt with staff. Work was still proceeding feverishly the day before opening.

Reynolds also retracted his bluff of going into the power generation business to compete with Edison Electric. Instead, Dreamland awarded Edison Electric the largest single contract for electricity in the United States at the time, and according to Edison Electric, likely the largest in the world. Dreamland contracted more power than all of Coney Island combined the prior year, even including Luna Park. Edison Electric made extensive additions to its power plant and also built a smaller plant within Dreamland to transform current.

As opening day approached, Reynolds and his team decided that the name Dreamland was more marketable than Wonderland. The Dreamland Corporation was officially born on March 3rd, 1904, and combined with the Wonderland Company on March 12th.

Gumpertz's Giant and Dwarf

Gumpertz's Giant and Dwarf

Reynolds' Strategy for Taking on Luna Park

Reynolds' strategy heading into his showdown with Thompson and Dundy of Luna Park was so perfectly straightforward and logical that it could serve as a business school case study. Dreamland's strategic advantages were that it was better capitalized, that it knew what attractions had worked well (and which had not) during Luna Park's first season, and that it stood on a smaller but superior plot of land with its own steamer pier and oceanfront bathing access. Reynolds planned on extracting maximum value from each of these advantages.

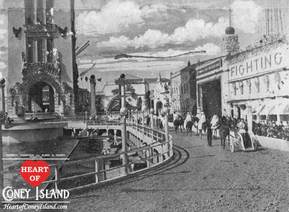

First, Dreamland would match all of Luna Park's popular attractions so that customers would have no tangible reason to prefer Luna over Dreamland. Dreamland made its own version of almost every successful ride that Luna Park had offered the prior season. When possible, the rides were improved in some way. To Reynolds, this often simply meant making things bigger. Dreamland would have more lights (one million versus 250,000), a taller tower (375 feet tall versus 200 feet tall), a bigger ballroom, more infant incubators and a bigger Shoot the Chutes than Luna Park (two ramps versus one). Dreamland would have Fighting the Flames instead of Fire and Flames, Submarine Boat Moccasin instead of 20,000 Leagues under the Sea, an animal show led by Frank Bostock instead of Carl Hagenbeck, and so on. This might not have been particularly creative, but it was rather logical.

Second, Dreamland would add some unique attractions that would in theory make customers prefer it to Luna Park, all else being equal. Dreamland would have unique engineering marvels such as the Leapfrog Railway and various types of airplane rides that appealed to the public’s fascination with aviation. Famous Broadway actors and actresses like Marie Dressler would walk the park every day in exchange for a cut of the food or souvenir sales they were overseeing.

Third, Dreamland would advertise its beachfront access and bathing facilities. These had the potential to be a significant draw because much of West Brighton’s beach was privately owned at the time and accessible only through bath houses. For example, Luna Park’s customers would have to exit Luna if they wanted to go bathing, while Dreamland could keep its customers within the park, much like the strategy used by modern-day, all-inclusive resorts. Dreamland would also establish its own fleet of steamships to bring customers directly to Dreamland's waterfront entrance at Dreamland Pier.

Last but not least, Reynolds hired Sam Gumpertz as Dreamland’s general manager for his amusement industry expertise. Gumpertz was a well-known showman who wore perfectly round spectacles and had a successful track record of managing circuses and sideshows. He had much of the same fairground midway experience as Thompson and Dundy. Gumpertz saw that curious crowds would pay to see foreign or unusual people, places and animals. Gumpertz immediately lived up to his reputation by creating one of Dreamland’s most successful and imaginative attractions, Midget City. Gumpertz's creative flair was a much-needed complement to Reynolds' sensible but rather businesslike take on things.

Reynolds' strategy heading into his showdown with Thompson and Dundy of Luna Park was so perfectly straightforward and logical that it could serve as a business school case study. Dreamland's strategic advantages were that it was better capitalized, that it knew what attractions had worked well (and which had not) during Luna Park's first season, and that it stood on a smaller but superior plot of land with its own steamer pier and oceanfront bathing access. Reynolds planned on extracting maximum value from each of these advantages.

First, Dreamland would match all of Luna Park's popular attractions so that customers would have no tangible reason to prefer Luna over Dreamland. Dreamland made its own version of almost every successful ride that Luna Park had offered the prior season. When possible, the rides were improved in some way. To Reynolds, this often simply meant making things bigger. Dreamland would have more lights (one million versus 250,000), a taller tower (375 feet tall versus 200 feet tall), a bigger ballroom, more infant incubators and a bigger Shoot the Chutes than Luna Park (two ramps versus one). Dreamland would have Fighting the Flames instead of Fire and Flames, Submarine Boat Moccasin instead of 20,000 Leagues under the Sea, an animal show led by Frank Bostock instead of Carl Hagenbeck, and so on. This might not have been particularly creative, but it was rather logical.

Second, Dreamland would add some unique attractions that would in theory make customers prefer it to Luna Park, all else being equal. Dreamland would have unique engineering marvels such as the Leapfrog Railway and various types of airplane rides that appealed to the public’s fascination with aviation. Famous Broadway actors and actresses like Marie Dressler would walk the park every day in exchange for a cut of the food or souvenir sales they were overseeing.

Third, Dreamland would advertise its beachfront access and bathing facilities. These had the potential to be a significant draw because much of West Brighton’s beach was privately owned at the time and accessible only through bath houses. For example, Luna Park’s customers would have to exit Luna if they wanted to go bathing, while Dreamland could keep its customers within the park, much like the strategy used by modern-day, all-inclusive resorts. Dreamland would also establish its own fleet of steamships to bring customers directly to Dreamland's waterfront entrance at Dreamland Pier.

Last but not least, Reynolds hired Sam Gumpertz as Dreamland’s general manager for his amusement industry expertise. Gumpertz was a well-known showman who wore perfectly round spectacles and had a successful track record of managing circuses and sideshows. He had much of the same fairground midway experience as Thompson and Dundy. Gumpertz saw that curious crowds would pay to see foreign or unusual people, places and animals. Gumpertz immediately lived up to his reputation by creating one of Dreamland’s most successful and imaginative attractions, Midget City. Gumpertz's creative flair was a much-needed complement to Reynolds' sensible but rather businesslike take on things.

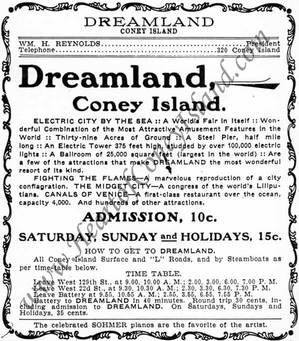

Dreamland Advertisement for its Inaugural Season, 1904

Dreamland Advertisement for its Inaugural Season, 1904

The Details of Dreamland's Immense Cost

The downside of Reynolds’ strategy was its astonishing cost, much of which was borrowed. Thompson and Dundy had advertised that Luna Park cost $1.5 million to build; Reynolds was advertising $3.5 million for Dreamland. Both figures likely were inflated for marketing effect and most likely included the cost of purchasing the underlying land. Nonetheless, records show Dreamland had outstanding debts totaling $1.9 million ahead of opening day. Allowing for additional equity capital, which is difficult to pinpoint based on available records, means that Dreamland's advertised figure may not have been vastly exaggerated after all.

Recouping Dreamland’s cost and producing an acceptable rate of return for shareholders required making rather optimistic operating assumptions. Luna Park had reportedly cleared $500,000 in pre-tax profits during its inaugural 1903 season. Luna Park had benefited from the novelty factor, favorable weather, and nearly monopolistic business conditions as Steeplechase Park had not put up much of a fight. The trouble was that Dreamland's capital base was double that of Luna's, with Dreamland's debts alone exceeding Luna Park's entire invested capital. Even if every single customer deserted Luna Park for Dreamland, Dreamland likely would be unable to repay all of its debts during the first season, as Luna Park had done. This would require additional borrowing for the capital-intensive off-season as new attractions were added and existing ones updated ahead of the second season. Even if things worked out longer-term, Dreamland's shareholders should have expected their returns to be significantly lower and slower to come than those of Luna Park the prior year.

More realistically, the revenue base at West Brighton was likely to prove too small to profitably support two state-of-the-art parks with comparable rides and capital-intensive, hit-driven business models. For both Luna Park and Dreamland each to clear $500,000 in profits in 1904, overall amusement revenues at West Brighton would have to grow by $500,000 plus Dreamland’s fixed costs. This would certainly be a challenge for Dreamland, charging fifteen cents for park admission (ten cents on weekdays) and between ten cents and at most twenty-five cents for park attractions. If Luna Park and Dreamland split the existing market, neither would be profitable longer-term. Additionally, the comparatively-outdated Steeplechase Park had offered little competition but was unlikely to sit by idly for much longer without upgrading. Lastly, ongoing capital expenditures at both Luna Park and Dreamland would be high, as they had to compete for and license the latest attractions. Simply stated, Dreamland would have to draw away many of Luna Park’s customers while also hoping for overall market growth to make up for any customers that Luna Park retained.

Additionally, Dreamland faced significant ongoing annual interest payments. Reconciling the exact amount of debt and equity invested in Dreamland is complicated by Dreamland’s merger with Wonderland and inconsistencies in primary sources. What is clear is that Dreamland's $1.9 million in total debt consisted of a $400,000 mortgage at 5.5% interest, $750,000 in 10-year secured mortgage-and-income gold bonds at 6% interest, and $750,000 of unsecured gold bonds at 6% interest. Interest payments on the unsecured gold bonds contractually started on September 1906, suggesting that Reynolds understood cash flow might be tight. This meant that Dreamland would face annual interest payments totaling $67,000 ahead of September 1906 and $112,000 once the unsecured bonds kicked in thereafter. Dreamland’s mortgage likely amortized the principal as well, adding to cash payments. Against this backdrop, Thompson and Dundy had used Luna Park’s profits to repay all of their construction debts and were now entirely debt-free.

In terms of equity capital, Reynolds testified that half of Dreamland’s stock was given to the secured bond purchasers as a sweetener, with Reynolds receiving the other half in exchange for his ‘sweat equity’ in spearheading the project. Additional money appears to have been raised by Wonderland’s prior sales of stock or injected by Reynolds himself. It is unclear how this reconciles with Reynolds’ testimony, but Reynolds frequently took liberties under oath.

All in all, Dreamland’s strategy and its very survival centered on whether it could deliver an early-stage knock-out blow to Luna Park. As opening day approached, Reynolds sat on one side of Surf Avenue, and Thompson and Dundy on the other, both watching each other’s parks with nervous anticipation, bracing for the inevitable showdown.

Dreamland’s Opening Day (May 14, 1904)

Dreamland opened shortly before noon on Saturday, May 14, 1904. Unlike Luna Park’s carefully-planned lighting precisely at sunset the prior year, Dreamland simply got down to business. Doors were thrown open and admission tickets were sold for fifteen cents. Later that evening, cold and a thick fog kept the crowds away from Coney Island, and only a nominal crowd walked Dreamland’s promenades. Yet, the ballroom was crowded from afternoon late into the evening, and everyone agreed that it was the finest in Coney Island. Midget City, Dreamland’s version of Luna Park’s Fighting Flames and Bostock’s Circus also received glowing reviews. Many of the other attractions, including the Dreamland Tower observatory, were still under construction. Most would be finished by Memorial Day, then-known as Decoration Day.

Luna Park opened on the same day as Dreamland and also had multiple attractions still under construction. Thompson and Dundy had reinvested a substantial portion of their profits to maintain their leadership with respect to offering the latest attractions. Luna Park had no intention of going down without putting up a fight.

Visiting Dreamland in 1904: How You Would Have Traveled to Dreamland

In mid-summer of 1904, only the wealthy could make the journey to Coney Island in a car. The two primary options for everyone else coming from Manhattan or Brooklyn were railroad and steamship. Dreamland’s four entrances, two facing Surf Avenue and two intended for steamship passengers, made both easy options.

The downside of Reynolds’ strategy was its astonishing cost, much of which was borrowed. Thompson and Dundy had advertised that Luna Park cost $1.5 million to build; Reynolds was advertising $3.5 million for Dreamland. Both figures likely were inflated for marketing effect and most likely included the cost of purchasing the underlying land. Nonetheless, records show Dreamland had outstanding debts totaling $1.9 million ahead of opening day. Allowing for additional equity capital, which is difficult to pinpoint based on available records, means that Dreamland's advertised figure may not have been vastly exaggerated after all.

Recouping Dreamland’s cost and producing an acceptable rate of return for shareholders required making rather optimistic operating assumptions. Luna Park had reportedly cleared $500,000 in pre-tax profits during its inaugural 1903 season. Luna Park had benefited from the novelty factor, favorable weather, and nearly monopolistic business conditions as Steeplechase Park had not put up much of a fight. The trouble was that Dreamland's capital base was double that of Luna's, with Dreamland's debts alone exceeding Luna Park's entire invested capital. Even if every single customer deserted Luna Park for Dreamland, Dreamland likely would be unable to repay all of its debts during the first season, as Luna Park had done. This would require additional borrowing for the capital-intensive off-season as new attractions were added and existing ones updated ahead of the second season. Even if things worked out longer-term, Dreamland's shareholders should have expected their returns to be significantly lower and slower to come than those of Luna Park the prior year.

More realistically, the revenue base at West Brighton was likely to prove too small to profitably support two state-of-the-art parks with comparable rides and capital-intensive, hit-driven business models. For both Luna Park and Dreamland each to clear $500,000 in profits in 1904, overall amusement revenues at West Brighton would have to grow by $500,000 plus Dreamland’s fixed costs. This would certainly be a challenge for Dreamland, charging fifteen cents for park admission (ten cents on weekdays) and between ten cents and at most twenty-five cents for park attractions. If Luna Park and Dreamland split the existing market, neither would be profitable longer-term. Additionally, the comparatively-outdated Steeplechase Park had offered little competition but was unlikely to sit by idly for much longer without upgrading. Lastly, ongoing capital expenditures at both Luna Park and Dreamland would be high, as they had to compete for and license the latest attractions. Simply stated, Dreamland would have to draw away many of Luna Park’s customers while also hoping for overall market growth to make up for any customers that Luna Park retained.

Additionally, Dreamland faced significant ongoing annual interest payments. Reconciling the exact amount of debt and equity invested in Dreamland is complicated by Dreamland’s merger with Wonderland and inconsistencies in primary sources. What is clear is that Dreamland's $1.9 million in total debt consisted of a $400,000 mortgage at 5.5% interest, $750,000 in 10-year secured mortgage-and-income gold bonds at 6% interest, and $750,000 of unsecured gold bonds at 6% interest. Interest payments on the unsecured gold bonds contractually started on September 1906, suggesting that Reynolds understood cash flow might be tight. This meant that Dreamland would face annual interest payments totaling $67,000 ahead of September 1906 and $112,000 once the unsecured bonds kicked in thereafter. Dreamland’s mortgage likely amortized the principal as well, adding to cash payments. Against this backdrop, Thompson and Dundy had used Luna Park’s profits to repay all of their construction debts and were now entirely debt-free.

In terms of equity capital, Reynolds testified that half of Dreamland’s stock was given to the secured bond purchasers as a sweetener, with Reynolds receiving the other half in exchange for his ‘sweat equity’ in spearheading the project. Additional money appears to have been raised by Wonderland’s prior sales of stock or injected by Reynolds himself. It is unclear how this reconciles with Reynolds’ testimony, but Reynolds frequently took liberties under oath.

All in all, Dreamland’s strategy and its very survival centered on whether it could deliver an early-stage knock-out blow to Luna Park. As opening day approached, Reynolds sat on one side of Surf Avenue, and Thompson and Dundy on the other, both watching each other’s parks with nervous anticipation, bracing for the inevitable showdown.

Dreamland’s Opening Day (May 14, 1904)

Dreamland opened shortly before noon on Saturday, May 14, 1904. Unlike Luna Park’s carefully-planned lighting precisely at sunset the prior year, Dreamland simply got down to business. Doors were thrown open and admission tickets were sold for fifteen cents. Later that evening, cold and a thick fog kept the crowds away from Coney Island, and only a nominal crowd walked Dreamland’s promenades. Yet, the ballroom was crowded from afternoon late into the evening, and everyone agreed that it was the finest in Coney Island. Midget City, Dreamland’s version of Luna Park’s Fighting Flames and Bostock’s Circus also received glowing reviews. Many of the other attractions, including the Dreamland Tower observatory, were still under construction. Most would be finished by Memorial Day, then-known as Decoration Day.

Luna Park opened on the same day as Dreamland and also had multiple attractions still under construction. Thompson and Dundy had reinvested a substantial portion of their profits to maintain their leadership with respect to offering the latest attractions. Luna Park had no intention of going down without putting up a fight.

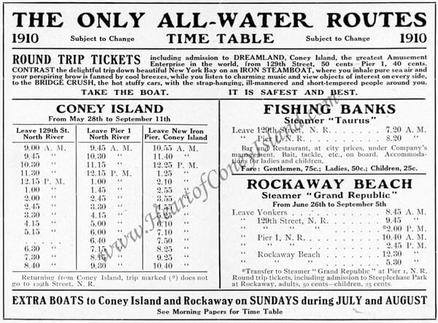

Visiting Dreamland in 1904: How You Would Have Traveled to Dreamland

In mid-summer of 1904, only the wealthy could make the journey to Coney Island in a car. The two primary options for everyone else coming from Manhattan or Brooklyn were railroad and steamship. Dreamland’s four entrances, two facing Surf Avenue and two intended for steamship passengers, made both easy options.

Railroad. The best bet for railroad travel was the popular Sea Beach Express route, one of the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company’s lines. The Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company has just completed a large capacity increase during the winter of 1903 for the expected crowds of the 1904 season. An express train from Park Row in lower Manhattan would cross the Brooklyn Bridge and arrive at Sea Beach Palace Station in Coney Island in just 32 minutes. Each express train had five cars, each carrying about 100 passengers comfortably, though more would inevitably crowd in. Passengers would walk east along Surf Avenue to Dreamland’s main entrance, which was adjacent to the where West 6th Street was in the days of Culver Plaza. The main entrance led directly into Dreamland's east promenade. A secondary entrance was located at Surf Avenue and West 8th Street. For the 1905 season, Dreamland’s main entrance would be reconstructed to incorporate the famous 30-foot tall, 100-ton topless statue of a female angel advertising Roltair’s Creation illusion.

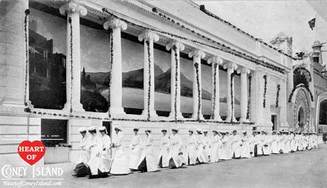

Steamship. There were two good 'steamer' options for traveling to Dreamland. The best option was to take one of Dreamland’s own four large side-wheel steamships directly to Dreamland Pier (the remodeled Old Iron Pier) from either 129th Street in Harlem, 23rd Street or Battery Park. A large bell would ring on Dreamland Pier when ships arrived. Passengers would walk on the lower level of the Dreamland Pier, which ran under the ballroom and restaurant, directly into Dreamland. Combined, the Dreamland Navigation Company’s steamboats carried 10,000 passengers at a time and each made four trips a day to Dreamland Pier. The second option was to take the Iron Steamboat Company’s steamers to New Iron Pier from either 129th Street Pier or Pier 1 at Brooklyn Bridge Park. Ships departed every half-hour starting at 9am, with the last regularly-scheduled ship return departing at 10:40pm. Passengers could ‘listen to charming music and view objects of interest on every side,’ and avoid the unpleasantness of the railroad’s ‘hot stuffy cars, with the strap-hanging, ill-mannered and short-tempered people’. Passengers entered Dreamland through a side entrance along the south side of the Canals of Venice attraction. The round-trip cost $0.40 and included admission to Dreamland. A third option was to travel to Coney Island on Steeplechase Park’s steamers, but they arrived all the way down at Steeplechase Pier.

Steamship. There were two good 'steamer' options for traveling to Dreamland. The best option was to take one of Dreamland’s own four large side-wheel steamships directly to Dreamland Pier (the remodeled Old Iron Pier) from either 129th Street in Harlem, 23rd Street or Battery Park. A large bell would ring on Dreamland Pier when ships arrived. Passengers would walk on the lower level of the Dreamland Pier, which ran under the ballroom and restaurant, directly into Dreamland. Combined, the Dreamland Navigation Company’s steamboats carried 10,000 passengers at a time and each made four trips a day to Dreamland Pier. The second option was to take the Iron Steamboat Company’s steamers to New Iron Pier from either 129th Street Pier or Pier 1 at Brooklyn Bridge Park. Ships departed every half-hour starting at 9am, with the last regularly-scheduled ship return departing at 10:40pm. Passengers could ‘listen to charming music and view objects of interest on every side,’ and avoid the unpleasantness of the railroad’s ‘hot stuffy cars, with the strap-hanging, ill-mannered and short-tempered people’. Passengers entered Dreamland through a side entrance along the south side of the Canals of Venice attraction. The round-trip cost $0.40 and included admission to Dreamland. A third option was to travel to Coney Island on Steeplechase Park’s steamers, but they arrived all the way down at Steeplechase Pier.

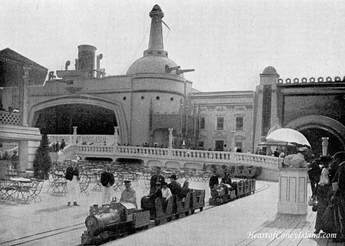

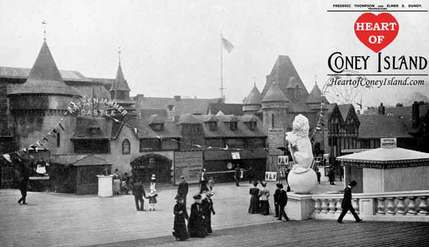

Dreamland's Midget City and its Katzenjammer Castle

Dreamland's Midget City and its Katzenjammer Castle

Visiting Dreamland in 1904: The Most Popular Attractions

Why would someone have wanted to go to Dreamland instead of Luna Park in 1904? Dreamland was a full-fledged amusement resort that had a private beach, every type of attraction and ride imaginable, a circus, a massive restaurant and a beautiful ballroom. The only thing it lacked was its own hotel, likely because it had to close at night for maintenance. The following were Dreamland’s top attractions, in approximate order of popularity.

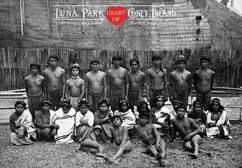

Midget City. Midget City and Bostock’s Animal Arena were the two most popular attractions at Dreamland in 1904. Gumpertz and the general public at the time were fascinated by people who were physically different in some way. After Dreamland burned years later, Gumpertz would go on to create the Dreamland Sideshow, a leading freak show of the era. For now, he contented himself with hiring a giant and dwarf to walk around the park together. The giant sold massive rings off of his fingers as mementos. Gumpertz also tried to hire Little Tich, a world-famous English midget performer who had toured in the United States in the late 1880s and later returned to Europe. Unable to convince Little Tich, Gumpertz turned to the equally world-famous General Tom Thumb. Together, they built a small city that served as a permanent residence at Dreamland for Tom Thumb, his wife, and several hundred other midgets.

Lilliputian Village, better known as Midget City, was a fully-functional miniature village modeled after a German town. The Lilliputians lived and slept there, and were so ‘busily engaged in many occupations and in such a natural way that the visitor is fain to forget himself in Coney Island and think himself a Gulliver in Lilliput.’ The city was complete with a tavern, restaurant, dark alleys that appealed to midget brigands, a theater, and a circus, everything perfectly scaled down to miniature size. It even had its own fire brigade, with a miniature steam-powered fire engine and two ponies to pull it. For children, it was like entering a perfectly-sized world; parents would frequently hit their heads or have trouble walking up several small-sized staircases, to the delight of the kids. Midget City was allocated a large amount of space at the southwest corner of Dreamland, near the entrance from Dreamland Pier. As one reviewer said, ‘This show cannot be overrated when one comes to speak of its unusual and attractive qualities.’

Why would someone have wanted to go to Dreamland instead of Luna Park in 1904? Dreamland was a full-fledged amusement resort that had a private beach, every type of attraction and ride imaginable, a circus, a massive restaurant and a beautiful ballroom. The only thing it lacked was its own hotel, likely because it had to close at night for maintenance. The following were Dreamland’s top attractions, in approximate order of popularity.

Midget City. Midget City and Bostock’s Animal Arena were the two most popular attractions at Dreamland in 1904. Gumpertz and the general public at the time were fascinated by people who were physically different in some way. After Dreamland burned years later, Gumpertz would go on to create the Dreamland Sideshow, a leading freak show of the era. For now, he contented himself with hiring a giant and dwarf to walk around the park together. The giant sold massive rings off of his fingers as mementos. Gumpertz also tried to hire Little Tich, a world-famous English midget performer who had toured in the United States in the late 1880s and later returned to Europe. Unable to convince Little Tich, Gumpertz turned to the equally world-famous General Tom Thumb. Together, they built a small city that served as a permanent residence at Dreamland for Tom Thumb, his wife, and several hundred other midgets.

Lilliputian Village, better known as Midget City, was a fully-functional miniature village modeled after a German town. The Lilliputians lived and slept there, and were so ‘busily engaged in many occupations and in such a natural way that the visitor is fain to forget himself in Coney Island and think himself a Gulliver in Lilliput.’ The city was complete with a tavern, restaurant, dark alleys that appealed to midget brigands, a theater, and a circus, everything perfectly scaled down to miniature size. It even had its own fire brigade, with a miniature steam-powered fire engine and two ponies to pull it. For children, it was like entering a perfectly-sized world; parents would frequently hit their heads or have trouble walking up several small-sized staircases, to the delight of the kids. Midget City was allocated a large amount of space at the southwest corner of Dreamland, near the entrance from Dreamland Pier. As one reviewer said, ‘This show cannot be overrated when one comes to speak of its unusual and attractive qualities.’

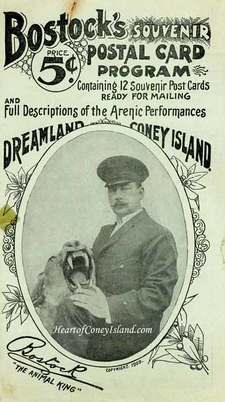

Bostock Arena Souvenir, Cover, 1909

Bostock Arena Souvenir, Cover, 1909

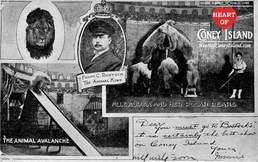

Bostock’s Animal Arena. Frank Bostock, the famous animal trainer, was hired to compete with Luna Park's Carl Hagenbeck. His acts performed in a specially-designed indoor circus located immediately to the right of Dreamland's main Surf Avenue entrance. Bostock’s was a perennial favorite. On Memorial Day alone of the following year, 1905, it had over 30,000 visitors, including almost 20,000 children.

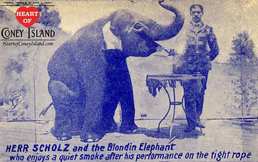

Bostock show spent the summers at Coney Island and the winters in Paris. A variety of animal trainers, each with their own animal act, worked independently under Bostock. Bostock supervised all of the acts during rehearsals to ensure they were entertaining, and was frequently in the audience during actual shows. Bostock’s trainers included Captain Jack Bonavita, who served as the main attraction alongside his 30 lions, including several rare ones with black manes; Madam Morelli, ‘Queen of the Jaguars’, with nine in total; Weadon and his trained bears, including Bruin the comical grizzly bear; Mademoiselle Aurora and her ‘Animal Avalanche’ of polar bears; Signor Caruso and his singing hyena; Miller and his Bengal tigers and intelligent elephants; Herr Scholz and Blondie, his pipe-smoking, good-natured elephant; Brandu the Hindoo and his snakes; and others. Some of the performers, like Wahkekeetah, the Moki Indian Princess who danced in front of lions, received separate offers for off-season acts and did not go to Europe.

During a performance on Sunday, July 31st, at 9pm, a lion famously attacked Bonavita in front of 2,000 people. Bostock rushed the stage and managed to pull Bonavita out from under the lion, but not before Bonavita’s right arm was shredded from hand to shoulder, and two of his fingers mangled. Marie Dressler, who was head over heels for Bonavita, would go to Reception Hospital to visit him every day. She often brought a slice of watermelon, Bonavita’s favorite food. Bonavita survived the incident but his arm did not. He went on to continue his performances at Bostock’s in 1905, more popular than ever.

Bostock show spent the summers at Coney Island and the winters in Paris. A variety of animal trainers, each with their own animal act, worked independently under Bostock. Bostock supervised all of the acts during rehearsals to ensure they were entertaining, and was frequently in the audience during actual shows. Bostock’s trainers included Captain Jack Bonavita, who served as the main attraction alongside his 30 lions, including several rare ones with black manes; Madam Morelli, ‘Queen of the Jaguars’, with nine in total; Weadon and his trained bears, including Bruin the comical grizzly bear; Mademoiselle Aurora and her ‘Animal Avalanche’ of polar bears; Signor Caruso and his singing hyena; Miller and his Bengal tigers and intelligent elephants; Herr Scholz and Blondie, his pipe-smoking, good-natured elephant; Brandu the Hindoo and his snakes; and others. Some of the performers, like Wahkekeetah, the Moki Indian Princess who danced in front of lions, received separate offers for off-season acts and did not go to Europe.

During a performance on Sunday, July 31st, at 9pm, a lion famously attacked Bonavita in front of 2,000 people. Bostock rushed the stage and managed to pull Bonavita out from under the lion, but not before Bonavita’s right arm was shredded from hand to shoulder, and two of his fingers mangled. Marie Dressler, who was head over heels for Bonavita, would go to Reception Hospital to visit him every day. She often brought a slice of watermelon, Bonavita’s favorite food. Bonavita survived the incident but his arm did not. He went on to continue his performances at Bostock’s in 1905, more popular than ever.

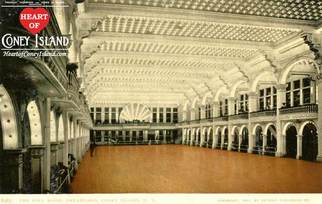

Ballroom, view towards ocean, c. 1905

Ballroom, view towards ocean, c. 1905

Dreamland Ballroom. Dreamland’s ballroom was described as its ‘crowning achievement’ and the first building to be finished during Dreamland’s construction. It sat above the water on the southern end of the Old Iron Pier, which had received a complete makeover as the new Dreamland Pier. The pier now featured two tiers. The top tier housed the ballroom and at the other end, Dreamland’s equally expansive restaurant. The restaurant, 240 feet long and 100 feet wide, was run as a concession by Billie Considine, who also ran the upscale Hotel Metropole’s café and bar at 42nd Street and Broadway in Manhattan. Steamship passengers would use the lower tier to walk between the ships and Dreamland’s pier entrance. This tier was called Dreamland’s Bowery and was lined with minor amusements and arcades. Dreamland advertised its ballroom as the largest in the United States, measuring 100 feet by 250 feet, with 50-foot ceilings, 10,000 lights (another source says 4,300 lights) and capacity to serve 4,000 customers at a time. The floors were polished brilliantly and a band played under a seashell dome at the southernmost end of the ballroom. The entire ballroom was painted a cream white, making the mahogany rails stand out, and the ceilings were paneled in a French Renaissance style. What made Dreamland’s ballroom the grandest at Coney Island was the view of the ocean on three sides and the ocean breeze that would keep dancers cool on warm summer nights. As the Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported shortly before Dreamland opened to the public, “The great tower, gleaming with lights, and the haunting memories of that very, very beautiful ballroom, are going to be things well worth carrying in the mind for months.... Coney Island has certainly come into its own.”

Fighting Flames. This was a larger version of Luna Park’s hit show, Fire and Flames. The massive, 250-foot long façade was located towards the southern end of Dreamland’s east promenade, close to the bathing facilities. Visitors would enter the show, take a seat in a large set of bleachers that faced east, and watch as a hotel suddenly caught fire, trapping many guests inside. The fire alarm would ring and firefighters would arrive, demonstrating the latest in firefighting techniques and technology as they controlled the blaze and rescued people from several stories up. Dozens of actors and trained firefighters would play out a credible storyline.

Dreamland Tower Observatory. Dreamland Tower stood 275 feet tall, had a square base measuring 50 feet by 50 feet, and glowed at night with 100,000 lights. At the top of the tower was an observatory which competed with the panoramic views offered by the still-popular, 300-foot Iron Tower just outside of Dreamland. Kids in particular enjoyed taking the elevator ride to the top.

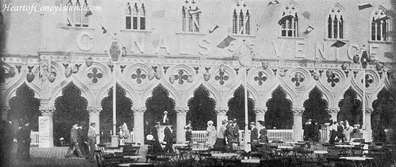

Canals of Venice. A version of the classic Old Mill ride, visitors would step into gondolas and take an indoor ride through a miniature version of Venice. The exterior of the building, facing Dreamland’s east promenade, was a replica of the Doge’s Palace in Venice.

Shoot the Chutes. Dreamland’s double-barreled chutes were designed for the large crowds designers expected. The chutes began out over the ocean and were 316.5 feet long and 96 feet tall, roughly 75 feet of which were above the water during high tide. The key to the chutes was the slope, which determined the speed of the ride.

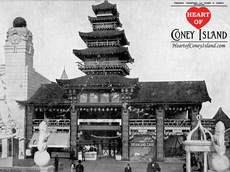

Santos-Dumont Airship No. 9. Alberto Santos-Dumont was a Brazilian scientist and aviation pioneer who designed one of the first controllable dirigibles. He famously won a Paris flying contest between the Parc Saint Cloud and the Eiffel Tower in 1901. The same type of airship he flew was displayed behind a Japanese-themed café at the southeast end of Dreamland. The airship reportedly was to make daily flights over Coney Island, though it is unclear if it ever did.

Fall of Pompeii. This show fit right in among Coney Island’s numerous natural disaster spectacles. It showed the fiery destruction of Pompeii by means of Mount Vesuvius’ volcanic eruption. The illusion had lava, smoke, rocks and even ashes.

Additional Attractions. Dreamland had a 50-person band that would play by Dreamland Tower. It had the largest infant incubator exhibit, borrowing the idea from Luna Park, and also hired away Luna Park’s Wormwood’s Dog and Money Circus. Dreamland had a large scenic railway roller coaster built by L.A. Thompson, a Submarine Boat Moccasin simulation that imitated Luna Park’s 20,000 Leagues under the Sea, a funny room, an aquarium stocked with exotic fish, a Japanese café, free acrobatic acts in the center of the park and numerous other attractions. Broadway stars also were given concessions and appeared at the park daily. These included Marie Dressler, who sold Dreamland’s popcorn and peanuts using a small army of young boys; Andrew Mack, who was at the aquarium; and Charley Ross, who was at Midget City.

Canals of Venice. A version of the classic Old Mill ride, visitors would step into gondolas and take an indoor ride through a miniature version of Venice. The exterior of the building, facing Dreamland’s east promenade, was a replica of the Doge’s Palace in Venice.

Shoot the Chutes. Dreamland’s double-barreled chutes were designed for the large crowds designers expected. The chutes began out over the ocean and were 316.5 feet long and 96 feet tall, roughly 75 feet of which were above the water during high tide. The key to the chutes was the slope, which determined the speed of the ride.

Santos-Dumont Airship No. 9. Alberto Santos-Dumont was a Brazilian scientist and aviation pioneer who designed one of the first controllable dirigibles. He famously won a Paris flying contest between the Parc Saint Cloud and the Eiffel Tower in 1901. The same type of airship he flew was displayed behind a Japanese-themed café at the southeast end of Dreamland. The airship reportedly was to make daily flights over Coney Island, though it is unclear if it ever did.

Fall of Pompeii. This show fit right in among Coney Island’s numerous natural disaster spectacles. It showed the fiery destruction of Pompeii by means of Mount Vesuvius’ volcanic eruption. The illusion had lava, smoke, rocks and even ashes.

Additional Attractions. Dreamland had a 50-person band that would play by Dreamland Tower. It had the largest infant incubator exhibit, borrowing the idea from Luna Park, and also hired away Luna Park’s Wormwood’s Dog and Money Circus. Dreamland had a large scenic railway roller coaster built by L.A. Thompson, a Submarine Boat Moccasin simulation that imitated Luna Park’s 20,000 Leagues under the Sea, a funny room, an aquarium stocked with exotic fish, a Japanese café, free acrobatic acts in the center of the park and numerous other attractions. Broadway stars also were given concessions and appeared at the park daily. These included Marie Dressler, who sold Dreamland’s popcorn and peanuts using a small army of young boys; Andrew Mack, who was at the aquarium; and Charley Ross, who was at Midget City.

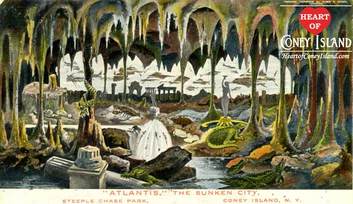

Samuel Friede's Atlantis Under the Sea at Steeplechase

Samuel Friede's Atlantis Under the Sea at Steeplechase

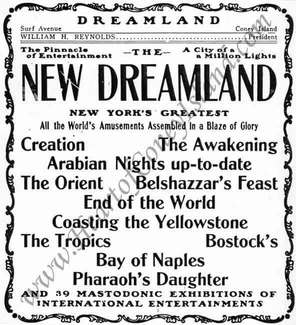

Visiting Dreamland in 1905: Reynolds Doubles Down on his Investment, Licenses 'Creation' and Hosts Chariot Races

The 1904 season had been a fierce battle between Dreamland, Luna Park and Steeplechase. During the winter of 1904, each park undertook extensive renovations and updates ahead of the 1905 season. These costly annual battles would become a consistent theme at Luna Park and Dreamland during the coming seasons. Steeplechase generally was more cost-conscious and pursued a different, more economically-rational business model.

At Steeplechase, Tilyou was finally forced to enter the spending war to upgrade his thoroughly-outdated park. His goal was to invest just enough to keep Steeplechase competitive, without breaking the bank. He added a good number of lights to the park, though nowhere near the number at Luna Park or Dreamland. Tilyou completely renovated Steeplechase’s Bowery entrance, outfitting it with 785 lights and adding Steeplechase’s famous grinning face ‘Tillie’. Steeplechase’s rose garden was improved and a new L.A. Thompson scenic railway was installed. Samuel Friede, the developer of several popular attractions at the recent St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904, was given several concessions. Friede’s Airship Tower ride rotated slowly as four passenger cars, one on each side of the tower, were elevated almost 300 feet into the air and then descended. The tower cost over $100,000 to build and was decorated with 15,000 white and crimson lights. Friede also installed Atlantis Under the Sea, a perfected version of Thompson’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

At Luna Park, Thompson and Dundy added trees and flowers throughout the park, increased the number of lights, and remodeled the main entrance façade by adding large hanging flower pots. They also changed Luna Park's slogan from 'Thompson & Dundy Shows' to 'The Heart of Coney Island'. The 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea ride was replaced with a new L.A. Thompson scenic railway called the Dragon’s Gorge. The Fall of Port Arthur, an attraction recreating the recent Japanese takeover of a heavily-fortified Russian naval fortress in 1904, was also installed. Thompson and Dundy also expanded the circus area greatly and also installed a 75-foot ramp was installed for a new and heavily-advertised Human Torpedo show.

At Dreamland, Reynolds appears to have figured that if he was in for a penny, he was in for a pound. Dreamland spent over $500,000, an absolutely incredible sum at the time, on an extensive array of improvements and additions. Reynolds’ strategy must have been to conclusively outshine both Luna Park and Steeplechase once and for all.

The 1904 season had been a fierce battle between Dreamland, Luna Park and Steeplechase. During the winter of 1904, each park undertook extensive renovations and updates ahead of the 1905 season. These costly annual battles would become a consistent theme at Luna Park and Dreamland during the coming seasons. Steeplechase generally was more cost-conscious and pursued a different, more economically-rational business model.

At Steeplechase, Tilyou was finally forced to enter the spending war to upgrade his thoroughly-outdated park. His goal was to invest just enough to keep Steeplechase competitive, without breaking the bank. He added a good number of lights to the park, though nowhere near the number at Luna Park or Dreamland. Tilyou completely renovated Steeplechase’s Bowery entrance, outfitting it with 785 lights and adding Steeplechase’s famous grinning face ‘Tillie’. Steeplechase’s rose garden was improved and a new L.A. Thompson scenic railway was installed. Samuel Friede, the developer of several popular attractions at the recent St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904, was given several concessions. Friede’s Airship Tower ride rotated slowly as four passenger cars, one on each side of the tower, were elevated almost 300 feet into the air and then descended. The tower cost over $100,000 to build and was decorated with 15,000 white and crimson lights. Friede also installed Atlantis Under the Sea, a perfected version of Thompson’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea.

At Luna Park, Thompson and Dundy added trees and flowers throughout the park, increased the number of lights, and remodeled the main entrance façade by adding large hanging flower pots. They also changed Luna Park's slogan from 'Thompson & Dundy Shows' to 'The Heart of Coney Island'. The 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea ride was replaced with a new L.A. Thompson scenic railway called the Dragon’s Gorge. The Fall of Port Arthur, an attraction recreating the recent Japanese takeover of a heavily-fortified Russian naval fortress in 1904, was also installed. Thompson and Dundy also expanded the circus area greatly and also installed a 75-foot ramp was installed for a new and heavily-advertised Human Torpedo show.

At Dreamland, Reynolds appears to have figured that if he was in for a penny, he was in for a pound. Dreamland spent over $500,000, an absolutely incredible sum at the time, on an extensive array of improvements and additions. Reynolds’ strategy must have been to conclusively outshine both Luna Park and Steeplechase once and for all.

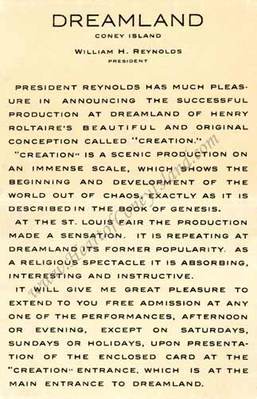

Invitation to Creation (1905)

Invitation to Creation (1905)

Creation. Dreamland’s most extensive renovation for the 1905 season was the installation of Creation at a cost of $250,000. Creation was an illusion-based show conceived of by Henry Roltair. It had been the most popular attraction at the recently-concluded St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904. Creation visually retold the Biblical story in Genesis of how the Earth was formed in six days, culminating in the testing of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. As described by Harper's Weekly in its July 8, 1905, issue:

'There is a religious awe embraced in the contemplation of 'Creation,' a panoramic spectacle illustrating the story of Genesis. No one could possible help being affected by that vivid panorama of old earth in the making, accompanied by the solemn voice of the lecturer, who, with the showman's instinct for the verity that lurks in incongruity, proves his case by adhering almost literally to the Scriptural account. Not even when Adam, in all the nakedness of a suit of underwear which wrinkles as he walks, is discovered by Eve, similarly attired, does the scene lose its spell. At least no one suggests that the spectacle has come perirously near to blasphemy.'

The show ran roughly once an hour, every day of the week. Over half of Dreamland’s Surf Avenue frontage, including Dreamland’s prior main entrance and two amusement buildings, was torn down to make room for the new building. The Johnson carousel also was moved. The new building was a mammoth 150 feet long, 200 feet deep and 90 feet tall. The new main entrance to Dreamland along Surf Avenue was integrated into the building.

Religious groups initially were ecstatic about Creation coming to Coney Island. Surely, it was a sign that Dreamland also espoused their strict moral virtues. Heads began to turn and parents shielded their children’s eyes as construction progressed, however. A 30-foot tall, 100-ton topless statue of a female angel advertising Creation was erected over Dreamland’s new main gates facing Surf Avenue. This seemed unthinkable in a time when proper women had to wear long, formless dresses even when bathing in the ocean. Police quickly responded by making Dreamland put clothes on the statue. Surprisingly, it was a religious group that had the police orders reversed, on the basis that partial nudity was acceptable in the context of providing religious education to the masses. The Bowery patrons certainly must have cheered this outcome as well.

'There is a religious awe embraced in the contemplation of 'Creation,' a panoramic spectacle illustrating the story of Genesis. No one could possible help being affected by that vivid panorama of old earth in the making, accompanied by the solemn voice of the lecturer, who, with the showman's instinct for the verity that lurks in incongruity, proves his case by adhering almost literally to the Scriptural account. Not even when Adam, in all the nakedness of a suit of underwear which wrinkles as he walks, is discovered by Eve, similarly attired, does the scene lose its spell. At least no one suggests that the spectacle has come perirously near to blasphemy.'

The show ran roughly once an hour, every day of the week. Over half of Dreamland’s Surf Avenue frontage, including Dreamland’s prior main entrance and two amusement buildings, was torn down to make room for the new building. The Johnson carousel also was moved. The new building was a mammoth 150 feet long, 200 feet deep and 90 feet tall. The new main entrance to Dreamland along Surf Avenue was integrated into the building.

Religious groups initially were ecstatic about Creation coming to Coney Island. Surely, it was a sign that Dreamland also espoused their strict moral virtues. Heads began to turn and parents shielded their children’s eyes as construction progressed, however. A 30-foot tall, 100-ton topless statue of a female angel advertising Creation was erected over Dreamland’s new main gates facing Surf Avenue. This seemed unthinkable in a time when proper women had to wear long, formless dresses even when bathing in the ocean. Police quickly responded by making Dreamland put clothes on the statue. Surprisingly, it was a religious group that had the police orders reversed, on the basis that partial nudity was acceptable in the context of providing religious education to the masses. The Bowery patrons certainly must have cheered this outcome as well.

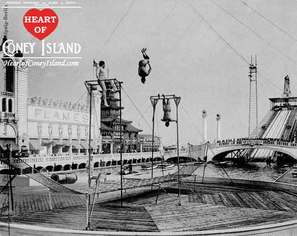

Dreamland also finally finished construction of its Leapfrog Railway, which was supposed to have been ready the prior season. This ride was a unique engineering marvel. The Leapfrog Railway’s elevated tracks ran out over the ocean between the Chutes and New Iron Pier. Two custom-designed trains would move toward each other along a single track. One would slowly climb over the top of the other via a track attached to the roof of the other train that served as a mobile bridge. While the ride never had an accident during the years it operated, it eventually was shut down because of potential liability reasons as no insurer would insure it or the aquatic demise of its passengers, should a train fall off of the tracks.

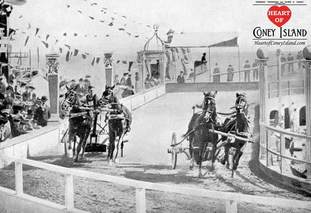

The central court area around Dreamland’s lagoon was rebuilt into the world’s largest Roman-style hippodrome track, a Circus Maximus of sorts, to allow for shows and races in addition to the existing acrobatic acts. Roman legions paraded around, ostriches raced horses, and monkey rode ponies. The free show culminated in a realistic four-chariot race around the track.

A litany of other changes rounded out Dreamland’s update for the 1905 season:

Hell Gate. Hell Gate replaced Submarine Boat. Hell Gate was ride in which a whirlpool realistically appeared to slowly suck a boat below the water’s surface. Passengers would then see the inside of the earth, with the ride finishing with an explosion. As described by Harper's Weekly in its July 8, 1905, issue:

'In an open-fronted building in Dreamland has been constructed a fifty-foot whirlpool. The water swirls terrifyingly towards the centre, and boats crowded with passengers describe a constantly narrowing circle, until before the eyes of the astonished spectators they dive into the middle of the pool. It is a clever device, that of admitting all the world fee to see the boats take the plunge, for every one is eager immediately to take the plunge for himself and see what happens beneath the pool. As a matter of course, it is very pleasant down there. The 'pool' is merely a spiral trough made of wood and iron, through which the water carries the boats to the centre, where the slope suddenly dips and allows them to slip beneath the outer rims of the spiral into a subterranean channel which follows a tortuous course under the building. There are scenes by the way intended to corroborate the popular conception of the earth's interior, and these are about as true to nature as those which we found on the moon [editor: reference to Luna Park's Trip to the Moon ride, which the writer enjoyed in spite of some fantasy-like artistic liberties the ride's creators took when designing the moon's surface], so that by the time the spectators above are beginning to wonder what has happened to the boat, the passengers have had a surfeit of subterranean horrors, and are shot up through one side of the pool to the surface.'

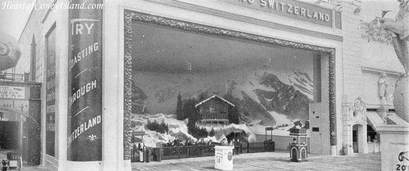

Additional Improvements for 1905. 'Touring through Europe in an Automobile' replaced Fall of Pompeii; cars were popular novelties at the time, and passengers would ride a guided car along a track while passing various European landscapes. Fighting Flames was entirely redone for novelty value at a cost of $40,000; the latest lifesaving devices of the New York Fire Department would be exhibited. Sir Hiram Maxim’s Airship was erected near Dreamland Tower. A sensation at Earl’s Court in London, it was a 150-foot tall tower than revolved twelve attached ‘airplane boats’ rapidly around in circles, at a total diameter of 186 feet when at full speed, traveling at 40 miles per hour. Renovations were made to Coasting through Switzerland, Canals of Venice and L.A. Thompson’s Scenic Railway. An attraction called the Flea Circus was added to Midget City. Many of these changes, including Creation and Midget City’s Flea Circus, were not completed until several weeks after Dreamland opened on May 13th, 1905. Alongside similar delays at Luna, including the Igorrotes not appearing on opening day, many visitors who had gone to see all of the advertised new attractions left Coney Island rather upset.

Hell Gate. Hell Gate replaced Submarine Boat. Hell Gate was ride in which a whirlpool realistically appeared to slowly suck a boat below the water’s surface. Passengers would then see the inside of the earth, with the ride finishing with an explosion. As described by Harper's Weekly in its July 8, 1905, issue:

'In an open-fronted building in Dreamland has been constructed a fifty-foot whirlpool. The water swirls terrifyingly towards the centre, and boats crowded with passengers describe a constantly narrowing circle, until before the eyes of the astonished spectators they dive into the middle of the pool. It is a clever device, that of admitting all the world fee to see the boats take the plunge, for every one is eager immediately to take the plunge for himself and see what happens beneath the pool. As a matter of course, it is very pleasant down there. The 'pool' is merely a spiral trough made of wood and iron, through which the water carries the boats to the centre, where the slope suddenly dips and allows them to slip beneath the outer rims of the spiral into a subterranean channel which follows a tortuous course under the building. There are scenes by the way intended to corroborate the popular conception of the earth's interior, and these are about as true to nature as those which we found on the moon [editor: reference to Luna Park's Trip to the Moon ride, which the writer enjoyed in spite of some fantasy-like artistic liberties the ride's creators took when designing the moon's surface], so that by the time the spectators above are beginning to wonder what has happened to the boat, the passengers have had a surfeit of subterranean horrors, and are shot up through one side of the pool to the surface.'