Coney Island History: The Story of Captain Paul Boyton and Sea Lion Park

|

This is the first of four articles on Coney Island's iconic amusement parks. Subsequent articles on Steeplechase Park, Luna Park, and Dreamland build on this article.

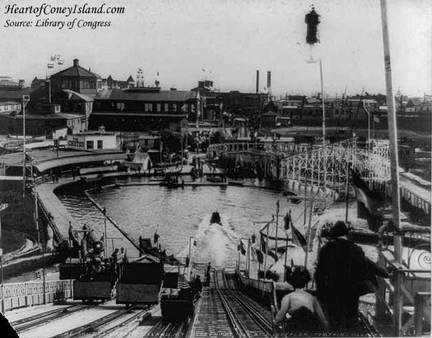

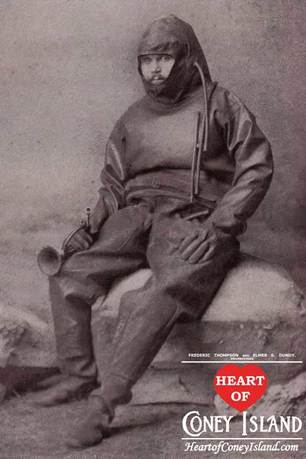

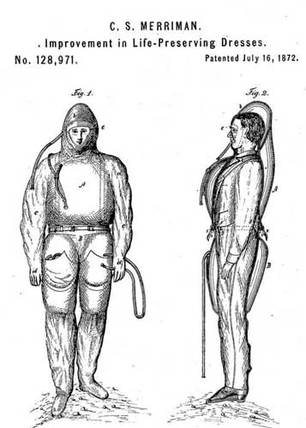

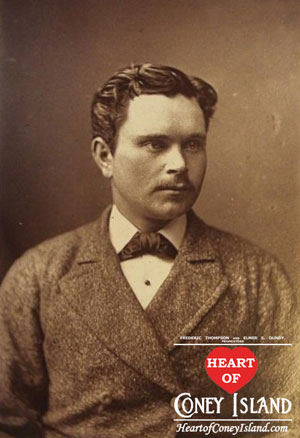

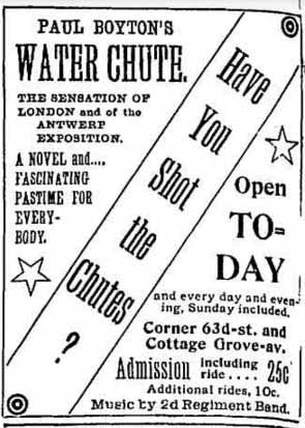

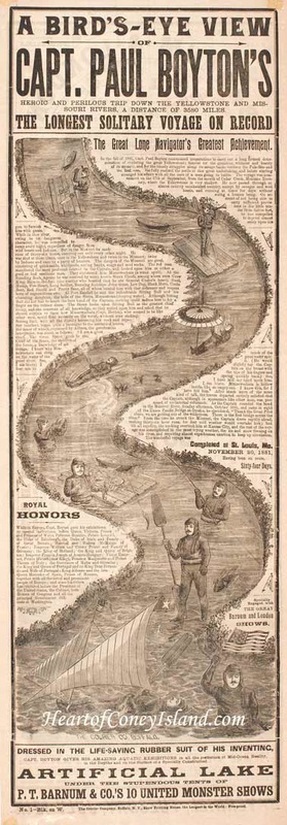

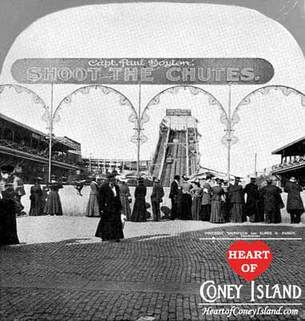

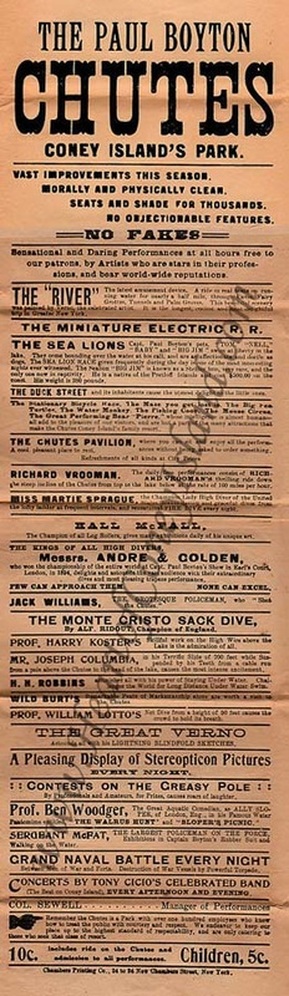

Sea Lion Park is the predecessor to all modern enclosed amusement parks, including the three great amusement parks that subsequently rose to fame at Coney Island. The creator of Sea Lion Park, Captain Paul Boyton, was a world-famous aquatic daredevil and showman who traveled the world's rivers in an inflatable rubber suit. Boyton was greeted by crowds of tens of thousands wherever he traveled in the United States and was received royal receptions when touring European countries. Boyton pioneered the idea of asking customers to pay an admission fee to enter a large enclosed area containing multiple amusement rides and activities. The idea was Boyton's adaptation of how circuses charged customers to enter an enclosed tent, which Boyton observed while touring with P.T. Barnum's circus for the 1887 season. While all major amusement parks today follow this model, prior to Boyton, amusement rides generally were individually-owned and operated, and customers paid on a per-ride basis. Boyton tested his idea briefly by opening Paul Boyton's Water Chutes Park in Chicago in 1894, just after the Chicago World's Fair. Seeing potential, he came to Coney Island the following season and opened the more complete Sea Lion Park in 1895. George Tilyou subsequently copied Boyton's idea when he created Steeplechase Park at Coney Island in 1897, as did Luna Park and Dreamland less than a decade later. The stories of Sea Lion Park and Paul Boyton are exceptionally entertaining but largely forgotten. There is little surviving visual record of Sea Lion Park because it predated both when mobile cameras were readily available and the American postcard craze of the early 1900s. The latter, by contrast, provides a major visual historical record for Steeplechase, Luna and Dreamland parks. Sea Lion Park suffers from being 'out of sight, out of mind'. Boyton's Beginnings and Rubber Suit (1848-1874) Born in 1848, Paul Boyton grew up playing by the shores of the Allegheny River outside of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Though born in Ireland, Boyton was a fanatical American patriot and evaded the question of birthplace by stating that his first memories were of the United States. Boyton would display an American flag prominently at any opportunity during his global travels throughout his life, and many advertisements featuring his later shows would feature an American flag at his insistence. While serving as a lifeguard in Atlantic City during the summers of 1873 and 1874, Boyton made seventy-one life-saving rescues. Many people could not swim well at the time, yet steamships were a preferred means of long-distance travel. Boyton concluded that many people's lives could be saved in an emergency if passenger steamships stocked full-body inflatable, water-proof rubber suits like the one invented by Merriman in 1872, which Boyton had become obsessed with over the two summers. Boyton claims that the desire to save lives led him to do what he did next. It seems likely that he was equally driven by his life-long desire for adventure and the possibility of developing a business out of selling the suits, as Boyton was the consummate entrepreneur. Rise to Fame (1874) Boyton hatched a scheme to publicize Merriman's rubber suit in October of 1874. His plan was to board a ship from New York City to Europe and jump overboard once they were two-hundred miles off of the American coast. Carrying only an axe, some flares and an inflatable waterproof bag that could support fifty pounds of fresh water and other provisions, Boyton would then swim his way back to shore. The only problem is that none of the ship captains Boyton innocently confided in wanted any part in what sounded like a suicide plan. His obsession to see the plan to fruition only grew stronger as newspaper articles surfaced ridiculing Boyton's idea. After failed attempts to board various ships, Boyton finally sneaked onto a passenger ship heading to Ireland by pretending to be a worker loading cargo onto the ship. The crew stopped Boyton from jumping overboard off of American waters, but Boyton somehow managed to convince them to let him go ahead with his plan when they reached the coast of Ireland, assuming the weather was reasonable. The captain kept his promise and Boyton almost died when a massive storm materialized shortly after he left the ship. When Boyton reached the shore hours later, he was both utterly exhausted and in a state of shock at having actually survived. Boyton staggered his way into a small town still wearing his full rubber gear, quite a sight to behold for all who saw him. Crowds gathered as initial rumors spread that the strangely-dressed American had survived a shipwreck, because no one believed someone would willingly jump off of a ship. Boyton tried to dispel, with only modest success, subsequent rumors that he had managed to swim all the way from New York City. Hailed as a local celebrity, the townspeople sent Boyton to the city of Cork by train to await the arrival of his ship. There, people at first refused to believe Boyton, until his actual ship arrived and passengers confirmed the story and invited him out for a night of celebration. The next morning, a promoter came to Boyton's hotel room and offered him a contract worth roughly US$125 to tell his story in front of a large auditorium in Cork. Boyton, penniless, and at first thinking the man was joking until he offered to pay a portion upfront, instantly agreed and rapidly acquired a taste for the spotlight. Crosses the English Channel and Tours Europe (1875-1879) Shortly thereafter, in May of 1875 and at the age of twenty-seven, on his second attempt, Boyton became first person to cross the English Channel unaided except for his suit and a paddle. A ship and reporters followed him from the French side to the English shore, where large crowds greeted him and congratulatory telegrams arrived from the Queen of England and other royals. Boyton became a worldwide celebrity overnight. Over the next five years, he toured Europe and many of its most precarious rivers, paying for his tour by giving exhibitions wherever he went, often for charity. He claims to have made approximately US$1,750 per week during this time, in spite of his agent's large take. Going down waterfalls and through rapids was a point of honor to Boyton, who even ate from provisions he kept in a small tow-behind container and napped while floating downstream so as to not have to get out of the water. He was inseparable from his bugle, which he would play to announce his presence to people gathered on the shore and who cheered as he passed by. Major American newspapers provided ongoing front-page updates of his progress throughout Europe. Boyton Earns the Title of Captain (1880) Boyton returned to New York City, now famous and having acquired some savings in spite of his loose-spending ways, in early 1879. He was promptly invited to give an exhibition to Congress and spent much of the rest of the year on tour at various resorts and beaches, and having a 'well-earned good time'. In October of 1880, a Peruvian government agent approached Boyton regarding a secret mission as Boyton was walking down Broadway in New York City. Peru was at war with Chile at the time, and hired Boyton to blow up Chilean warships embargoing Peru. Boyton agreed to travel to South America on two conditions. First, the Peruvians had to pay him a $100,000 success-based commission for the first Chilean warship he sank, $125,000 for the second, and $150,000 for the third. These were incredible sums at a time when the president of the United States made $50,000 annually, a ship captain made $1,500 annually and a common soldier or factory worked cleared only about $125 annually. Second, Boyton asked to be named a captain in the Peruvian navy. Thereafter, Boyton relished being called 'Captain' or 'Cap'. Boyton nearly succeeded in attaching a torpedo to a Chilean warship, but news spread quickly of his assignment. The Chileans, petrified, adopted a strict policy of shooting first and asking questions later. Several seals were the unfortunate victims of this policy, the Chileans taking no chances with any clever Boyton disguises. Boyton, annoyed at seeing his bounty slipping away, began floating empty barrels towards the Chilean warships, laughing with his comrades about the thousands of dollars the Chileans were wasting in ammunition to sink the barrels. He was once captured by the Chileans on land, but unbelievably managed to escape by convincing them his name was Pablo Delaport and that he was a telegraph repairman on his way to a job. Settles Back in the United States (1881-1894) Taking no further chances, after this narrow escape, Boyton immediately returned to the New York City. Predictably, he arrived 'without a cent in his pocket' because of his spendthrift lifestyle. In May of 1881, he traveled down the Mississippi River, and in September, the full length of the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers. On both journeys, he gave shows at many towns along the way. Over the next ten years, Boyton did all kinds of things, including opening a bar in New York City and later traveling as the main attraction of P.T. Barnum's circus for the 1887 season. Boyton's Water Chute (1894) Boyton moved to Chicago in 1888. In 1893, he visited the popular Chicago World's Fair, better known as the Columbian Exposition. He noted the popularity of the fair's Midway, which contained numerous new amusement attractions such as the first Ferris wheel. Always up for a new project and tinkering with things in his spare time, he quickly devised a business idea to create an aquatic ride of his own. Boyton's plans were already in motion by the time the Columbian Exposition closed in October of 1893. While in Europe, Boyton had seen the idea for an amusement ride called 'Shooting the Chutes'. In it, passengers boarded a large rowboat which, when released, sped rapidly down a large incline and into a lake, spraying passengers with water. Boyton returned to Europe, acquired the rights and set about perfecting the ride. By May of 1894, Boyton was running water chutes at both the Earlscourt World's Water Show in London and the Antwerp World's Fair of 1894. In London it made quite a splash, with newspapers reporting that the 'serious and solemn-faced Home Secretary' of the U.K., H.H. Asquith, had skipped out on his scheduled meeting with the National Women's Temperance Association to ride Boyton's water chute with his wife. This faux pas did not stop Asquith from later becoming prime minister. Back in the United States, Paul Boyton's Water Chute opened close to the Chicago World's Fair grounds on July 4th of 1894. Boyton himself apparently was such a busy man that he missed opening day, a fact not lost on the Chicago Tribune: "Chuting is the latest outdoor sport, and it was inaugurated yesterday successfully at Sixty-third street and Cottage Grove avenue. A boat sufficiently large to comfortably seat eight persons glides down an incline at a rate of forty miles an hour and gracefully floats across an artificial lake 300 feet long. [Note: Elevator cars holding sixteen people would bring passengers up the ramp.] At the sides of the boat is arranged a series of protecting boards, which sprays the water, thus producing all the effects of the oar when in motion. The length of the incline is 300 feet, making the ride a total of 600 feet. Three thousand persons visited the grounds during the day. Paul Boyton, who is the chief spirit in the new enterprise, is abroad, but will shortly return. The chutes will be in operation from 11am to 10:30pm daily." Sea Lion Park (1895-1902) Based on the success of his shoot-the-chutes in Chicago and London, Boyton saw the opportunity to mount a larger and more comprehensive amusement venue in New York City. He opened Sea Lion Park at Coney Island on Thursday, July 4th, 1895. It occupied the twenty-two acre site (one source says sixteen acre) where Pain's The Carnival of Venice fireworks show previously stood, just behind the by-then-infamous Elephant Hotel. The park and its main attraction, Boyton's now-perfected Shoot the Chutes ride, were enclosed by a high wooden fence with a single entry gate. Sea Lion Park is the first amusement park of significance to use the modern business model of charging an admission fee to enter an enclosed park offering multiple rides and activities, similar to the way Disney and Six Flags operate today. Numerous additional amusement and social attractions distinguished Sea Lion Park from Boyton's smaller prior endeavors in Chicago, London and Antwerp. Boyton purchased and installed Lina Beecher's notorious Flip-Flap Railway, the first looping roller coaster in America. This ride made passengers black out from the extreme g-forces that its tight and perfectly-circular loop created. Boyton also put on large water shows in the artificial lake with group of five (and possibly as many as forty) trained sea lions and other performers who did tricks using Boyton's numerous and unusual aquatic inventions, including inflatable shoes that allowed the performers to walk on water. A band provided full-time music throughout the day. The park had over one-hundred employees in total, and including several world-caliber divers, swimmers and stuntment. For opening day, Boyton left nothing to chance. Invitations were sent in advance to celebrities and diplomats, and advertisements were placed in newspapers. Ironically for a water park, and in a sign of what eventually was to come, torrential rains on July 4th left West Brighton a flooded mess. Only 10,000 of the 100,000 or more typical holiday visitors made their way to Coney Island. Travel was almost impossible as dirt streets became muddy swamps and 'attractions vanished under the downpour and left only and air of desolation.... Never before has Coney Island had such a Fourth of July.' The lack of attendance did not prevent the same New York Times reporter from asserting in the day's account that 'hereafter it will be the proper thing at Coney Island to 'shoot the chute' of the Paul Boynton [sic] Company.' Boyton scrambled to re-issue invitations for Friday, July 5th, when bad weather again hampered a large turnout. Only by Sunday did a crowd of any size begin to show. Two weeks later, on Sunday, July 21st, a heat wave packed Coney Island with a hoard of 120,000 estimated visitors. Restaurants were at capacity and beer taps ran dry as many day-trippers were forced to wait until 7pm to return home, when electrical power finally was restored to the Prospect Park trolley service. Over 30,000 people supposedly visited the bath houses to go for a swim at the beach, and rental swimsuits were being reissuing as quickly as they were returned, still wet, to waiting customers. Boyton did not dispute reports that 27,000 people rode his chutes that day. Someone doing careful calculations may have pointed out that all of these figures must have been greatly exaggerated, as this would have required launching a full boat of eight passengers every 13 seconds without stop from Noon to Midnight. During its first two seasons, rarely a week passed at Sea Lion Park without something unusual and potentially newsworthy happening. The ever-affable Boyton made newspapers for quickly donning his rubber suit to recover the wedding ring of a 'Mrs. Larke of Bay Ridge' after she inexplicably managed to drop it into the lagoon while riding the chutes. A week later, the well-known laundry magnate Sing Lee fell overboard into the lagoon, needing a good washing himself as a result, and initially causing panic among the crowd until it became clear that the lagoon was only two-and-one-half-feet deep. Boyton held contests to see which animals could ride the chutes best: dancing bears liked it, lions tolerated it and baby elephants would go nowhere near it. Taking advantage of the bicycle-riding craze in Europe and the United States (the modern safety bicycle had just been invented a few years earlier), he even invented the sport of riding down the Chutes on a bicycle and hosted 1890s-style 'X-Games' competitions in both Sea Lion Park and London. And, to top it all off, Boyton's adopted pet baby alligator, which supposedly had arrived mysteriously one day in a box postmarked from Florida, was lost in a fight with a local Newfoundland dog known as Nero. It is a safe bet that these and many other events that took place at Sea Lion Park were driven by Boyton's love of publicity. Random inebriated patrons who stumbled over from the Bowery, like Sing Lee, also kept life at Sea Lion Park exciting. In spite of Boyton's fame, marketing ability and the money he reinvested into Sea Lion Park, by 1901, it appears that Steeplechase Park and other independent rides were taking their toll. Sea Lion Park had always been on the less desirable side of Surf Avenue, across from instead of adjacent to all of the activity at the bath houses and Bowery. Sea Lion Park was a specific destination rather than a place with natural foot traffic. It became harder to draw crowds as the novelty wore off, which is why Steeplechase's Tilyou later underestimated the success Luna Park could have on the same spot. In the winter of 1901, Boyton stated that he was investing $100,000 in improvements ahead of the 1902 into 'Sea Lion Park, the new and extensive amusement enterprise, the largest in Greater New York'. Boyton, as general manager, advertised for concessionaires for the 1902 season: "Fine sites for small Wild West, Circus, Ostrich Farm, Indian, Philippine or Japanese Village, Animal Shows, etc., etc. In this Park, only the best and cleanest. If you have anything good and new write for particulars, or come and see the Park." Boyton's investment, albeit likely exaggerated, could not have come at a worse time. The 1902 season proved to be financially disastrous for all Coney Island businesses because it rained almost every weekend. Recently married and with two children, Boyton decided to pursue other aspects of his life. It is ironic that rain caused the great aquatic showman to throw in the towel. Always a gambler and never afraid of the weather, Boyton had even proposed reinvesting all of his profits to keep his park open during the winter of 1895 if the railroads would keep service running, though it seems unlikely that they obliged. Thompson and Dundy, fresh from their scuffle with Steeplechase Park's Tilyou, bought out Boyton's remaining long-term lease starting October 1, 1902. With the lease came everything that Boyton had at Sea Lion Park, including his sea lions and Topsy, the infamous elephant that Boyton had purchased from Forepaugh's Circus early in the spring of 1902. Thompson and Dundy incorporated Boyton's Chutes and lagoon into their Luna Park for the 1903 season. Sea Lion Park's Shoot the Chutes survived at Luna Park for the next forty years, until the entire park burned in 1944. The success of Boyton's enclosed-park business model had in the meantime led another entrepreneur, George Tilyou, to copy it and open Steeplechase Park in 1897. Its history is covered in the next article. Next: Tilyou's Steeplechase Park Return to Coney Island History Homepage |

Video: Sea Lion Park (1896)

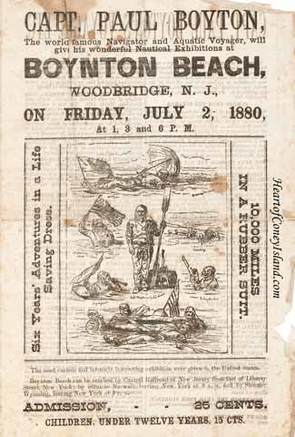

Program for one of Boyton's solo exhibitions in 1880, this one at Boynton Beach. This program is special because of the beach's name. It drove Boyton absolutely crazy when reporters frequently misspelled his name as Boynton. The inside of this program even devotes a paragraph calling attention to the seriousness of the issue.

Sea Lion Park 'Diving Horses' Video (1899)

(Higher resolution available at Library of Congress) |

Addendum: Captain Paul Boyton's Tour with Barnum's Circus (1887)

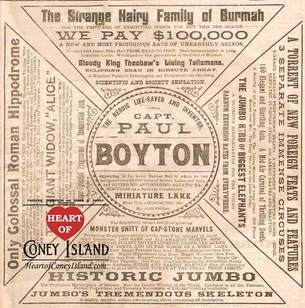

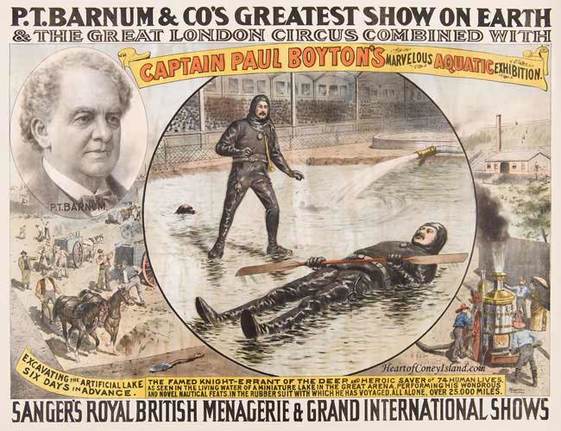

Poster advertising Boyton's appearance in Newburyport, MA, on July 18, 1887.

Poster advertising Boyton's appearance in Newburyport, MA, on July 18, 1887.

Batman and Barnum may not have much in common, but seeing Barnum's portrait in this rare poster surely would make Heath Ledger ask, "Why - so - serious?" It turns out that there's a really good answer.

Circuses had a really difficult line to toe in the mid-to-late 1800s. They needed to be fun and entertaining to attract customers. Fun, however, was a four-letter word to the religious establishment at the time. Want to play a board game with the family on Christmas, or have Sunday funday on your one free day a week? Think again. Many viewed that as immoral. Religion was a controlling force in daily life outside of the larger cities. Even as late as 1920, the Women's Christian Temperance Movement had enough sway to get the Constitution changed to ban alcohol.

The last thing Barnum therefore could afford to do was smile on his posters. That would have resulted in boycotts for Sunday and holiday performances to say the least, if not general boycotts by smaller towns altogether. The circus had to advertise itself as "moral" and "didactic," to quote words Barnum frequently used in advertisements. Joining forces with Sanger's Menagerie, a traveling zoo, was no coincidence. This allowed Barnum to claim that going to the circus was an educational experience for children. Boyton's flyers for these performances gave the act an almost scientific aura, focusing on Boyton's demonstration of his novel rubber suit that let him walk on water, at least if one believed the poster. Never mind that by 1887, everyone just wanted to see a slightly washed-up Boyton in person, given he still was one of the most famous people in the world. After all, people living outside of larger urban areas had no television and no easy means of travel, so traveling shows and circuses were one of the few ways to break the monotony of daily life by seeing famous people or unusual things.

This poster, one of only two known to survive, was designed and printed by the famous Strobridge Lithographing Company. It would have been hung in Newburyport by Barnum's advance marketing team roughly two or three weeks ahead of the circus arriving in town. They would have papered just about every wall in the town with various designs. This 30" x 40" poster was the standard size. Larger multi-sheet posters would have been placed on larger walls. The circus stayed in each town only one day (Monday, July 18th, in this case) or two days, before moving onto the next town. Given the expense of creating a "miniature lake" for the heroic "knight-errant of the deep" at each stop, Barnum relied on Boyton's fame to attract just about everyone in the town to make the economics work.

Boyton agreed to tour with Barnum for just one year, 1887, after completing nearly a decade of tours and adventures on his own. Seven years later, Boyton opened the first enclosed amusement park in the world, showcasing his Shoot-the-Chutes ride in Chicago the year after the Chicago World's Fair. The following year, he brought the same idea to Coney Island and opened Sea Lion Park, where he continued to perform for audiences.

Circuses had a really difficult line to toe in the mid-to-late 1800s. They needed to be fun and entertaining to attract customers. Fun, however, was a four-letter word to the religious establishment at the time. Want to play a board game with the family on Christmas, or have Sunday funday on your one free day a week? Think again. Many viewed that as immoral. Religion was a controlling force in daily life outside of the larger cities. Even as late as 1920, the Women's Christian Temperance Movement had enough sway to get the Constitution changed to ban alcohol.

The last thing Barnum therefore could afford to do was smile on his posters. That would have resulted in boycotts for Sunday and holiday performances to say the least, if not general boycotts by smaller towns altogether. The circus had to advertise itself as "moral" and "didactic," to quote words Barnum frequently used in advertisements. Joining forces with Sanger's Menagerie, a traveling zoo, was no coincidence. This allowed Barnum to claim that going to the circus was an educational experience for children. Boyton's flyers for these performances gave the act an almost scientific aura, focusing on Boyton's demonstration of his novel rubber suit that let him walk on water, at least if one believed the poster. Never mind that by 1887, everyone just wanted to see a slightly washed-up Boyton in person, given he still was one of the most famous people in the world. After all, people living outside of larger urban areas had no television and no easy means of travel, so traveling shows and circuses were one of the few ways to break the monotony of daily life by seeing famous people or unusual things.

This poster, one of only two known to survive, was designed and printed by the famous Strobridge Lithographing Company. It would have been hung in Newburyport by Barnum's advance marketing team roughly two or three weeks ahead of the circus arriving in town. They would have papered just about every wall in the town with various designs. This 30" x 40" poster was the standard size. Larger multi-sheet posters would have been placed on larger walls. The circus stayed in each town only one day (Monday, July 18th, in this case) or two days, before moving onto the next town. Given the expense of creating a "miniature lake" for the heroic "knight-errant of the deep" at each stop, Barnum relied on Boyton's fame to attract just about everyone in the town to make the economics work.

Boyton agreed to tour with Barnum for just one year, 1887, after completing nearly a decade of tours and adventures on his own. Seven years later, Boyton opened the first enclosed amusement park in the world, showcasing his Shoot-the-Chutes ride in Chicago the year after the Chicago World's Fair. The following year, he brought the same idea to Coney Island and opened Sea Lion Park, where he continued to perform for audiences.