Coney Island History: The Rise and Fall of John 'Boss' McKane (1868-1894)

John Y. McKane, c. 1884

John Y. McKane, c. 1884

When the Gunther Railroad first chugged into Coney Island in 1862, John Y. McKane was a 21-year-old chap of Scottish-Irish descent living in Gravesend and learning the carpentry trade. By 1866, he had branched off on his own as a carpenter and builder in the Sheepshead Bay area. Two years later, in 1868, he got his first taste of public office, as a constable with a one-year term. Diligent and hardworking, McKane continued to operate his construction business on the side. He was the kind of man who dreamed the American dream, who sought to make something of himself. He got married, settled down at Sheepshead Bay and had a family.

McKane quickly realized that it would be both more profitable and less backbreaking if he became a building contractor rather than a tradesman. If he could source construction contracts, he could hire others to lift all of the heavy beams and bang on nails for him.

In the course of obtaining building permits, McKane got to know the inner workings of the Gravesend town government. Decades earlier, in 1834, the State of New York had combined a number of towns (officially known as ‘villages’) at the west end of Long Island to form the City of Brooklyn. Five of these towns, including Gravesend, were allowed to retain their prior self-governing status. Their local governments had a great deal of autonomy as to what went on at the local level, including construction and the selective application of law enforcement.

Most of the farmers and businessmen of Gravesend and Coney Island viewed the day-to-day functioning of the local government as a bother and a bore. They were too preoccupied with their livelihoods to concern themselves with such tiresome intricacies. As long as those in charge saw to it that the peace was kept, that the garbage was collected, that the roads were repaired, that the taxes were within reason, and that the brothels were kept out of the public view, they were satisfied to let the job be done by others, particularly as the supervisory salaries were inconsequential.

McKane was not unmindful of such indifference towards political office and seized the opportunity. He realized that political influence would greatly benefit his construction business. It allow him to attain permits that others could not, rezone areas, hold up projects with red tape unless they used his company, and be in the thick of every major construction decision.

McKane set out to become a Commissioner of Common Lands for Gravesend, and was elected to the position in the mid-1870s. This commission was responsible for renting out the large tracts of land that the roughly 200 to 300 heirs of the original thirty-nine Gravesend patentees held under joint ownership for simplicity. These lands included the western half of Coney Island, including most of West Brighton (the original Coney Hook area) and the original Conyne Eylandt to its west, certain rights to the latter still being disputed in courts.

These common lands were leased to the highest bidders, usually for seven year periods, with options for the lessees to renew. Successful bidders for the choicest parcels of Coney Island all happened, by pure coincidence, to be cronies and friends of McKane. Typical winning bids might be $25 a year for Parcel A, and $35 a year for Parcel B. The lessee of Parcel A would then sublease it for $1,500 a year, and the other lessee would sublease his parcel for $3,000 a year. These were staggering profits, considering the value of a dollar in those times.

Some stuffy moralists wanted to know what McKane got out of his deals as Commissioner of the Common Lands. A statistic from several years later might be revealing. By 1884, McKane’s construction company was credited with building nearly two-thirds of all buildings in Coney Island and Gravesend. Among these, he built nearly every hotel except for the three great hotels, the Brighton Beach, Manhattan Beach and Oriental. Apparently, the people who received great deals on the land McKane was renting to them understood that they had to kick back some of the money by hiring his construction company to erect their businesses. Given the frequent need to rebuild because of constant fires at Coney Island, there never was a shortage of work for McKane’s company.

McKane was successfully working other government angles while doling out deals as Commissioner of the Common Lands. By the late 1870s, McKane had worked his way up to Town Supervisor. The latter was the highest position attainable in Gravesend, the equivalent of a city's mayor. As Town Supervisor, he had to keep a watchful eye on the Tax Department and Department of Licenses. Not to worry, for McKane was in charge of those departments as well. McKane magnanimously also served as Gravesend's Commissioner of Water and Gas and Commissioner of the Board of Health.

While engaged in these thankless government tasks, Citizen McKane was a good family man, went to Methodist Church regularly – he was superintendent of its Sunday School – smoked a cigar once in a while but never drank, or at least nothing stronger than sarsaparilla, though on rare occasions he is known to have gone to hell with himself and indulged in a root beer.

Early in 1884, the courts decided that the town government of Gravesend was empowered to distribute the remaining common lands in the most equable manner favored by the electorate. Some wanted the lands to be sold at public auction. McKane instead suggested having the lands appraised and sold to those holding the leases on them, if they wished to buy them. Of course, this benefitted McKane and his cronies. Lessors were likely to get a good deal on the purchase as the appraisers likely were in McKane’s pocket. In turn, they would continue kicking money back to McKane by giving his construction company the ongoing rebuilding work from fires and storms at Coney Island. So, everyone would win except for a diversified group of land owners, many of whom were absentees. In May, 1884, McKane's proposal was approved in a referendum by the voters of Gravesend and Coney Island, thereby putting an end to the leasing of common lands in favor of outright sale.

Later in 1884, the presidential election was held between Grover Cleveland as the Democratic candidate, and James G. Blaine as the Republican one. In Gravesend and Coney Island, the head of the Democratic Party was John Y. McKane, and the head of the Republican Party was John Y. McKane. McKane talked the situation over with his lieutenants, Kenny Sutherland and Dick Newton. After a meeting with the powers at Tammany Hall, McKane decided to side with them and support Cleveland. Word went out to every hotel, restaurant, bar, tonsorial parlor, clip joint and brothel that McKane expected every man to do his duty and vote a straight Democratic ticket. All voting had to be done in Gravesend's city hall, with different rooms in the building provided for the different election districts. Watchers from both parties were assigned to keep an eye out for voting irregularities, or, as we shall see, perhaps to ensure them.

The national election turned out to be exceptionally close, with the outcome hinging on New York State's electoral vote. Cleveland and Blaine were running neck and neck in New York State. The politicians in Democratic and Republican state and national headquarters were biting their nails as they watched the returns seesaw through the following day. Just when it appeared that there might be a tie vote in New York State, in came the returns from Gravesend. A jubilant roar almost lifted the roof of Tammany Hall. McKane had delivered the vote, several thousand for Cleveland, and barely enough for Blaine to compose a football team. Cleveland won New York by a little more than one-thousand votes. When McKane walked down Surf Avenue after the election, people gaped in awe at the man who had put Cleveland in the White House. McKane and a large delegation of his stalwarts were invited to Cleveland's inauguration. They paraded down Pennsylvania Avenue, and then attended the Inaugural Ball. When they got back to Coney Island, they were greeted like conquering heroes by a large crowd.

In March of 1885, the Republicans struck back at McKane by arresting his brother-in-law, Paul Bauer, for allowing gambling in his West Brighton Hotel. Bauer, who was just a bystander in McKane's political feud, served three months in prison. In 1887, Bauer was committed to a mental institution, where he died two years later. William Engeman's half-brother, George Engeman, was also hauled into court on a bookmaking charge, but the district attorney couldn’t make it stick.

McKane took over the management of Bauer's West Brighton Hotel and Casino while Bauer was in the asylum, and succeeded in paying off Bauer's numerous debts. But McKane found it too enervating to continue managing the properties, so shortly thereafter, in 1888, he leased them for three years to Moritz and Aaron Hertzberg, at $30,000 a year.

McKane at this time may have been too occupied with affairs of state to bother with running a hotel, for it was presidential election time again. The Democratic incumbent, Grover Cleveland, was seeking reelection, and his Republican opponent was Benjamin Harrison. McKane was having some differences with the leaders of the Democratic Party of Brooklyn, and decided to throw his support to the Republicans. Possibly, another reason for backing the Republicans was to placate Brooklyn's blue-bloods, who always seemed to be after his hide. Although Cleveland received a greater popular vote, nationally, Harrison took the electoral vote, and became president. Unlike the previous presidential election, the New York State vote did not decide the outcome of this election.

McKane quickly realized that it would be both more profitable and less backbreaking if he became a building contractor rather than a tradesman. If he could source construction contracts, he could hire others to lift all of the heavy beams and bang on nails for him.

In the course of obtaining building permits, McKane got to know the inner workings of the Gravesend town government. Decades earlier, in 1834, the State of New York had combined a number of towns (officially known as ‘villages’) at the west end of Long Island to form the City of Brooklyn. Five of these towns, including Gravesend, were allowed to retain their prior self-governing status. Their local governments had a great deal of autonomy as to what went on at the local level, including construction and the selective application of law enforcement.

Most of the farmers and businessmen of Gravesend and Coney Island viewed the day-to-day functioning of the local government as a bother and a bore. They were too preoccupied with their livelihoods to concern themselves with such tiresome intricacies. As long as those in charge saw to it that the peace was kept, that the garbage was collected, that the roads were repaired, that the taxes were within reason, and that the brothels were kept out of the public view, they were satisfied to let the job be done by others, particularly as the supervisory salaries were inconsequential.

McKane was not unmindful of such indifference towards political office and seized the opportunity. He realized that political influence would greatly benefit his construction business. It allow him to attain permits that others could not, rezone areas, hold up projects with red tape unless they used his company, and be in the thick of every major construction decision.

McKane set out to become a Commissioner of Common Lands for Gravesend, and was elected to the position in the mid-1870s. This commission was responsible for renting out the large tracts of land that the roughly 200 to 300 heirs of the original thirty-nine Gravesend patentees held under joint ownership for simplicity. These lands included the western half of Coney Island, including most of West Brighton (the original Coney Hook area) and the original Conyne Eylandt to its west, certain rights to the latter still being disputed in courts.

These common lands were leased to the highest bidders, usually for seven year periods, with options for the lessees to renew. Successful bidders for the choicest parcels of Coney Island all happened, by pure coincidence, to be cronies and friends of McKane. Typical winning bids might be $25 a year for Parcel A, and $35 a year for Parcel B. The lessee of Parcel A would then sublease it for $1,500 a year, and the other lessee would sublease his parcel for $3,000 a year. These were staggering profits, considering the value of a dollar in those times.

Some stuffy moralists wanted to know what McKane got out of his deals as Commissioner of the Common Lands. A statistic from several years later might be revealing. By 1884, McKane’s construction company was credited with building nearly two-thirds of all buildings in Coney Island and Gravesend. Among these, he built nearly every hotel except for the three great hotels, the Brighton Beach, Manhattan Beach and Oriental. Apparently, the people who received great deals on the land McKane was renting to them understood that they had to kick back some of the money by hiring his construction company to erect their businesses. Given the frequent need to rebuild because of constant fires at Coney Island, there never was a shortage of work for McKane’s company.

McKane was successfully working other government angles while doling out deals as Commissioner of the Common Lands. By the late 1870s, McKane had worked his way up to Town Supervisor. The latter was the highest position attainable in Gravesend, the equivalent of a city's mayor. As Town Supervisor, he had to keep a watchful eye on the Tax Department and Department of Licenses. Not to worry, for McKane was in charge of those departments as well. McKane magnanimously also served as Gravesend's Commissioner of Water and Gas and Commissioner of the Board of Health.

While engaged in these thankless government tasks, Citizen McKane was a good family man, went to Methodist Church regularly – he was superintendent of its Sunday School – smoked a cigar once in a while but never drank, or at least nothing stronger than sarsaparilla, though on rare occasions he is known to have gone to hell with himself and indulged in a root beer.

Early in 1884, the courts decided that the town government of Gravesend was empowered to distribute the remaining common lands in the most equable manner favored by the electorate. Some wanted the lands to be sold at public auction. McKane instead suggested having the lands appraised and sold to those holding the leases on them, if they wished to buy them. Of course, this benefitted McKane and his cronies. Lessors were likely to get a good deal on the purchase as the appraisers likely were in McKane’s pocket. In turn, they would continue kicking money back to McKane by giving his construction company the ongoing rebuilding work from fires and storms at Coney Island. So, everyone would win except for a diversified group of land owners, many of whom were absentees. In May, 1884, McKane's proposal was approved in a referendum by the voters of Gravesend and Coney Island, thereby putting an end to the leasing of common lands in favor of outright sale.

Later in 1884, the presidential election was held between Grover Cleveland as the Democratic candidate, and James G. Blaine as the Republican one. In Gravesend and Coney Island, the head of the Democratic Party was John Y. McKane, and the head of the Republican Party was John Y. McKane. McKane talked the situation over with his lieutenants, Kenny Sutherland and Dick Newton. After a meeting with the powers at Tammany Hall, McKane decided to side with them and support Cleveland. Word went out to every hotel, restaurant, bar, tonsorial parlor, clip joint and brothel that McKane expected every man to do his duty and vote a straight Democratic ticket. All voting had to be done in Gravesend's city hall, with different rooms in the building provided for the different election districts. Watchers from both parties were assigned to keep an eye out for voting irregularities, or, as we shall see, perhaps to ensure them.

The national election turned out to be exceptionally close, with the outcome hinging on New York State's electoral vote. Cleveland and Blaine were running neck and neck in New York State. The politicians in Democratic and Republican state and national headquarters were biting their nails as they watched the returns seesaw through the following day. Just when it appeared that there might be a tie vote in New York State, in came the returns from Gravesend. A jubilant roar almost lifted the roof of Tammany Hall. McKane had delivered the vote, several thousand for Cleveland, and barely enough for Blaine to compose a football team. Cleveland won New York by a little more than one-thousand votes. When McKane walked down Surf Avenue after the election, people gaped in awe at the man who had put Cleveland in the White House. McKane and a large delegation of his stalwarts were invited to Cleveland's inauguration. They paraded down Pennsylvania Avenue, and then attended the Inaugural Ball. When they got back to Coney Island, they were greeted like conquering heroes by a large crowd.

In March of 1885, the Republicans struck back at McKane by arresting his brother-in-law, Paul Bauer, for allowing gambling in his West Brighton Hotel. Bauer, who was just a bystander in McKane's political feud, served three months in prison. In 1887, Bauer was committed to a mental institution, where he died two years later. William Engeman's half-brother, George Engeman, was also hauled into court on a bookmaking charge, but the district attorney couldn’t make it stick.

McKane took over the management of Bauer's West Brighton Hotel and Casino while Bauer was in the asylum, and succeeded in paying off Bauer's numerous debts. But McKane found it too enervating to continue managing the properties, so shortly thereafter, in 1888, he leased them for three years to Moritz and Aaron Hertzberg, at $30,000 a year.

McKane at this time may have been too occupied with affairs of state to bother with running a hotel, for it was presidential election time again. The Democratic incumbent, Grover Cleveland, was seeking reelection, and his Republican opponent was Benjamin Harrison. McKane was having some differences with the leaders of the Democratic Party of Brooklyn, and decided to throw his support to the Republicans. Possibly, another reason for backing the Republicans was to placate Brooklyn's blue-bloods, who always seemed to be after his hide. Although Cleveland received a greater popular vote, nationally, Harrison took the electoral vote, and became president. Unlike the previous presidential election, the New York State vote did not decide the outcome of this election.

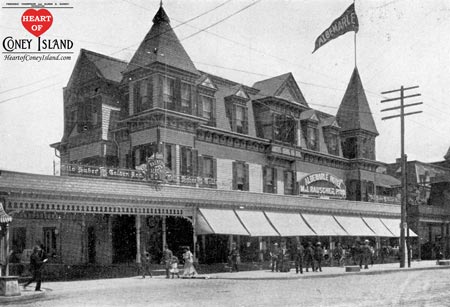

The Albermarle Hotel, McKane's unofficial police headquarters

The Albermarle Hotel, McKane's unofficial police headquarters

Turning to local affairs, McKane decided to further consolidate his position by requesting that the City and State governmental authorities allow Gravesend to have its own police force. Gravesend had a quasi-independent governing body, but its police were provided by the City of Brooklyn and were hence a loose end in McKane’s quest for power. He argued that Coney Island needed police who were specially trained in crowd control, and in the handling of the excessive number of troublemakers and drunks that congregated there. McKane offered to finance this force from the license fees and fines he collected, which could permit the City of Brooklyn to reduce its budget for the Police Department. As nothing pleases politicians more than to be able to show taxpayers that money was being saved, they granted McKane's request. In 1889, the police headquarters of Gravesend was established at the site of the present 60th Police Precinct in West 8th Street, near Surf Avenue. A new firehouse went up alongside it. The unofficial headquarters of Police Chief McKane was Ben Cohen's Albemarle Hotel on Surf Avenue, between West 6th and West 8th Streets. This hotel may have been Paul Bauer's Club House, which stood on the north side of Surf Avenue opposite Bauer's West Brighton Hotel, and about where the Albemarle was situated. Cohen probably leased the Club House and changed its name. McKane liked to sit on a veranda of the Albemarle and keep an eye on the crowd moving along Surf Avenue.

In the spring of 1892, John Y. McKane converted Bauer's Casino into a prize-fighting arena. This aroused the ire of the reform element, who were opposed to that sport because of its brutality and the gambling connected with it. The politicians also opposed the opening of McKane's Coney Island Athletic Club, as it was called, because it drew away business from the fight arenas of Brooklyn and Manhattan, in which they and their gambling friends had financial interests. McKane circumvented this by noting that while prize fighting and gambling were illegal, amateur boxing was not. Officially, all the fights then in New York State were amateur bouts, but the fighters were getting more than medals. Ostensibly, amateur boxing was being presented at the Coney Island Athletic Club solely for the purpose of instructing the viewers in the manly art of self-defense, so that if some street tough, or barroom brawler, sought to intimidate a gentleman, the latter would give a good account of himself. Those paying admission to McKane’s arena were, so to speak, students in a boxing academy learning to protect themselves. It was the same fiction as the one about the purpose of horse racing being to improve the breed.

The year of 1892 had a presidential election, in which Grover Cleveland was again the Democratic candidate against the incumbent, Benjamin Harrison. McKane had backed Cleveland in 1884 and Harrison against him in 1888. Now, having patched up his differences with the Brooklyn Democratic Party leaders, he issued orders to go back to voting for Cleveland. Cleveland had no need of McKane's support this time, however, and was elected by a landslide.

If the Republican reform element of Brooklyn had felt some hesitation about going after McKane because of his previous backing of Harrison, there was nothing to restrain them now. It was open season on McKane for hunters of both parties because of his past actions. He wasn't too concerned because the proprietors and employees in Coney Island were solidly behind him. The farmers of Gravesend had become a minority. The Gravesend dog was now being wagged by its Coney Island tail.

In the autumn of 1893, there were local elections scheduled for such offices as mayor of Brooklyn, and a justice of the New for State Supreme Court. The Republican candidate for mayor was Charles A. Schieren, and for Supreme Court justice, William J. Gaynor. In this particular election, the Boss was backing the Democratic slate. Gaynor, however, had served as a counsel for Gravesend Township and knew how McKane’s political machine operated and took appropriate precautions.

During the registration period, the Republican leaders of Brooklyn sent clerks to copy the names and addresses of the registered voters of Gravesend, so that the supposed voters could be verified independently. When the Brooklyn clerks arrived at the Gravesend Town Hall, they found clerks from the Gravesend Republican Party working on copying the lists. Anson Stratton, a wealthy real estate owner who owed much of his prosperity to McKane, and who was head of Gravesend's Republican Party, had assigned his clerks to their task. The Brooklyn Republican clerks were told that as soon as the local copiers had finished their job, they would turn the lists over to them. The local boys were apparently very slow workers, and finished up on the eve of Election Day.

The night of the eve of the election, several carriages filled with Republican Party officials from Brooklyn arrived at the closed Gravesend Town Hall, where they were confronted by McKane and his police. The newcomers were no ordinary folks, but some of the most socially prominent people of Brooklyn, led by Colonel Alexander S. Bacon. When McKane asked them why they were there, Bacon said that they had come to be watchers for the Republican Party on Election Day. McKane responded that the full quota of watchers had been assigned by the local Republican Party, and directed them to return from where they came. Bacon, producing an injunction, warned McKane that he would be violating the law if he prevented Republican watchers from challenging voters, and from guarding ballot boxes. Famously, McKane replied, “Injunctions don’t go here!” A fracas ensued, with McKane’s police clubbing some of the intruders and arresting them for drunkenness and disorderly conduct. McKane released them from jail after the election.

Despite McKane's efforts on behalf of the Democratic candidates, the Republicans were elected, and they lost no time in dealing with McKane. A grand jury indicted McKane and his confederates for election fraud and assault. Among other infractions, McKane had submitted 2,700 votes when Gravesend only had 1,700 registered voters. McKane and his cronies were tried early in 1894, found guilty, and sentenced to prison.

McKane drew a six-year sentence in Sing Sing, Kenny Sutherland got one year, and Dick Newton, six months. The election commissioners, most of them hotel owners, also got short sentences for having certified to false election registrations. Sutherland fled to Canada, but had a longing for Coney Island, and agreed to return and serve his sentence if no additional time were added. Meanwhile, McKane was released from prison four years later, with time off for good behavior.

By this time, McKane’s West Brighton had eclipsed both Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach as the place to be at Coney Island. Thanks to McKane’s willingness to give anything a try, as long as it could make money, Coney Island was about to undergo its final transformation, from seaside resort to amusements capital of the world.

Upon his return to Coney Island, McKane was greeted warmly by many residents there. When Ben Cohen, who had served time in the chicken coop for having been a Gravesend election commissioner, first spotted McKane on Surf Avenue after his release from Sing Sing, he rushed out of his Albemarle Hotel, embraced the Boss, and insisted he come into his hotel and dine on a sumptuous meal. Old friends arranged banquets and testimonials for McKane. He went into the insurance business, and is said to have sold a policy to Judge Gaynor, so there evidently were no hard feelings between them.

McKane died several months after a stroke in 1899. He was 58 years old and had been out of prison for just one year. The closest family members of his well-attended funeral were his wife, brother, and a blind daughter. Among the pallbearers was Ben Cohen. Whatever faults McKane may have had, he was no religious bigot, unlike some of the so-called ‘respectable’ Brooklynites then. It was charged that several of his patrolmen had prison records. Many of the sheriffs and their deputies in the West then had been gunslingers who had operated on the wrong side of the law, but when a badge was pinned on them, and they found the townspeople regarding them with respect, they developed a sense of pride, and turned out to be among the toughest and best of the lawmen.

After McKane's second in command, Kenny Sutherland, got out of prison, he confined his activities to a hotel that he owned with his brother in Coney Island's Bowery. His civil rights were restored by the governor, whereupon Kenny got a job as clerk of the Coney Island Magistrate Court. He again became active in politics, until May 20, 1910, when he died under the wheels of a train going from Coney Island to his home in Bath Beach. His death was attributed to an accident, but several other political figures of Coney Island died in the same manner, which led to the rumor that they had been slugged on the train and thrown under the wheels. A mix of Tammany and Mafia thugs was moving in about that time, and a decision may have been made to get rid of some old furniture.

This article combines the author's extensive ongoing research with the text of the late Manny Teitelman's unpublished manuscript, 'Coney Island, Last Stop!'

The manuscript's contents are used, modified and published under an exclusive copyright license dated 2016. All rights reserved.

In the spring of 1892, John Y. McKane converted Bauer's Casino into a prize-fighting arena. This aroused the ire of the reform element, who were opposed to that sport because of its brutality and the gambling connected with it. The politicians also opposed the opening of McKane's Coney Island Athletic Club, as it was called, because it drew away business from the fight arenas of Brooklyn and Manhattan, in which they and their gambling friends had financial interests. McKane circumvented this by noting that while prize fighting and gambling were illegal, amateur boxing was not. Officially, all the fights then in New York State were amateur bouts, but the fighters were getting more than medals. Ostensibly, amateur boxing was being presented at the Coney Island Athletic Club solely for the purpose of instructing the viewers in the manly art of self-defense, so that if some street tough, or barroom brawler, sought to intimidate a gentleman, the latter would give a good account of himself. Those paying admission to McKane’s arena were, so to speak, students in a boxing academy learning to protect themselves. It was the same fiction as the one about the purpose of horse racing being to improve the breed.

The year of 1892 had a presidential election, in which Grover Cleveland was again the Democratic candidate against the incumbent, Benjamin Harrison. McKane had backed Cleveland in 1884 and Harrison against him in 1888. Now, having patched up his differences with the Brooklyn Democratic Party leaders, he issued orders to go back to voting for Cleveland. Cleveland had no need of McKane's support this time, however, and was elected by a landslide.

If the Republican reform element of Brooklyn had felt some hesitation about going after McKane because of his previous backing of Harrison, there was nothing to restrain them now. It was open season on McKane for hunters of both parties because of his past actions. He wasn't too concerned because the proprietors and employees in Coney Island were solidly behind him. The farmers of Gravesend had become a minority. The Gravesend dog was now being wagged by its Coney Island tail.

In the autumn of 1893, there were local elections scheduled for such offices as mayor of Brooklyn, and a justice of the New for State Supreme Court. The Republican candidate for mayor was Charles A. Schieren, and for Supreme Court justice, William J. Gaynor. In this particular election, the Boss was backing the Democratic slate. Gaynor, however, had served as a counsel for Gravesend Township and knew how McKane’s political machine operated and took appropriate precautions.

During the registration period, the Republican leaders of Brooklyn sent clerks to copy the names and addresses of the registered voters of Gravesend, so that the supposed voters could be verified independently. When the Brooklyn clerks arrived at the Gravesend Town Hall, they found clerks from the Gravesend Republican Party working on copying the lists. Anson Stratton, a wealthy real estate owner who owed much of his prosperity to McKane, and who was head of Gravesend's Republican Party, had assigned his clerks to their task. The Brooklyn Republican clerks were told that as soon as the local copiers had finished their job, they would turn the lists over to them. The local boys were apparently very slow workers, and finished up on the eve of Election Day.

The night of the eve of the election, several carriages filled with Republican Party officials from Brooklyn arrived at the closed Gravesend Town Hall, where they were confronted by McKane and his police. The newcomers were no ordinary folks, but some of the most socially prominent people of Brooklyn, led by Colonel Alexander S. Bacon. When McKane asked them why they were there, Bacon said that they had come to be watchers for the Republican Party on Election Day. McKane responded that the full quota of watchers had been assigned by the local Republican Party, and directed them to return from where they came. Bacon, producing an injunction, warned McKane that he would be violating the law if he prevented Republican watchers from challenging voters, and from guarding ballot boxes. Famously, McKane replied, “Injunctions don’t go here!” A fracas ensued, with McKane’s police clubbing some of the intruders and arresting them for drunkenness and disorderly conduct. McKane released them from jail after the election.

Despite McKane's efforts on behalf of the Democratic candidates, the Republicans were elected, and they lost no time in dealing with McKane. A grand jury indicted McKane and his confederates for election fraud and assault. Among other infractions, McKane had submitted 2,700 votes when Gravesend only had 1,700 registered voters. McKane and his cronies were tried early in 1894, found guilty, and sentenced to prison.

McKane drew a six-year sentence in Sing Sing, Kenny Sutherland got one year, and Dick Newton, six months. The election commissioners, most of them hotel owners, also got short sentences for having certified to false election registrations. Sutherland fled to Canada, but had a longing for Coney Island, and agreed to return and serve his sentence if no additional time were added. Meanwhile, McKane was released from prison four years later, with time off for good behavior.

By this time, McKane’s West Brighton had eclipsed both Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach as the place to be at Coney Island. Thanks to McKane’s willingness to give anything a try, as long as it could make money, Coney Island was about to undergo its final transformation, from seaside resort to amusements capital of the world.

Upon his return to Coney Island, McKane was greeted warmly by many residents there. When Ben Cohen, who had served time in the chicken coop for having been a Gravesend election commissioner, first spotted McKane on Surf Avenue after his release from Sing Sing, he rushed out of his Albemarle Hotel, embraced the Boss, and insisted he come into his hotel and dine on a sumptuous meal. Old friends arranged banquets and testimonials for McKane. He went into the insurance business, and is said to have sold a policy to Judge Gaynor, so there evidently were no hard feelings between them.

McKane died several months after a stroke in 1899. He was 58 years old and had been out of prison for just one year. The closest family members of his well-attended funeral were his wife, brother, and a blind daughter. Among the pallbearers was Ben Cohen. Whatever faults McKane may have had, he was no religious bigot, unlike some of the so-called ‘respectable’ Brooklynites then. It was charged that several of his patrolmen had prison records. Many of the sheriffs and their deputies in the West then had been gunslingers who had operated on the wrong side of the law, but when a badge was pinned on them, and they found the townspeople regarding them with respect, they developed a sense of pride, and turned out to be among the toughest and best of the lawmen.

After McKane's second in command, Kenny Sutherland, got out of prison, he confined his activities to a hotel that he owned with his brother in Coney Island's Bowery. His civil rights were restored by the governor, whereupon Kenny got a job as clerk of the Coney Island Magistrate Court. He again became active in politics, until May 20, 1910, when he died under the wheels of a train going from Coney Island to his home in Bath Beach. His death was attributed to an accident, but several other political figures of Coney Island died in the same manner, which led to the rumor that they had been slugged on the train and thrown under the wheels. A mix of Tammany and Mafia thugs was moving in about that time, and a decision may have been made to get rid of some old furniture.

This article combines the author's extensive ongoing research with the text of the late Manny Teitelman's unpublished manuscript, 'Coney Island, Last Stop!'

The manuscript's contents are used, modified and published under an exclusive copyright license dated 2016. All rights reserved.

Return to Coney Island History Homepage