Coney Island History: The Rise and Fall of Corbin's Manhattan Beach Resort

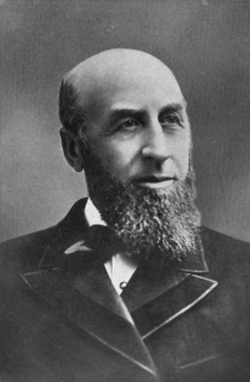

Austin Corbin, one of the few people whose business dealings could make even McKane cringe [2]

Austin Corbin, one of the few people whose business dealings could make even McKane cringe [2]

Austin Corbin's Manhattan Beach Ambitions (c. 1875)

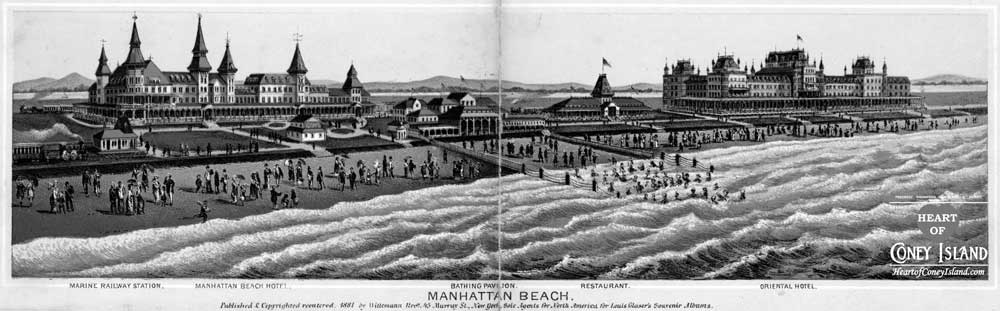

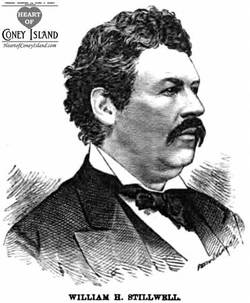

In 1884, William H. Stillwell wrote a history of Coney Island in which he described how the easternmost end of Coney Island, known as Manhattan Beach, had transformed during the prior decade from a collection of sand dunes into a renowned resort area.

According to Stillwell's story, a wealthy banker and railroad magnate by the name of Austin Corbin had a sickly son. A doctor suggested that Coney Island's ocean breezes might help the son's condition. So, around 1875, Corbin brought his wife an son on a trip to the Coney Island House, also known as the Oceanic Hotel. Noting an improvement in his son's health, Corbin decided to stick around and buy some property at the beach.

It all sounds pretty reasonable, right? After all, at the time, with so much pollution in the cities, it was common for doctors to prescribe a trip to the beach for the supposed benefits of breathing in the purer 'ozone' in the air, or to a town like Saratoga Springs, to soak in tubs filled with the town's reputed healing mineral waters.

It turns out that Stillwell was actually re-writing history real-time to suit himself. Corbin's son was no consumptive slum kid who had been deprived of a salubrious environment. Stillwell's story was, at best, only a partial fabrication, and we do not know quite how far he stretched whatever kernel of truth may have existed. Stillwell's Coney Island history wove similarly dubious accounts for other local businessmen and powers that be, such as Paul Bauer's spontaneous decision to acquire the land for his Atlantic Garden Hotel at West Brighton. All of this brown nosing worked out pretty well for Stillwell, who ended up working for Corbin's company and later for Engeman, the developer of neighboring Brighton Beach.

The real story is that in this era, financiers like Corbin were scrambling to form syndicates to exploit real estate and railroad investment opportunities. Corbin had a history of tricking and stealing from just about anyone, legally or otherwise, and was just about as sociopathic as a robber baron could come. He was associated with a group of Boston and London bankers engaged in taking over railroads in the New York area. Plans were underway to extend the Bay Ridge and Jamaica railroad line to Coney Island, and Corbin wanted to build an exclusive resort in Manhattan Beach to cater to well-to-do families that currently traveled to vacation at ritzy out-of-town resorts like Saratoga Springs.

Corbin discussed his plans with one of his acquaintances, Thomas Cable, who ran Cable's Hotel in West Brighton. Cable's view was that the wealthy residents of Brooklyn were unlikely to stay at Corbin's hotel. They might patronize his establishment to the extent of dining there, but they would then get into their carriages and head for home. If Corbin wanted his hotel to prosper, he would have to attract the wealthy residents of Manhattan and elsewhere, who were more likely to check into the hotel, rather than to face the discomfort of a long train and boat ride back home during the night. There might also be a market for affluent out-of-towners to spend their vacations at Manhattan Beach, if it were nice enough.

In 1884, William H. Stillwell wrote a history of Coney Island in which he described how the easternmost end of Coney Island, known as Manhattan Beach, had transformed during the prior decade from a collection of sand dunes into a renowned resort area.

According to Stillwell's story, a wealthy banker and railroad magnate by the name of Austin Corbin had a sickly son. A doctor suggested that Coney Island's ocean breezes might help the son's condition. So, around 1875, Corbin brought his wife an son on a trip to the Coney Island House, also known as the Oceanic Hotel. Noting an improvement in his son's health, Corbin decided to stick around and buy some property at the beach.

It all sounds pretty reasonable, right? After all, at the time, with so much pollution in the cities, it was common for doctors to prescribe a trip to the beach for the supposed benefits of breathing in the purer 'ozone' in the air, or to a town like Saratoga Springs, to soak in tubs filled with the town's reputed healing mineral waters.

It turns out that Stillwell was actually re-writing history real-time to suit himself. Corbin's son was no consumptive slum kid who had been deprived of a salubrious environment. Stillwell's story was, at best, only a partial fabrication, and we do not know quite how far he stretched whatever kernel of truth may have existed. Stillwell's Coney Island history wove similarly dubious accounts for other local businessmen and powers that be, such as Paul Bauer's spontaneous decision to acquire the land for his Atlantic Garden Hotel at West Brighton. All of this brown nosing worked out pretty well for Stillwell, who ended up working for Corbin's company and later for Engeman, the developer of neighboring Brighton Beach.

The real story is that in this era, financiers like Corbin were scrambling to form syndicates to exploit real estate and railroad investment opportunities. Corbin had a history of tricking and stealing from just about anyone, legally or otherwise, and was just about as sociopathic as a robber baron could come. He was associated with a group of Boston and London bankers engaged in taking over railroads in the New York area. Plans were underway to extend the Bay Ridge and Jamaica railroad line to Coney Island, and Corbin wanted to build an exclusive resort in Manhattan Beach to cater to well-to-do families that currently traveled to vacation at ritzy out-of-town resorts like Saratoga Springs.

Corbin discussed his plans with one of his acquaintances, Thomas Cable, who ran Cable's Hotel in West Brighton. Cable's view was that the wealthy residents of Brooklyn were unlikely to stay at Corbin's hotel. They might patronize his establishment to the extent of dining there, but they would then get into their carriages and head for home. If Corbin wanted his hotel to prosper, he would have to attract the wealthy residents of Manhattan and elsewhere, who were more likely to check into the hotel, rather than to face the discomfort of a long train and boat ride back home during the night. There might also be a market for affluent out-of-towners to spend their vacations at Manhattan Beach, if it were nice enough.

William Stillwell: real estate lawyer, McKane henchman, and self-described man of 'unflinching honesty' [1]

William Stillwell: real estate lawyer, McKane henchman, and self-described man of 'unflinching honesty' [1]

Corbin and McKane Hatch a Crooked Plan to Acquire Manhattan Beach

Cable suggested that Corbin talk with Stillwell, who was a real estate lawyer and broker who knew the Coney Island area very well. When Stillwell heard Corbin's elaborate plans for Manhattan Beach, he arranged for Corbin to meet Gravesend's Supervisor, John Y. McKane.

At that private meeting, Corbin told McKane that he wanted to acquire a large tract of land along the beach. McKane asked whether he had any particular tract in mind, to which Corbin replied something along the lines of, 'How about those uninhabited, useless sand dunes and marshes at the east end?' McKane was no dummy himself, and quickly got Corbin to come clean with the full extent of his plans. Corbin disclosed his intention to run a railroad from Jamaica to Sedge Bank (modern-day Manhattan Beach) and to build an exclusive resort on the beach. The resort would have the largest seaside hotel in the world, a large bathing pavilion, restaurants, theatre, and numerous other facilities.

McKane explained the issue with Sedge Bank was that it was still part of the Gravesend common lands, which were held in trust by the Town of Gravesend on behalf of their owners, the descendants of the original thirty-nine Gravesend patentees. The town was supposed to lease the lands for seven years at a time to the highest bidders, with the proceeds being distributed among the owners. McKane was confident that he could arrange for Corbin to lease the land, but Corbin said he would not make such a large investment without owning the land outright. The only land technically available for sale at Sedge Bank was a small section at its west end that had been distributed about a century ago, and whose current owner was looking to unload it.

McKane suggested that he could distribute the Sedge Bank land to the patentees, whereupon Corbin could purchase it from the owners. Corbin objected to the plan as too time-consuming and too costly.

After further thought, Corbin and McKane arrived at a legal, if immoral, solution. They would take the view that technically, it made no difference how the land was distributed, as long as the patentees, or Gravesend Township, derived the benefits of the transaction. In this way, Corbin would be able to purchase all of Manhattan Beach directly from McKane, who was responsible for managing the land. To avoid running a public auction, McKane would hire independent appraisers to value the land in its current state, assuming it remained undeveloped. This would give the land to Corbin at a bargain price. Whether agreed upon directly or simply assumed by McKane, Corbin would understand that the quid pro quo was to hire McKane's personal construction company to build the resort.

Cable suggested that Corbin talk with Stillwell, who was a real estate lawyer and broker who knew the Coney Island area very well. When Stillwell heard Corbin's elaborate plans for Manhattan Beach, he arranged for Corbin to meet Gravesend's Supervisor, John Y. McKane.

At that private meeting, Corbin told McKane that he wanted to acquire a large tract of land along the beach. McKane asked whether he had any particular tract in mind, to which Corbin replied something along the lines of, 'How about those uninhabited, useless sand dunes and marshes at the east end?' McKane was no dummy himself, and quickly got Corbin to come clean with the full extent of his plans. Corbin disclosed his intention to run a railroad from Jamaica to Sedge Bank (modern-day Manhattan Beach) and to build an exclusive resort on the beach. The resort would have the largest seaside hotel in the world, a large bathing pavilion, restaurants, theatre, and numerous other facilities.

McKane explained the issue with Sedge Bank was that it was still part of the Gravesend common lands, which were held in trust by the Town of Gravesend on behalf of their owners, the descendants of the original thirty-nine Gravesend patentees. The town was supposed to lease the lands for seven years at a time to the highest bidders, with the proceeds being distributed among the owners. McKane was confident that he could arrange for Corbin to lease the land, but Corbin said he would not make such a large investment without owning the land outright. The only land technically available for sale at Sedge Bank was a small section at its west end that had been distributed about a century ago, and whose current owner was looking to unload it.

McKane suggested that he could distribute the Sedge Bank land to the patentees, whereupon Corbin could purchase it from the owners. Corbin objected to the plan as too time-consuming and too costly.

After further thought, Corbin and McKane arrived at a legal, if immoral, solution. They would take the view that technically, it made no difference how the land was distributed, as long as the patentees, or Gravesend Township, derived the benefits of the transaction. In this way, Corbin would be able to purchase all of Manhattan Beach directly from McKane, who was responsible for managing the land. To avoid running a public auction, McKane would hire independent appraisers to value the land in its current state, assuming it remained undeveloped. This would give the land to Corbin at a bargain price. Whether agreed upon directly or simply assumed by McKane, Corbin would understand that the quid pro quo was to hire McKane's personal construction company to build the resort.

Corbin and McKane Execute their Crooked Plan (1876-1877)

During the winter of 1876-1877, while the good people of Gravesend were attending to their chores, or snoozing by their fireplaces, Supervisor McKane and his commissioners were quietly disposing of the Sedge Bank to Austin Corbin. During this time, Corbin also acquired, by legitimate means from a private owner, the west end of the Sedge Bank, where he built his Manhattan Hotel. The sales price of the common lands was arrived at by two independent appraisers, one appointed by McKane, the other by Corbin. When Corbin was told the amount, $1,500, he sighed and muttered disconsolately, "Overpriced, but what can I do?" No, dear reader, that amount was not for each acre, but for the whole kit-and-caboodle, comprising about two miles of ocean front, two miles of bay front, and everything between, or over 500 acres, which came to about $3 an acre. From a purchaser's point of view, it was not as good a deal as the one the Dutch had consummated in acquiring Manhattan Island from the Indians, but it was not bad. Whether the 39 patentees got the princely sum of about $40 each from the proceeds, or whether the $1,500 went to pay for town expenses, such as appraiser's fees, is not known. McKane got his Havana cigars, among other things, and Stillwell was put on Corbin's payroll as a consultant, or procurer.

McKane's Corruptness is Finally Revealed... but Too Late

Everyone, including the 39 patentees of record, came to the Sedge Bank and admired Corbin's new Manhattan Beach Hotel, but when Corbin began to expand eastward, the patentees scratched their heads and asked each other whether those weren't Gravesend's common lands that Corbin was moving into. When they finally got around to asking McKane about it, he looked surprised and asked them why they were bringing up a matter that was over a year old. Everyone in town knew that the town's commissioners had sold those useless piles of sand and bogs to Mr. Corbin. To say that the patentees were fit to be tied is to put it mildly. They were so incensed that they called a protest meeting at Gravesend's town hall to be held on December 23, 1878, in order to have McKane nullify the sale to Corbin, and if he refused to do so, they would start a legal action. At a time when all decent folks were decorating their Christmas trees, or doing last minute shopping, these patentee characters, devoid of the holiday spirit, call a protest meeting. As the ordinary citizens of Gravesend saw no reason to concern themselves about the rights of the patentees to get free land, they stayed home. Their place was taken by McKane's musclemen, and by Corbin's railroad goons. McKane and the commissioners showed up to answer questions. One irate patentee declared that the sale of the town's common lands was unprecedented and illegal. McKane agreed that it was unprecedented, but not illegal. The policy of leasing common lands also had been unprecedented, until it was adopted. As for the legal aspect about selling common land, there was nothing in the Dutch grant, nor the English, to indicate how the land was to be distributed. In earlier times, when the town had few expenses, it parceled out free land, but times had changed, and revenue was needed to pay for the expanded public services. The leasing and sale of common lands provided the town with the funds to pay for them.

One obstreperous peasant asked McKane why, if the town was so badly in need of income, he had sold the common lands to Corbin for $1,500 when they were worth closer to $1,500,000. McKane replied that the lands were worth next to nothing if they weren't developed. Mr. Corbin, an eminent gentleman and financier, had gone to great expense to bring in a railroad and erect the largest seaside hotel in the world, and was about to go to even greater expense to develop the east end of the Sedge Bank. This immense summer resort was being placed on the tax rolls to add to the town's income. Also, it was providing many of the town's residents with new Jobs. When these irrefutable arguments failed to still the protests, menacing gestures by tough-looking individuals restored order. A voice vote was then taken to approve of the sale of the entire Sedge Bank to Mr. Corbin, and nary a voice was heard in opposition.

The matter was taken to court, where a decision was rendered that the town's officials acted within their authority to dispose of public lands. If the plaintiffs disapproved of their elected representatives, they should turn them out of office. Turning McKane out of office was like trying to pry a boulder loose with a toothpick. If the plaintiffs had any proof of election irregularities by McKane, they should submit it to the district attorney, or attorney general.

No Honor Among Thieves

Alas, it must be told that not only is there no honor among thieves, but very little appreciation. After all McKane did for him, Corbin brought in outside contractors for the building of his huge establishment. The McKane Construction Company didn't even get a contract to erect the few privies around the grounds. What McKane had to say about this cannot be quoted, as it surely would consist entirely of expletives which must be deleted. However, the reader should be happy to learn that McKane and Corbin eventually reconciled. In fact, when McKane was being tried for stuffing ballot boxes, for which he received a stretch in Sing Sing, Corbin appeared as a character witness for him. It would have been appropriate for the court to ask Corbin to have produced a character witness for himself.

During the winter of 1876-1877, while the good people of Gravesend were attending to their chores, or snoozing by their fireplaces, Supervisor McKane and his commissioners were quietly disposing of the Sedge Bank to Austin Corbin. During this time, Corbin also acquired, by legitimate means from a private owner, the west end of the Sedge Bank, where he built his Manhattan Hotel. The sales price of the common lands was arrived at by two independent appraisers, one appointed by McKane, the other by Corbin. When Corbin was told the amount, $1,500, he sighed and muttered disconsolately, "Overpriced, but what can I do?" No, dear reader, that amount was not for each acre, but for the whole kit-and-caboodle, comprising about two miles of ocean front, two miles of bay front, and everything between, or over 500 acres, which came to about $3 an acre. From a purchaser's point of view, it was not as good a deal as the one the Dutch had consummated in acquiring Manhattan Island from the Indians, but it was not bad. Whether the 39 patentees got the princely sum of about $40 each from the proceeds, or whether the $1,500 went to pay for town expenses, such as appraiser's fees, is not known. McKane got his Havana cigars, among other things, and Stillwell was put on Corbin's payroll as a consultant, or procurer.

McKane's Corruptness is Finally Revealed... but Too Late

Everyone, including the 39 patentees of record, came to the Sedge Bank and admired Corbin's new Manhattan Beach Hotel, but when Corbin began to expand eastward, the patentees scratched their heads and asked each other whether those weren't Gravesend's common lands that Corbin was moving into. When they finally got around to asking McKane about it, he looked surprised and asked them why they were bringing up a matter that was over a year old. Everyone in town knew that the town's commissioners had sold those useless piles of sand and bogs to Mr. Corbin. To say that the patentees were fit to be tied is to put it mildly. They were so incensed that they called a protest meeting at Gravesend's town hall to be held on December 23, 1878, in order to have McKane nullify the sale to Corbin, and if he refused to do so, they would start a legal action. At a time when all decent folks were decorating their Christmas trees, or doing last minute shopping, these patentee characters, devoid of the holiday spirit, call a protest meeting. As the ordinary citizens of Gravesend saw no reason to concern themselves about the rights of the patentees to get free land, they stayed home. Their place was taken by McKane's musclemen, and by Corbin's railroad goons. McKane and the commissioners showed up to answer questions. One irate patentee declared that the sale of the town's common lands was unprecedented and illegal. McKane agreed that it was unprecedented, but not illegal. The policy of leasing common lands also had been unprecedented, until it was adopted. As for the legal aspect about selling common land, there was nothing in the Dutch grant, nor the English, to indicate how the land was to be distributed. In earlier times, when the town had few expenses, it parceled out free land, but times had changed, and revenue was needed to pay for the expanded public services. The leasing and sale of common lands provided the town with the funds to pay for them.

One obstreperous peasant asked McKane why, if the town was so badly in need of income, he had sold the common lands to Corbin for $1,500 when they were worth closer to $1,500,000. McKane replied that the lands were worth next to nothing if they weren't developed. Mr. Corbin, an eminent gentleman and financier, had gone to great expense to bring in a railroad and erect the largest seaside hotel in the world, and was about to go to even greater expense to develop the east end of the Sedge Bank. This immense summer resort was being placed on the tax rolls to add to the town's income. Also, it was providing many of the town's residents with new Jobs. When these irrefutable arguments failed to still the protests, menacing gestures by tough-looking individuals restored order. A voice vote was then taken to approve of the sale of the entire Sedge Bank to Mr. Corbin, and nary a voice was heard in opposition.

The matter was taken to court, where a decision was rendered that the town's officials acted within their authority to dispose of public lands. If the plaintiffs disapproved of their elected representatives, they should turn them out of office. Turning McKane out of office was like trying to pry a boulder loose with a toothpick. If the plaintiffs had any proof of election irregularities by McKane, they should submit it to the district attorney, or attorney general.

No Honor Among Thieves

Alas, it must be told that not only is there no honor among thieves, but very little appreciation. After all McKane did for him, Corbin brought in outside contractors for the building of his huge establishment. The McKane Construction Company didn't even get a contract to erect the few privies around the grounds. What McKane had to say about this cannot be quoted, as it surely would consist entirely of expletives which must be deleted. However, the reader should be happy to learn that McKane and Corbin eventually reconciled. In fact, when McKane was being tried for stuffing ballot boxes, for which he received a stretch in Sing Sing, Corbin appeared as a character witness for him. It would have been appropriate for the court to ask Corbin to have produced a character witness for himself.

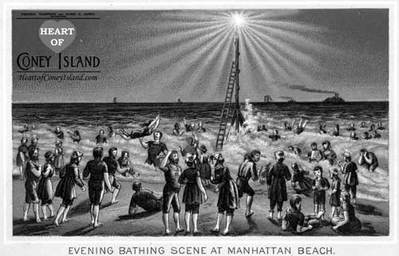

'Night bathing' at Manhattan Beach was all the rage.

'Night bathing' at Manhattan Beach was all the rage.

Corbin's Manhattan Beach Resort (1877)

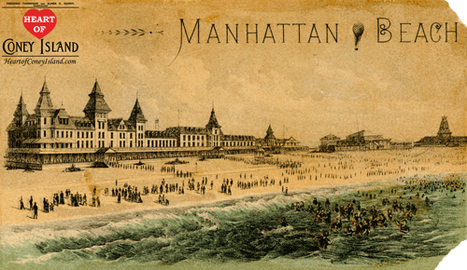

Notwithstanding Corbin's shady methods, he built an impressive resort, which he called Manhattan Beach, in an obvious attempt to attract Manhattan's high-society nabobs to his establishment. It first opened to an immense crowd on July 4, 1877.

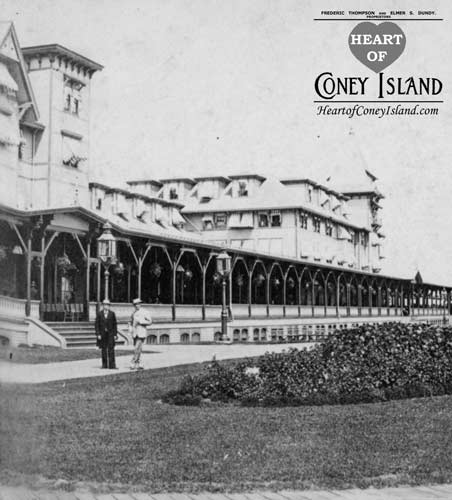

Manhattan Beach Hotel

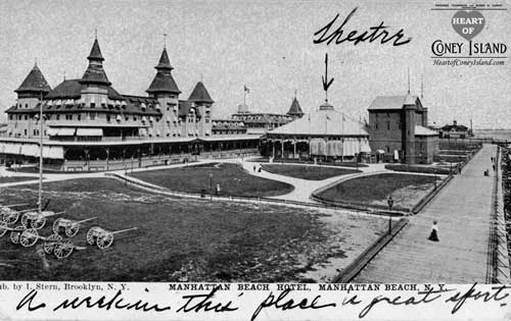

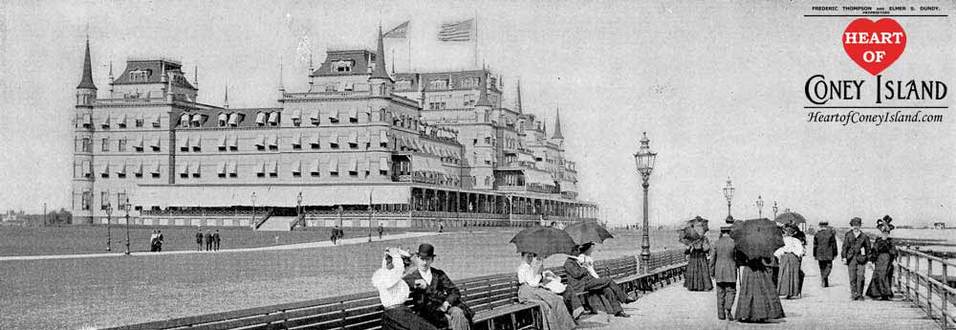

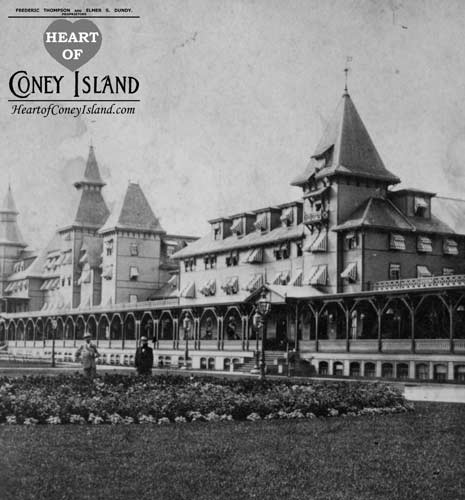

The all-wooden Manhattan Beach Hotel was situated between the present Amherst and Coleridge Streets. The front of the building was about four hundred feet from the surf, and its rear was close to the present Oriental Boulevard.

The hotel had an ocean frontage of 660 feet, was from three to four stories in height, and had 300 guest rooms, all with private baths. There was elevator service to the upper floors, and at each landing a guard sat at a desk to prevent unauthorized persons from entering the corridor. A wide veranda extended along the front and sides of the main floor. The upper story had verandas in front of special suites reserved for important guests. Two restaurants on the main floor and sections of the veranda could accommodate four thousand diners at one time. There was a sizable bar, as well as the usual amenities found in first class hotels.

In front of the entrance was a bandstand where Patrick Sarsfield Gilmore conducted his fifty-piece 22nd Regimental Band. Paved walks amid lawns and flower beds extended southward to an embankment, where several steps led down to the beach.

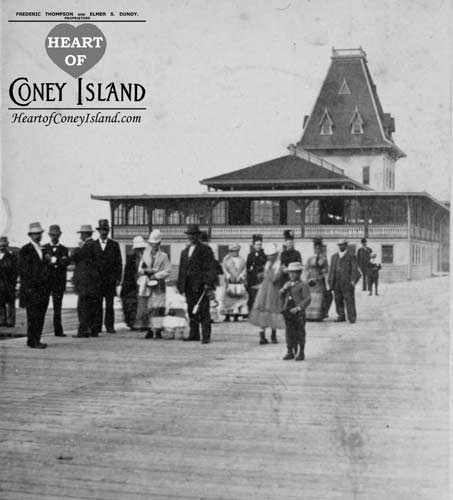

Bathing Pavilion

East of the Manhattan Hotel, from the present Ocean Avenue to Falmouth Street, was a three story brick-and-frame bathing pavilion, having a frontage of 520 feet, and a depth of 170 feet. It had lockers to accommodate 2,200 men and 800 women, bathers at one time. There were 12,000 bathing suits available for rental, and seasonal lockers for those who preferred to use their own suits. Invalids had indoor facilities for hot salt-water baths. For those desiring to bathe in the evening, there were electric lights illuminating the beach. Lifelines extended out into the surf and a raft was anchored off shore. Life guards in catamarans kept watchful eyes on swimmers during authorized bathing hours. The bathing pavilion was enclosed by an amphitheater in which non-bathers could sit – for an admission charge – and observe those in the surf, while listening to music being played on a nearby bandstand.

Dining Pavilion

East of the bathing amphitheater was a dining pavilion, which had served as the Brazilian Pavilion at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. This building, also known as the Restaurant, and as the Grand Pavilion, could accommodate 1,500 diners who had a taste for clambakes. It had waiter service for those who desired it, and special tables for those who did not. Food and liquid refreshments could be obtained at bars. The pavilion also had facilities for outdoor dining by picnic parties. According to one account, this area was patronized to some extent by German and Jewish immigrants, with their frauen und kinder.

Hot Air Balloon Ride

In the rear of the Manhattan Hotel, that is, north of the present Oriental Boulevard was a large enclosure for a balloon, which could carry passengers, for five dollars each, to a height of a quarter of a mile, after which it would be drawn back to the ground by a cable. A small plant was nearby to produce gas for the balloon.

Notwithstanding Corbin's shady methods, he built an impressive resort, which he called Manhattan Beach, in an obvious attempt to attract Manhattan's high-society nabobs to his establishment. It first opened to an immense crowd on July 4, 1877.

Manhattan Beach Hotel

The all-wooden Manhattan Beach Hotel was situated between the present Amherst and Coleridge Streets. The front of the building was about four hundred feet from the surf, and its rear was close to the present Oriental Boulevard.

The hotel had an ocean frontage of 660 feet, was from three to four stories in height, and had 300 guest rooms, all with private baths. There was elevator service to the upper floors, and at each landing a guard sat at a desk to prevent unauthorized persons from entering the corridor. A wide veranda extended along the front and sides of the main floor. The upper story had verandas in front of special suites reserved for important guests. Two restaurants on the main floor and sections of the veranda could accommodate four thousand diners at one time. There was a sizable bar, as well as the usual amenities found in first class hotels.

In front of the entrance was a bandstand where Patrick Sarsfield Gilmore conducted his fifty-piece 22nd Regimental Band. Paved walks amid lawns and flower beds extended southward to an embankment, where several steps led down to the beach.

Bathing Pavilion

East of the Manhattan Hotel, from the present Ocean Avenue to Falmouth Street, was a three story brick-and-frame bathing pavilion, having a frontage of 520 feet, and a depth of 170 feet. It had lockers to accommodate 2,200 men and 800 women, bathers at one time. There were 12,000 bathing suits available for rental, and seasonal lockers for those who preferred to use their own suits. Invalids had indoor facilities for hot salt-water baths. For those desiring to bathe in the evening, there were electric lights illuminating the beach. Lifelines extended out into the surf and a raft was anchored off shore. Life guards in catamarans kept watchful eyes on swimmers during authorized bathing hours. The bathing pavilion was enclosed by an amphitheater in which non-bathers could sit – for an admission charge – and observe those in the surf, while listening to music being played on a nearby bandstand.

Dining Pavilion

East of the bathing amphitheater was a dining pavilion, which had served as the Brazilian Pavilion at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. This building, also known as the Restaurant, and as the Grand Pavilion, could accommodate 1,500 diners who had a taste for clambakes. It had waiter service for those who desired it, and special tables for those who did not. Food and liquid refreshments could be obtained at bars. The pavilion also had facilities for outdoor dining by picnic parties. According to one account, this area was patronized to some extent by German and Jewish immigrants, with their frauen und kinder.

Hot Air Balloon Ride

In the rear of the Manhattan Hotel, that is, north of the present Oriental Boulevard was a large enclosure for a balloon, which could carry passengers, for five dollars each, to a height of a quarter of a mile, after which it would be drawn back to the ground by a cable. A small plant was nearby to produce gas for the balloon.

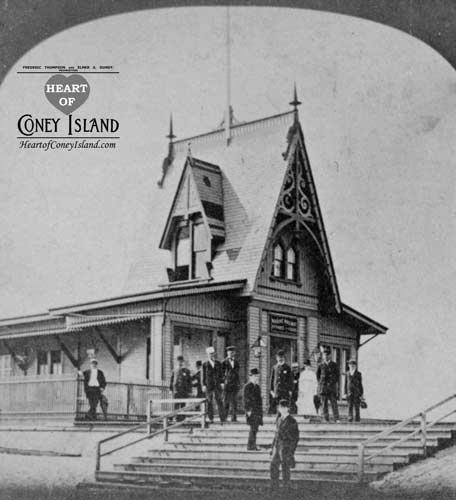

The Marine Railway

Along what is now Oriental Boulevard, Corbin built a narrow gauge, single track line called the Marine Railroad, or Marine Railway. It ran between the present Gerald H. Chambers Square, at the west end of Oriental Boulevard, and Point Breeze Hotel, at the east end of Manhattan Beach. The east end at the time was further east than it is now, and it included Pelican Island, which is now under water. Another section of the Marine Railway served as a shuttle, about a half-mile in length, between the Manhattan and Brighton Beach Hotels.

Point Breeze Hotel

Corbin constructed his Point Breeze Hotel and a wooden pier nearby to accommodate yachtsmen and fishermen. He also had another project in mind, a very exclusive hotel where important people and multi-millionaires could bring their families to stay for the season. They would be close to the financial marts of the city, while having all the advantages of a Newport or Saratoga. A group of millionaire sportsmen had already begun to construct a racetrack in the nearby Sheepshead Bay area to rival anything Saratoga had to offer. However, places like Newport and Saratoga had an advantage lacking at Coney Island, namely, the absence of poor folks, to which many of the affluent and fashionable were allergic. This didn't faze Austin Corbin. He knew his way around.

Along what is now Oriental Boulevard, Corbin built a narrow gauge, single track line called the Marine Railroad, or Marine Railway. It ran between the present Gerald H. Chambers Square, at the west end of Oriental Boulevard, and Point Breeze Hotel, at the east end of Manhattan Beach. The east end at the time was further east than it is now, and it included Pelican Island, which is now under water. Another section of the Marine Railway served as a shuttle, about a half-mile in length, between the Manhattan and Brighton Beach Hotels.

Point Breeze Hotel

Corbin constructed his Point Breeze Hotel and a wooden pier nearby to accommodate yachtsmen and fishermen. He also had another project in mind, a very exclusive hotel where important people and multi-millionaires could bring their families to stay for the season. They would be close to the financial marts of the city, while having all the advantages of a Newport or Saratoga. A group of millionaire sportsmen had already begun to construct a racetrack in the nearby Sheepshead Bay area to rival anything Saratoga had to offer. However, places like Newport and Saratoga had an advantage lacking at Coney Island, namely, the absence of poor folks, to which many of the affluent and fashionable were allergic. This didn't faze Austin Corbin. He knew his way around.

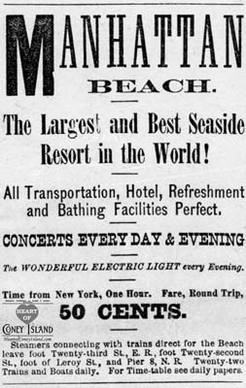

An 1878 ad for Manhattan Beach Resort

An 1878 ad for Manhattan Beach Resort

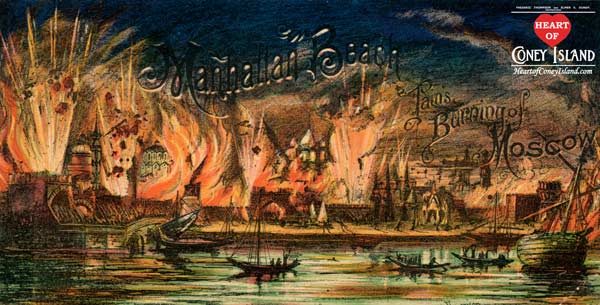

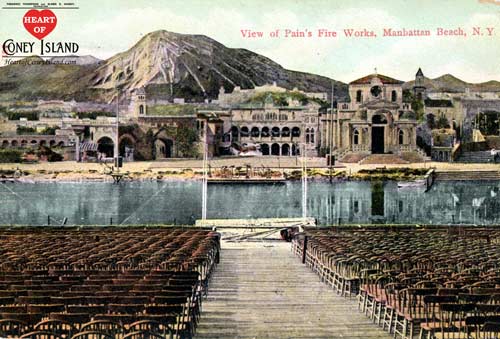

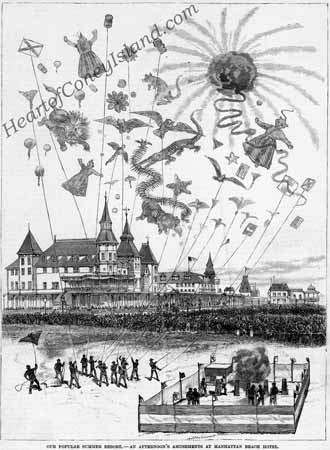

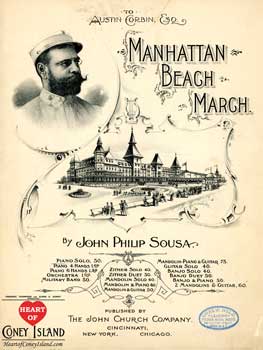

Pain’s Fireworks Shows

North of the dining pavilion was a huge stadium, or outdoor theatre, where pyrotechnical shows were presented by James Pain, an English fireworks manufacturer with a flair for show business. Pain first presented his unique spectacles in London's Crystal Palace, where they became immensely popular. His subjects were representations of historical events or natural disasters, culminating in a grand fireworks display. This marvelous showman presented a blend of pageantry, drama, and pyrotechnics. He understood that a mere fireworks show could achieve a greater dimension by the addition of a story line and characterization.

In 1877, he came to New York with his son, Henry J., then in his late twenties, to present his extravaganzas at Manhattan Beach. Their first show at Manhattan Beach took place shortly after July Fourth of 1879. After seven years, James Pain returned to England, leaving his son to carry on his work at Coney Island. Henry J. Pain remained at Coney Island until 1910. For the complete story of Pain's incredible shows, see the Pain's Fireworks article.

Corbin Adopts an Anti-Semitic ‘Marketing Strategy’

Several years earlier, Judge Hilton, who owned a Saratoga hotel, decided to advertise the exclusiveness of his establishment by publicly attacking the Jews and declaring that he would turn them away if they tried to check in at his hotel. Few, if any, had ever sought to enter the hotel, but that didn't matter. The Jew was a convenient whipping boy to make the non-Jew feel important.

Corbin decided to do a Hilton, On July 21, 1879, he invited a reporter of the New York Daily Herald to his office. Present also was Austin's brother, Daniel Chase Corbin, who is described in the Dictionary of American Biography as ‘irritable and brusque’. The following day, the newspaper ran an account of the interview, in which the Corbins assailed the Jews for being offensive in their ways, and always demanding too much for their money. Henceforth, they would not be welcome at Manhattan Beach. Corbin could now proceed to build his ornate Oriental Hotel.

Corbin's unprovoked insult caused a furor in New York. Some called for mass demonstrations at Manhattan Beach, and some threatened to take legal action against Corbin by invoking Chapter 114 of the United States Civil Rights Act of 1875, which prohibited discrimination in places of public accommodation. However, calmer heads prevailed among the Jews, who were urged to treat boors like Corbin with contempt, and to show their self-respect by staying away from where they were not wanted.

The press and Christian clergy were almost unanimous in their condemnation of Corbin. The New York Commercial Advertizer wrote on July 23, 1879: 'Mr. Corbin chose to go out of his way to abuse a large class of people who are no better and no worse than any other.... If he should try to exclude Jews from his hotel, he could not succeed any better than if he had made war on the Irish, the German, the Scot, or any other people who might have happened to arouse his spleen or touch his prejudice'. Another wrote that if Corbin wished to purge his hotel of impurities, he might start by excluding his elderly Wall Street friends who checked in with their young chorus girls.

Reverend R. S. McArthur, in his Sunday sermon of July, 27, 1879, at the Calvary Church, 23rd Street, New York, stated that, 'the Jew is anathematized and insulted, and yet he is one of the most distinguished and respectable of foreigners. We find him in the busy marts of trade, in law, art, science and literature, and but seldom in jails, courts or institutions for the vicious....' Reverend Dr. Justin D. Fulton, in a Sunday sermon at his Baptist Church in Brooklyn, said, 'The persecution of the Jews will not be a paying investment. The hotel proprietor may desire to cater to men who, apart from their families, drink and revel, and may treat with disdain the men who are temperate, and who go with their families for recreation, and refuse to spend great sums in drink....' And Reverend Alfred H. Moment, of the Spring Street Presbyterian Church, in his Sunday sermon of July 27th, declared that Corbin had attacked a law abiding people who had 'fewer murderers, fewer fallen women among them, than did other people.'

Among the other hotel owners in Coney Island, only Vanderveer supported Corbin. Paul Bauer referred to Corbin's action as 'an advertising dodge'. Most of them declared that all persons who behaved themselves were welcome in their establishments. Anti-Semitism was nothing new in the United States, but it was usually expressed in a covert manner, rather than openly, as in Europe. Anyone with a Jewish sounding name filling out a reservation slip at the check-in desk of a swanky hotel could expect to hear the stock response, "I'm sorry, but we're all filled up.” Many a German “Bloom” withered on the vine because of being mistaken for a Jewish one. There is the case of the noted entertainer, George M. Cohan, who tried to register at a plush hotel, and was told by the reception manager, who failed to recognize him, that there were no rooms available. An alert desk clerk whispered to the manager that the great George M, Cohan, a Christian, had been turned away. The manager rushed to the door, informed Cohan that there had been a mistake, and that he had several excellent suites available, to which Cohan replied, 'It seems that we both made a mistake. You mistook me for a Jew, and I mistook you for a gentleman'. With that, Cohan left the premises.

While the Corbin-Jewish controversy was going on, the main attraction at the Manhattan Beach bandstand was the world famous cornetist, Jules Levy, which must have puzzled the patrons there. Levy backed Corbin, insisting that he only opposed those who were alien in appearance and unrefined in their manners. Levy soon found himself ostracized by his co-religionists.

North of the dining pavilion was a huge stadium, or outdoor theatre, where pyrotechnical shows were presented by James Pain, an English fireworks manufacturer with a flair for show business. Pain first presented his unique spectacles in London's Crystal Palace, where they became immensely popular. His subjects were representations of historical events or natural disasters, culminating in a grand fireworks display. This marvelous showman presented a blend of pageantry, drama, and pyrotechnics. He understood that a mere fireworks show could achieve a greater dimension by the addition of a story line and characterization.

In 1877, he came to New York with his son, Henry J., then in his late twenties, to present his extravaganzas at Manhattan Beach. Their first show at Manhattan Beach took place shortly after July Fourth of 1879. After seven years, James Pain returned to England, leaving his son to carry on his work at Coney Island. Henry J. Pain remained at Coney Island until 1910. For the complete story of Pain's incredible shows, see the Pain's Fireworks article.

Corbin Adopts an Anti-Semitic ‘Marketing Strategy’

Several years earlier, Judge Hilton, who owned a Saratoga hotel, decided to advertise the exclusiveness of his establishment by publicly attacking the Jews and declaring that he would turn them away if they tried to check in at his hotel. Few, if any, had ever sought to enter the hotel, but that didn't matter. The Jew was a convenient whipping boy to make the non-Jew feel important.

Corbin decided to do a Hilton, On July 21, 1879, he invited a reporter of the New York Daily Herald to his office. Present also was Austin's brother, Daniel Chase Corbin, who is described in the Dictionary of American Biography as ‘irritable and brusque’. The following day, the newspaper ran an account of the interview, in which the Corbins assailed the Jews for being offensive in their ways, and always demanding too much for their money. Henceforth, they would not be welcome at Manhattan Beach. Corbin could now proceed to build his ornate Oriental Hotel.

Corbin's unprovoked insult caused a furor in New York. Some called for mass demonstrations at Manhattan Beach, and some threatened to take legal action against Corbin by invoking Chapter 114 of the United States Civil Rights Act of 1875, which prohibited discrimination in places of public accommodation. However, calmer heads prevailed among the Jews, who were urged to treat boors like Corbin with contempt, and to show their self-respect by staying away from where they were not wanted.

The press and Christian clergy were almost unanimous in their condemnation of Corbin. The New York Commercial Advertizer wrote on July 23, 1879: 'Mr. Corbin chose to go out of his way to abuse a large class of people who are no better and no worse than any other.... If he should try to exclude Jews from his hotel, he could not succeed any better than if he had made war on the Irish, the German, the Scot, or any other people who might have happened to arouse his spleen or touch his prejudice'. Another wrote that if Corbin wished to purge his hotel of impurities, he might start by excluding his elderly Wall Street friends who checked in with their young chorus girls.

Reverend R. S. McArthur, in his Sunday sermon of July, 27, 1879, at the Calvary Church, 23rd Street, New York, stated that, 'the Jew is anathematized and insulted, and yet he is one of the most distinguished and respectable of foreigners. We find him in the busy marts of trade, in law, art, science and literature, and but seldom in jails, courts or institutions for the vicious....' Reverend Dr. Justin D. Fulton, in a Sunday sermon at his Baptist Church in Brooklyn, said, 'The persecution of the Jews will not be a paying investment. The hotel proprietor may desire to cater to men who, apart from their families, drink and revel, and may treat with disdain the men who are temperate, and who go with their families for recreation, and refuse to spend great sums in drink....' And Reverend Alfred H. Moment, of the Spring Street Presbyterian Church, in his Sunday sermon of July 27th, declared that Corbin had attacked a law abiding people who had 'fewer murderers, fewer fallen women among them, than did other people.'

Among the other hotel owners in Coney Island, only Vanderveer supported Corbin. Paul Bauer referred to Corbin's action as 'an advertising dodge'. Most of them declared that all persons who behaved themselves were welcome in their establishments. Anti-Semitism was nothing new in the United States, but it was usually expressed in a covert manner, rather than openly, as in Europe. Anyone with a Jewish sounding name filling out a reservation slip at the check-in desk of a swanky hotel could expect to hear the stock response, "I'm sorry, but we're all filled up.” Many a German “Bloom” withered on the vine because of being mistaken for a Jewish one. There is the case of the noted entertainer, George M. Cohan, who tried to register at a plush hotel, and was told by the reception manager, who failed to recognize him, that there were no rooms available. An alert desk clerk whispered to the manager that the great George M, Cohan, a Christian, had been turned away. The manager rushed to the door, informed Cohan that there had been a mistake, and that he had several excellent suites available, to which Cohan replied, 'It seems that we both made a mistake. You mistook me for a Jew, and I mistook you for a gentleman'. With that, Cohan left the premises.

While the Corbin-Jewish controversy was going on, the main attraction at the Manhattan Beach bandstand was the world famous cornetist, Jules Levy, which must have puzzled the patrons there. Levy backed Corbin, insisting that he only opposed those who were alien in appearance and unrefined in their manners. Levy soon found himself ostracized by his co-religionists.

Manhattan Beach Hotel and grounds

Manhattan Beach Hotel and grounds

A Memorable Evening at the Manhattan Beach Hotel (1880)

With Corbin's 'No Jews Allowed' policy in force, one would expect only serenity and bliss at Manhattan Beach. It was certainly not so on the night of April 30, 1880, though it started out that way. The weather was mild, and many people had come to view Corbin's new hotel, the Oriental, due to open in July. Corbin had decided to open the Manhattan Beach Hotel early, before the Brighton Hotel did. At the conclusion of a band concert, thousands of people crowded into the dining room, while many others awaited their turn to dine by forming a line that extended out onto the veranda and down to the lawn. It was a good-natured, hungry crowd. The kitchen was well stocked with victuals, and the scent of cooking food permeated to the end of the line. There was a slight problem, however, as Corbin had decided to economize on waiters. A half an hour slid by, and the line hadn't moved. Some left the line for the bar, returning with schooners of beer for their friends, which sharpened their appetites for the coming feast. Another half an hour, and still no movement of the line. People who had had the foresight to dine while the band was playing outside were waving for their bills to the overworked waiters, who were going at full speed around corners on one foot, like Charlie Chaplin. People waited endlessly for the waiter to take their orders, waited endlessly for the orders to be delivered, and took a little time to eat after the food arrived. The poor waiters were careening around tables with trays, being abused from all sides, which occasionally caused a tray heaped with food to end up on the floor. Some diners, who had finished their meals, were dawdling over empty coffee cups, engaged interminably in their inane, chatter, without any consideration for those waiting to be seated, if not served. Nasty people, probably converted Jews. By the end of the second hour, some on the line had surmised that they were involved in was a lost cause. Genteel ladies began to feel faint from hunger, and their furious escorts vented their frustration by giving the veranda's rail whacks with their canes, perhaps visualizing the rail as an extension of Corbin's skull. Then, suddenly, amid the growing tumult of the famished crowd, a bell sounded, like a peal of doom. The signal for the last train back to the city! Pandemonium! The 9:00 p.m. train would be leaving in five minutes. People who had eaten but were unable to get a waiter to pay their checks, fled to the train, joined by those partly through their meals, and by those seated and waiting to be served. Waiters became frantic, not because the checks were unpaid, but because the tips were unpaid. Those who had stood on line for hours rushed into the dining room, forgot their brooding, scooped up morsels of food from the tables, and dashed for the train. It was like a defeated army fleeing in a rout. Not all fled, some surrendering to the enemy because they were too weak to run. There were a few ladies who were so hungry and upset that they just sat down and wept. Most of the several hundred people who remained were more philosophical, and reasoned that with the departure of the folks on the train, those remaining would be properly served. After they had eaten and could think more clearly, they would figure out how to get back to town. Word began to circulate that the last train out of the Culver Line station at West Brighton was 11:00 p.m. Plenty of time.

One might ask why Corbin didn't delay the departure of his last train until everyone had been served in his dining room. Rumor had it that the waiter shortage had been deliberate, so that many of the diners would have to check into the hotel for the night. A few did, but the others, after finishing their meals, set out on Toot for West Brighton, over a mile to the west. In the daytime, this would not have presented a problem, except that the ladies would have had to remove their fancy shoes to trudge through the sand, but it was night, cloudy and pitch dark. The Brighton Hotel was still closed, and the Marine Railroad to it from Manhattan Beach was not running. Many followed the tracks, tripping over ties or rails, and falling. Some tripped over driftwood, or toppled into holes in the sand. A few tried to improvise torches, but the wind blew out the flames. The distant light from West Brighton was all that the long, straggling, reeling line of sufferers had to guide it. Women finally arriving at Culver Plaza were bawling, bruised from falls, their clothes soiled, torn, and in disarray. Their male companions cursed Corbin, and swore never to set foot in Manhattan Beach again. One indignant gentleman, riding home on a Culver train, was quoted as saying that Corbin might have had the decency to have excluded non-Jews as well as Jews from Manhattan Beach.

Perhaps the gentleman was being unfair to Mr. Corbin. After all, he was building a resort for the millionaires, not for the millions. If people lacked the means to check into his ornate establishment, it was not his fault. They had only themselves to blame for their poverty.

With Corbin's 'No Jews Allowed' policy in force, one would expect only serenity and bliss at Manhattan Beach. It was certainly not so on the night of April 30, 1880, though it started out that way. The weather was mild, and many people had come to view Corbin's new hotel, the Oriental, due to open in July. Corbin had decided to open the Manhattan Beach Hotel early, before the Brighton Hotel did. At the conclusion of a band concert, thousands of people crowded into the dining room, while many others awaited their turn to dine by forming a line that extended out onto the veranda and down to the lawn. It was a good-natured, hungry crowd. The kitchen was well stocked with victuals, and the scent of cooking food permeated to the end of the line. There was a slight problem, however, as Corbin had decided to economize on waiters. A half an hour slid by, and the line hadn't moved. Some left the line for the bar, returning with schooners of beer for their friends, which sharpened their appetites for the coming feast. Another half an hour, and still no movement of the line. People who had had the foresight to dine while the band was playing outside were waving for their bills to the overworked waiters, who were going at full speed around corners on one foot, like Charlie Chaplin. People waited endlessly for the waiter to take their orders, waited endlessly for the orders to be delivered, and took a little time to eat after the food arrived. The poor waiters were careening around tables with trays, being abused from all sides, which occasionally caused a tray heaped with food to end up on the floor. Some diners, who had finished their meals, were dawdling over empty coffee cups, engaged interminably in their inane, chatter, without any consideration for those waiting to be seated, if not served. Nasty people, probably converted Jews. By the end of the second hour, some on the line had surmised that they were involved in was a lost cause. Genteel ladies began to feel faint from hunger, and their furious escorts vented their frustration by giving the veranda's rail whacks with their canes, perhaps visualizing the rail as an extension of Corbin's skull. Then, suddenly, amid the growing tumult of the famished crowd, a bell sounded, like a peal of doom. The signal for the last train back to the city! Pandemonium! The 9:00 p.m. train would be leaving in five minutes. People who had eaten but were unable to get a waiter to pay their checks, fled to the train, joined by those partly through their meals, and by those seated and waiting to be served. Waiters became frantic, not because the checks were unpaid, but because the tips were unpaid. Those who had stood on line for hours rushed into the dining room, forgot their brooding, scooped up morsels of food from the tables, and dashed for the train. It was like a defeated army fleeing in a rout. Not all fled, some surrendering to the enemy because they were too weak to run. There were a few ladies who were so hungry and upset that they just sat down and wept. Most of the several hundred people who remained were more philosophical, and reasoned that with the departure of the folks on the train, those remaining would be properly served. After they had eaten and could think more clearly, they would figure out how to get back to town. Word began to circulate that the last train out of the Culver Line station at West Brighton was 11:00 p.m. Plenty of time.

One might ask why Corbin didn't delay the departure of his last train until everyone had been served in his dining room. Rumor had it that the waiter shortage had been deliberate, so that many of the diners would have to check into the hotel for the night. A few did, but the others, after finishing their meals, set out on Toot for West Brighton, over a mile to the west. In the daytime, this would not have presented a problem, except that the ladies would have had to remove their fancy shoes to trudge through the sand, but it was night, cloudy and pitch dark. The Brighton Hotel was still closed, and the Marine Railroad to it from Manhattan Beach was not running. Many followed the tracks, tripping over ties or rails, and falling. Some tripped over driftwood, or toppled into holes in the sand. A few tried to improvise torches, but the wind blew out the flames. The distant light from West Brighton was all that the long, straggling, reeling line of sufferers had to guide it. Women finally arriving at Culver Plaza were bawling, bruised from falls, their clothes soiled, torn, and in disarray. Their male companions cursed Corbin, and swore never to set foot in Manhattan Beach again. One indignant gentleman, riding home on a Culver train, was quoted as saying that Corbin might have had the decency to have excluded non-Jews as well as Jews from Manhattan Beach.

Perhaps the gentleman was being unfair to Mr. Corbin. After all, he was building a resort for the millionaires, not for the millions. If people lacked the means to check into his ornate establishment, it was not his fault. They had only themselves to blame for their poverty.

The Oriental Hotel (1880)

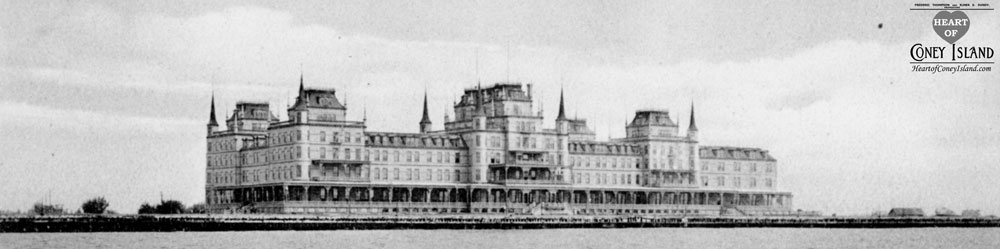

On July 4, 1880, Corbin opened his new Oriental Hotel. This palacial resort was approximately two hundred yards east of the Picnic Pavilion, or roughly one thousand yards east of the Manhattan Hotel. The Oriental was Coney Island's flagship hotel and was one of the most technologically sophisticated and refined resorts in the United Stated when it opened.

The hotel was located in the present-day Manhattan Beach parking lot, spanning from approximately Jaffray Street to Langham Street. (Recall that all streets east of West End Avenue in Manhattan Beach run in alphabetic order by the first letter of the name, except for Ocean Avenue, which is between Exeter and Falmouth Streets).

The Oriental Hotel had less ocean frontage than the Manhattan Beach Hotel, but several additional floors and spires gave it the appearance of being a significantly more massive structure. The floors were accessible by elevator for the nearly one-thousand guests it could accommodate, and its all-frame building was set on a brick foundation.

Tracy's Tourists' Guide and Companion to Coney Island (1887) describes the building itself in some detail:

'The Oriental Hotel is that large and beautiful structure furthest east, as complete in all its parts as it is possible to build a hotel in this day and age of improvement and invention. It is 6 and 7 stories high, 478 feet long, and ornamented with 8 large circular towers rising 40 feet above the roof, each surmounted by a minaret 15 feet high. There are 480 sleeping rooms, furnished in elegant style, and the character of its guests are of an exclusive class. Quiet and refinement are its prevailing characteristics, and though a most delightful retreat for its guests, the general public find little to draw them to its grounds, save the magnitude and beauty of its surroundings.'

The lobby, halls, and suites were the ultimate in elegance. In the dining room, the superlative cuisine was served table d'hote to the soothing strains from a string quartette. Here were no milling crowds and noisy bands to fray genteel nerves. In the first few seasons, the Oriental was booked to capacity by the families of the rich and filthy rich, while the Manhattan Hotel was relegated to the patronage of the near-rich. Prestigious organizations, as the University Club and the Union League Club, had suites in the Oriental, where their members could relax and recuperate from the arduous daily strain of amassing millions. If guests wished to play croquet, facilities and equipment were available. Tennis, anyone? Six grass courts were conveniently placed east of the hotel. After the Oriental was demolished, in 1916, the courts fell into disuse. When the city took over the Oriental site, the courts were given a clay surface, but poor maintenance made them unusable. In recent years, they were provided with an all-weather surface, and are now in good condition.

As mentioned, the Marine Railroad ran along the entire length of Manhattan Beach. Originally, the rail line was north of the Oriental Hotel, that is, along the present Oriental Boulevard, but a series of storms eroded the north shore of Manhattan Beach, particularly in the Oriental Hotel vicinity, and the waters of Sheepshead Bay began to lap dangerously close to the railroad tracks there. Consequently, the railbed was moved from north of the Oriental Hotel to its south, so that the trains ran between the hotel and the beach. ‘How annoying’, remarked the dowagers, as they observed through their lorgnettes the choo-choo train chugging by on its way to the Point Breeze Hotel, but the children loved it.

Towards the end of September, the entire Manhattan Beach would close down. The hotels were boarded up and the grounds left in the care of Pinkerton detectives until the following season. Most of the 1,100 employees would go south to work in such resort areas as Palm Beach and be back by summer at Manhattan Beach.

On July 4, 1880, Corbin opened his new Oriental Hotel. This palacial resort was approximately two hundred yards east of the Picnic Pavilion, or roughly one thousand yards east of the Manhattan Hotel. The Oriental was Coney Island's flagship hotel and was one of the most technologically sophisticated and refined resorts in the United Stated when it opened.

The hotel was located in the present-day Manhattan Beach parking lot, spanning from approximately Jaffray Street to Langham Street. (Recall that all streets east of West End Avenue in Manhattan Beach run in alphabetic order by the first letter of the name, except for Ocean Avenue, which is between Exeter and Falmouth Streets).

The Oriental Hotel had less ocean frontage than the Manhattan Beach Hotel, but several additional floors and spires gave it the appearance of being a significantly more massive structure. The floors were accessible by elevator for the nearly one-thousand guests it could accommodate, and its all-frame building was set on a brick foundation.

Tracy's Tourists' Guide and Companion to Coney Island (1887) describes the building itself in some detail:

'The Oriental Hotel is that large and beautiful structure furthest east, as complete in all its parts as it is possible to build a hotel in this day and age of improvement and invention. It is 6 and 7 stories high, 478 feet long, and ornamented with 8 large circular towers rising 40 feet above the roof, each surmounted by a minaret 15 feet high. There are 480 sleeping rooms, furnished in elegant style, and the character of its guests are of an exclusive class. Quiet and refinement are its prevailing characteristics, and though a most delightful retreat for its guests, the general public find little to draw them to its grounds, save the magnitude and beauty of its surroundings.'

The lobby, halls, and suites were the ultimate in elegance. In the dining room, the superlative cuisine was served table d'hote to the soothing strains from a string quartette. Here were no milling crowds and noisy bands to fray genteel nerves. In the first few seasons, the Oriental was booked to capacity by the families of the rich and filthy rich, while the Manhattan Hotel was relegated to the patronage of the near-rich. Prestigious organizations, as the University Club and the Union League Club, had suites in the Oriental, where their members could relax and recuperate from the arduous daily strain of amassing millions. If guests wished to play croquet, facilities and equipment were available. Tennis, anyone? Six grass courts were conveniently placed east of the hotel. After the Oriental was demolished, in 1916, the courts fell into disuse. When the city took over the Oriental site, the courts were given a clay surface, but poor maintenance made them unusable. In recent years, they were provided with an all-weather surface, and are now in good condition.

As mentioned, the Marine Railroad ran along the entire length of Manhattan Beach. Originally, the rail line was north of the Oriental Hotel, that is, along the present Oriental Boulevard, but a series of storms eroded the north shore of Manhattan Beach, particularly in the Oriental Hotel vicinity, and the waters of Sheepshead Bay began to lap dangerously close to the railroad tracks there. Consequently, the railbed was moved from north of the Oriental Hotel to its south, so that the trains ran between the hotel and the beach. ‘How annoying’, remarked the dowagers, as they observed through their lorgnettes the choo-choo train chugging by on its way to the Point Breeze Hotel, but the children loved it.

Towards the end of September, the entire Manhattan Beach would close down. The hotels were boarded up and the grounds left in the care of Pinkerton detectives until the following season. Most of the 1,100 employees would go south to work in such resort areas as Palm Beach and be back by summer at Manhattan Beach.

The Coney Island Jockey Club Race Track at Sheepshead Bay (1880)

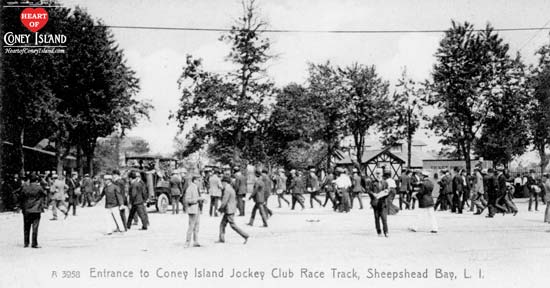

While Corbin was building his Oriental Hotel, the Coney Island Jockey Club, an exclusive social club with a membership roster that read like the Social Register, built a new racetrack at Sheepshead Bay. This Coney Island Jockey Club race track commenced operation on June 19, 1880, about two weeks before the Oriental Hotel opened. It immediately became a huge success, drawing immense crowds on every racing day.

This Sheepshead Bay Race Track became one of the most prestigious in the United States. It included extensive surrounding grounds and was enclosed by a fence that went northward along Ocean Avenue from Jerome Avenue to Neck Road, eastward along Avenue V to about Haring Street, southeastward down Kowenhoven Lane to about Brown Street, then southwest along Voorhies Lane to the intersection of Ocean and Jerome Avenues. An elaborate entrance to the track was at Ocean Avenue. The Manhattan Beach Railroad had a station two hundred yards west of the entrance, and the Brighton Railroad had one 400 yards to the west. The grandstand, facing southeast so as to avoid the glare of the afternoon sun on the ocean, was two stories high and 500 feet long, making it then the largest in the world.

As soon as word went out that the track was to be built, small hotels and restaurants sprouted up in its vicinity. Wealthy people bought land along the shore at the east end of Emmons Avenue and built homes there, with small piers for their yachts. The section became known as Millionaires' Row.

Corbin quickly found a way to make himself one of the chief beneficiaries of the track. He built a road to connect Manhattan Beach to the swells of visitors coming to the Coney Island Jockey Club, and to also make Manhattan Beach accessible to the carriage trade from Ocean Parkway. He laid out a road that ran between the Oriental Boulevard entrance of the Manhattan Hotel and Emmons Avenue to its north, where it turned at a right angle westward into Neptune Avenue, passing under the elevated rails of the Brighton Railroad. The road also crossed the ground-level tracks of Corbin's Manhattan Beach Railroad, where warning gates were erected to prevent accidents. Today, Corbin's road is called West End Avenue.

Corbin also constructed a wooden bridge across a narrow section of Sheepshead Bay for those who wished to walk from the track to Manhattan Beach. At first, Corbin was hesitant about building this footbridge, which might bring undesirable elements from the track. He then decided he could keep the riff raff out by stationing Pinkerton detectives at the Manhattan Beach end of the bridge, many of whom were retired police officers who could spot pickpockets and other disreputable characters.

While Corbin was building his Oriental Hotel, the Coney Island Jockey Club, an exclusive social club with a membership roster that read like the Social Register, built a new racetrack at Sheepshead Bay. This Coney Island Jockey Club race track commenced operation on June 19, 1880, about two weeks before the Oriental Hotel opened. It immediately became a huge success, drawing immense crowds on every racing day.

This Sheepshead Bay Race Track became one of the most prestigious in the United States. It included extensive surrounding grounds and was enclosed by a fence that went northward along Ocean Avenue from Jerome Avenue to Neck Road, eastward along Avenue V to about Haring Street, southeastward down Kowenhoven Lane to about Brown Street, then southwest along Voorhies Lane to the intersection of Ocean and Jerome Avenues. An elaborate entrance to the track was at Ocean Avenue. The Manhattan Beach Railroad had a station two hundred yards west of the entrance, and the Brighton Railroad had one 400 yards to the west. The grandstand, facing southeast so as to avoid the glare of the afternoon sun on the ocean, was two stories high and 500 feet long, making it then the largest in the world.

As soon as word went out that the track was to be built, small hotels and restaurants sprouted up in its vicinity. Wealthy people bought land along the shore at the east end of Emmons Avenue and built homes there, with small piers for their yachts. The section became known as Millionaires' Row.

Corbin quickly found a way to make himself one of the chief beneficiaries of the track. He built a road to connect Manhattan Beach to the swells of visitors coming to the Coney Island Jockey Club, and to also make Manhattan Beach accessible to the carriage trade from Ocean Parkway. He laid out a road that ran between the Oriental Boulevard entrance of the Manhattan Hotel and Emmons Avenue to its north, where it turned at a right angle westward into Neptune Avenue, passing under the elevated rails of the Brighton Railroad. The road also crossed the ground-level tracks of Corbin's Manhattan Beach Railroad, where warning gates were erected to prevent accidents. Today, Corbin's road is called West End Avenue.

Corbin also constructed a wooden bridge across a narrow section of Sheepshead Bay for those who wished to walk from the track to Manhattan Beach. At first, Corbin was hesitant about building this footbridge, which might bring undesirable elements from the track. He then decided he could keep the riff raff out by stationing Pinkerton detectives at the Manhattan Beach end of the bridge, many of whom were retired police officers who could spot pickpockets and other disreputable characters.

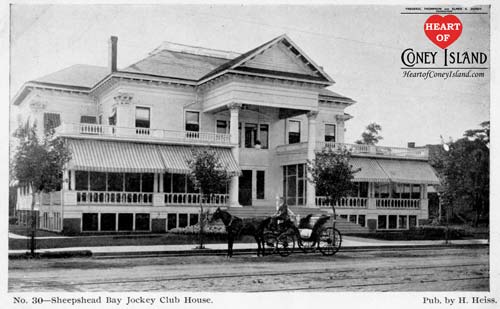

Corbin offered the Coney Island Jockey Club officials a plot of land in Manhattan Beach for their clubhouse. They appeared to be ready to accept, but finally decided to locate it on the north shore of Sheepshead Bay. The last minute switch was induced by one of the governors of the club, August Belmont, Jr. In Germany, his family name had been Schoenberg, which means 'beautiful mountain'. Upon leaving Germany, this Jewish family changed its name to Belmont, which means the same thing in French. While the Belmonts had intermarried with gentiles – one of them marrying the daughter of Admiral Perry – they were offended by Corbin's prior crude assault on their current or former religion, and prevailed on the other governors to reject Corbin's offer. However, it was agreed that a suite be rented in the Oriental Hotel for such members who wished to use its facilities.

Prior to the building of the Sheepshead Bay racetrack, the only restaurant of consequence in the area was the Tappen House, on Emmons Avenue, dating back to 1845. In later years, among the fine dining establishments erected at Sheepshead Bay were Villepigue's Inn, at Ocean and Voorhies Avenues; Lundy's Restaurant, at Ocean and Emmons Avenues; and Beau Rivage and Osborn Hotels on Emmons Avenue. These pleasant restaurants, of course, were not at the same level of lavishness of those found at the Manhattan Beach Hotel and Oriental Hotel across the bay.

Prior to the building of the Sheepshead Bay racetrack, the only restaurant of consequence in the area was the Tappen House, on Emmons Avenue, dating back to 1845. In later years, among the fine dining establishments erected at Sheepshead Bay were Villepigue's Inn, at Ocean and Voorhies Avenues; Lundy's Restaurant, at Ocean and Emmons Avenues; and Beau Rivage and Osborn Hotels on Emmons Avenue. These pleasant restaurants, of course, were not at the same level of lavishness of those found at the Manhattan Beach Hotel and Oriental Hotel across the bay.

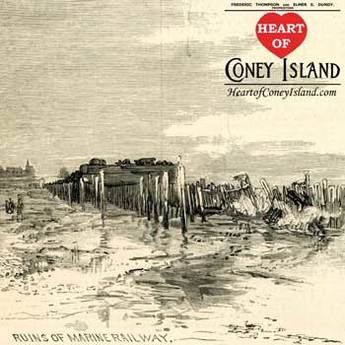

The Marine Beach Railway running between Manhattan Beach and Brighton Beach was always getting demolished. This is from the January 1884 storm (Harper's Weekly, January 19, 1884)

The Marine Beach Railway running between Manhattan Beach and Brighton Beach was always getting demolished. This is from the January 1884 storm (Harper's Weekly, January 19, 1884)

Mother Nature welcomes Manhattan Beach to the 1880s

One of the recurring themes throughout Coney Island history is natural disasters continuously laying ruin to even the most carefully constructed buildings and business plans. Fires, storms, floods and hurricanes were just a part of life.

Storms back then were more devastating to Coney Island than today. First, there were no stone jetties jutting into the ocean to break the force of waves coming in at an angle, which flattened the beach in their outflow. Second, Rockaway Point (also known as Breezy Point), which nowadays protects Coney Island from the ocean’s full force, was then further east. The western end of Rockaway has been accumulating sand and growing southwestward, through some quirk of nature, at the rate of about two hundred feet a year, so that in the past century it has grown some four miles in the direction of Sandy Hook.

A bulwark defense system was erected at both Manhattan Beach and Brighton Beach during the winter of 1880-1881. Corbin backed his piles with boulders for additional support. Bulwarks were the primary means of defending buildings from the full brunt of waves during a storm storms. A typical bulwark might be twenty-five feet deep. The first twenty feet consisted of wooden posts, called piles, implanted vertically deep into the sand in a grid-like pattern. Behind them was a solid wall of wooden planks five feet deep. These bulwarks broke up the force of oncoming waves during storms, lessening their strength and the damage done to buildings further ashore.

In March of 1881, waves from a powerful storm tested these new defenses. The waves leaped over these seawalls and washed away the lawns and auxiliary buildings of the great hotels, but the piles themselves fortunately remained in place. The surf swirled around menacingly under the high stilts under Engeman's Bathing Pavilion. Nearby, it demolished the shuttle railroad that ran along the beach between Manhattan and Brighton Beaches, which had to be hurriedly rebuilt in time for the new season. At West Brighton, which was more protected from storms that Manhattan Beach and especially Brighton Beach, the Iron Pier at West 8th Street, and the New Iron Pier, then under construction, at about West 5th Street, were undamaged.

Mother Nature seemed to have it in for Corbin's shuttle railroad to Brighton. Not much later, in mid-September of 1881, she again washed away its tracks, but left the rest of Coney Island with nothing more than a dunking. Corbin decided to leave the repairs for the following spring, lest further damage be done by winter storms.

One of the recurring themes throughout Coney Island history is natural disasters continuously laying ruin to even the most carefully constructed buildings and business plans. Fires, storms, floods and hurricanes were just a part of life.

Storms back then were more devastating to Coney Island than today. First, there were no stone jetties jutting into the ocean to break the force of waves coming in at an angle, which flattened the beach in their outflow. Second, Rockaway Point (also known as Breezy Point), which nowadays protects Coney Island from the ocean’s full force, was then further east. The western end of Rockaway has been accumulating sand and growing southwestward, through some quirk of nature, at the rate of about two hundred feet a year, so that in the past century it has grown some four miles in the direction of Sandy Hook.

A bulwark defense system was erected at both Manhattan Beach and Brighton Beach during the winter of 1880-1881. Corbin backed his piles with boulders for additional support. Bulwarks were the primary means of defending buildings from the full brunt of waves during a storm storms. A typical bulwark might be twenty-five feet deep. The first twenty feet consisted of wooden posts, called piles, implanted vertically deep into the sand in a grid-like pattern. Behind them was a solid wall of wooden planks five feet deep. These bulwarks broke up the force of oncoming waves during storms, lessening their strength and the damage done to buildings further ashore.

In March of 1881, waves from a powerful storm tested these new defenses. The waves leaped over these seawalls and washed away the lawns and auxiliary buildings of the great hotels, but the piles themselves fortunately remained in place. The surf swirled around menacingly under the high stilts under Engeman's Bathing Pavilion. Nearby, it demolished the shuttle railroad that ran along the beach between Manhattan and Brighton Beaches, which had to be hurriedly rebuilt in time for the new season. At West Brighton, which was more protected from storms that Manhattan Beach and especially Brighton Beach, the Iron Pier at West 8th Street, and the New Iron Pier, then under construction, at about West 5th Street, were undamaged.

Mother Nature seemed to have it in for Corbin's shuttle railroad to Brighton. Not much later, in mid-September of 1881, she again washed away its tracks, but left the rest of Coney Island with nothing more than a dunking. Corbin decided to leave the repairs for the following spring, lest further damage be done by winter storms.

Manhattan Beach put on fun shows that drew large crowds (Leslie's Newspaper, August 6, 1881)

Manhattan Beach put on fun shows that drew large crowds (Leslie's Newspaper, August 6, 1881)

The Manhattan Beach Resort during the mid-1880s

By 1882, it was becoming apparent to Corbin that his two huge hotels in Manhattan Beach were not attracting the upper stratum of society. After a few summer seasons at Manhattan Beach, the wealthiest patrons and their families, who would rent rooms at resorts for weeks at a time during the summer, were drifting back to their old haunts at Saratoga and Newport. Perhaps one reason was that at these more remote resorts, they did not have to endure the occasional entry of untouchables from Ireland, Italy, Spain, Greece, Poland and Germany, among others, who would drift over from West Brighton. Or, perhaps they just wanted a getaway further from home, figuring they could visit Manhattan Beach any time they wanted.

Manhattan Beach nonetheless remained an exclusive and well-visited resort. Theatrical luminaries and prominent politicians, who thrived on the adulation of the crowds, patronized Corbin's establishment. Also, wealthy sportsmen and their entourages, coming to race their horses at Coney Island's tracks, helped to fill his hotels.

For years, Corbin’s most lucrative source of income was Pain's fireworks shows. The bathing pavilion made money, when the weather cooperated. The bars in his hotels were profitable. The Picnic building, which had been the Brazilian Pavilion at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition, made Corbin scowl. Bunches of well-dressed pikers from Brooklyn showed up there with baskets of food brought from home, splurged on a stein of beer, and hung around all day and evening listening to free concerts. In 1883, he moved this building further north, across the tracks of his Marine Railroad, so that his classy clientele in the Oriental Hotel wouldn't have to mingle with those cheapskates.

In being near the city, Manhattan Beach would appear to have had an advantage over Saratoga and Newport, but that was not so where weather was concerned. If it rained, people would rush back to their homes, but at distant Saratoga or Newport, they had to remain in their hotels. Most workers at Manhattan Beach were on a per diem basis. If the sun was out on a Sunday morning, Corbin would put on a full staff of waiters, busboys, and kitchen help; if it rained later that day, the crowd would disappear, and he would be stuck with a full crew which had to be paid for doing nothing. If it rained in the morning, but cleared up in the afternoon, lack of staff would present no problem, for most of the customers coming to Manhattan Beach then would be those nefarious Brooklyn cheapskates, all set to hear a free concert and maybe indulge themselves with a frappe in the ice-cream parlor.