Coney Island History: The Story of Pain's Manhattan Beach Fireworks Shows

Henry J. Pain’s fireworks and pyrotechnics shows were among Coney Island's greatest attractions for over thirty years. Between 1879 and 1910, each of Pain’s elaborate performances drew thousands of spectators to his massive outdoor stadium and lake at Manhattan Beach. The scenes he was able to create using different types of powder and props at night were simply mind-blowing. Pain was a magnificent showman who endowed Coney Island's golden age with much of its glitter.

James Pain’s Shows at London’s Crystal Palace and Alexandra Palace

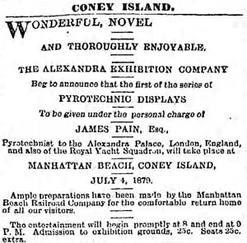

Henry’s father, James Pain, was an English fireworks manufacturer with a flair for show business. James realized that incorporating a storyline into a fireworks show could make it much more interesting than shooting off fireworks alone. James began presenting his unique spectacles in London's Crystal Palace and Alexandra Palace, where they became immensely popular. His shows would use hundreds of actors to reenact historical events or well-known natural disasters involving fires, eruptions or explosions. These plots let James show off his pyrotechnic skills in a logical setting. In the days before film, audience loved seeing reenactments of this type. The shows would culminate in a grand fireworks display.

The Pains arrive at Coney Island (1877)

In 1877, James left his position as the chief pyrotechnist at the Alexandra Palace in London to present his extravaganzas at Manhattan Beach in New York. Henry, then in his late twenties, came with James. James eventually returned to England seven years later, leaving Henry to carry on his work at Coney Island alone.

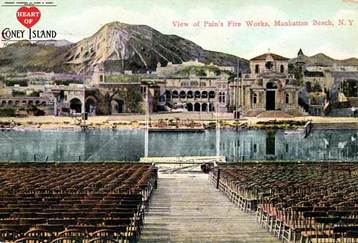

The Pains designed their own stadium, which became known as the Manhattan Beach Amphitheater, on the east side of the bathing and picnic pavilions at Corbin’s Manhattan Beach resort, where it would be safely away from the major wooden structures at the beach. Initially, it had capacity for 10,000 people in total, with 3,000 sitting and 7,000 standing; seating was doubled to 6,000 by the 1886 season, and then doubled again to 12,000 between the 1886 and 1887 seasons. The audience faced a manmade lagoon. An enormous stage, which ran between 500 and 600 feet along the waterfront and went 400 feet back, sat behind the lagoon. The stage had ramps on the three land-facing sides to allow actors to come down to the lake during water scenes.

James Pain’s Shows at London’s Crystal Palace and Alexandra Palace

Henry’s father, James Pain, was an English fireworks manufacturer with a flair for show business. James realized that incorporating a storyline into a fireworks show could make it much more interesting than shooting off fireworks alone. James began presenting his unique spectacles in London's Crystal Palace and Alexandra Palace, where they became immensely popular. His shows would use hundreds of actors to reenact historical events or well-known natural disasters involving fires, eruptions or explosions. These plots let James show off his pyrotechnic skills in a logical setting. In the days before film, audience loved seeing reenactments of this type. The shows would culminate in a grand fireworks display.

The Pains arrive at Coney Island (1877)

In 1877, James left his position as the chief pyrotechnist at the Alexandra Palace in London to present his extravaganzas at Manhattan Beach in New York. Henry, then in his late twenties, came with James. James eventually returned to England seven years later, leaving Henry to carry on his work at Coney Island alone.

The Pains designed their own stadium, which became known as the Manhattan Beach Amphitheater, on the east side of the bathing and picnic pavilions at Corbin’s Manhattan Beach resort, where it would be safely away from the major wooden structures at the beach. Initially, it had capacity for 10,000 people in total, with 3,000 sitting and 7,000 standing; seating was doubled to 6,000 by the 1886 season, and then doubled again to 12,000 between the 1886 and 1887 seasons. The audience faced a manmade lagoon. An enormous stage, which ran between 500 and 600 feet along the waterfront and went 400 feet back, sat behind the lagoon. The stage had ramps on the three land-facing sides to allow actors to come down to the lake during water scenes.

Pain's Inaugural Show (1879)

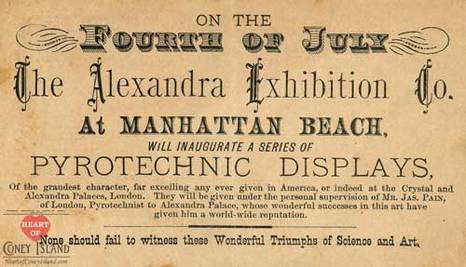

The Pains, under the banner of their Alexandra Exhibition Company, scheduled their first show for the evening of July Fourth of 1879 at Manhattan Beach. As of late June, they were still rushing to finish up the stadium and props. Everything at Coney Island tended to get done just in the nick of time, and these famed Englishmen were no exception.

The inaugural show was designed to be absolutely stunning. It included approximately twenty individual pyrotechnic displays, each transitioning from one to the other in serial order. There were traditional fireworks like we see today on holidays, of course. But Pain went much, much further. He created elaborate scenes using props and meticulously prepared burning powders, in what essentially amounted to a display of nighttime art that you might expect would be possible only using multicolored LED lights. His Mammoth Silver Fire Wheel measured 51 feet in diameter and had concentric circles that would all change color, with certain colors appearing to travel from the inside to the outside and back, like the lights on a modern Ferris wheel. The 40-foot-tall Fairy Fountain had gold and silver jets streaming out of it. Perhaps the most amazing display was the recreation of what appeared to be an entire riverboat moving as it paddled its way along a river.

Over 100,000 people came to Coney Island that July Fourth, many expecting to see Pain’s show or perhaps take a ride in Professor King’s novel hot air balloon ride, also being inaugurated at Manhattan Beach. But the crowds would have to wait. A strong summer storm appeared that evening, preventing the Pains from putting on their show and the professor from giving rides to any of the 2,000 people who were eagerly waiting. The heavy rains even damaged some of the Pains’ props.

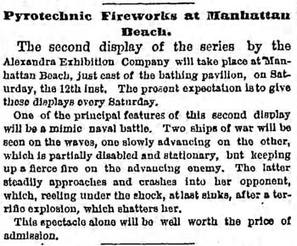

Undeterred, the Pains went ahead with their second show on Saturday, July 12th, and augmented it with a naval battle that really amazed audiences. In it, as a damaged warship tried to fight off its opponent, streams of lights arced out of each ship as they fired on each other. The scene culminated with the damaged ship being rammed by the attacker and sinking. For the rest of the 1879 season and the next several seasons, the Pains performed this show every Saturday evening. Some of the props changed from season to season, but the overall show remained largely consistent.

Over this time, the Pains also put on a show called ‘The Battle of the Monitor and the Merrimac’, which recreated the famous Civil War naval battle between these two ironclad ships. The Pains created realistic replicas of the ships that were slightly scaled-down versions of the real vessels, and closed the performance with their signature world-class fireworks and pyrotechnics display above the stage. The show would be brought back from time to time in future years, including 1887.

The Pains, under the banner of their Alexandra Exhibition Company, scheduled their first show for the evening of July Fourth of 1879 at Manhattan Beach. As of late June, they were still rushing to finish up the stadium and props. Everything at Coney Island tended to get done just in the nick of time, and these famed Englishmen were no exception.

The inaugural show was designed to be absolutely stunning. It included approximately twenty individual pyrotechnic displays, each transitioning from one to the other in serial order. There were traditional fireworks like we see today on holidays, of course. But Pain went much, much further. He created elaborate scenes using props and meticulously prepared burning powders, in what essentially amounted to a display of nighttime art that you might expect would be possible only using multicolored LED lights. His Mammoth Silver Fire Wheel measured 51 feet in diameter and had concentric circles that would all change color, with certain colors appearing to travel from the inside to the outside and back, like the lights on a modern Ferris wheel. The 40-foot-tall Fairy Fountain had gold and silver jets streaming out of it. Perhaps the most amazing display was the recreation of what appeared to be an entire riverboat moving as it paddled its way along a river.

Over 100,000 people came to Coney Island that July Fourth, many expecting to see Pain’s show or perhaps take a ride in Professor King’s novel hot air balloon ride, also being inaugurated at Manhattan Beach. But the crowds would have to wait. A strong summer storm appeared that evening, preventing the Pains from putting on their show and the professor from giving rides to any of the 2,000 people who were eagerly waiting. The heavy rains even damaged some of the Pains’ props.

Undeterred, the Pains went ahead with their second show on Saturday, July 12th, and augmented it with a naval battle that really amazed audiences. In it, as a damaged warship tried to fight off its opponent, streams of lights arced out of each ship as they fired on each other. The scene culminated with the damaged ship being rammed by the attacker and sinking. For the rest of the 1879 season and the next several seasons, the Pains performed this show every Saturday evening. Some of the props changed from season to season, but the overall show remained largely consistent.

Over this time, the Pains also put on a show called ‘The Battle of the Monitor and the Merrimac’, which recreated the famous Civil War naval battle between these two ironclad ships. The Pains created realistic replicas of the ships that were slightly scaled-down versions of the real vessels, and closed the performance with their signature world-class fireworks and pyrotechnics display above the stage. The show would be brought back from time to time in future years, including 1887.

Last Days of Pompeii (1882)

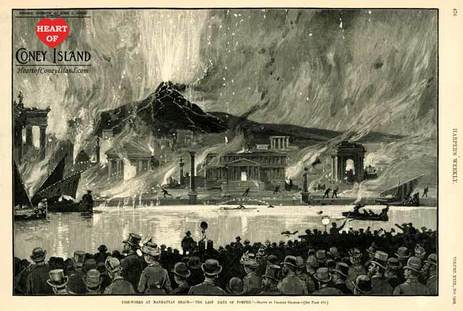

Ahead of the 1882 season, the Pains had the novel idea of combining their fireworks displays into a broader show with a plot and music. Their first creation in this new genre was The Last Days of Pompeii, and it proved to be a spectacular hit that quickly became the talk of the entertainment world. As the Pains’ fame spread in the United States, they were invited to present their creations at state fairs and international expositions during Coney Island's off-season. The show was so successful that they would end up featuring it during several future seasons as well.

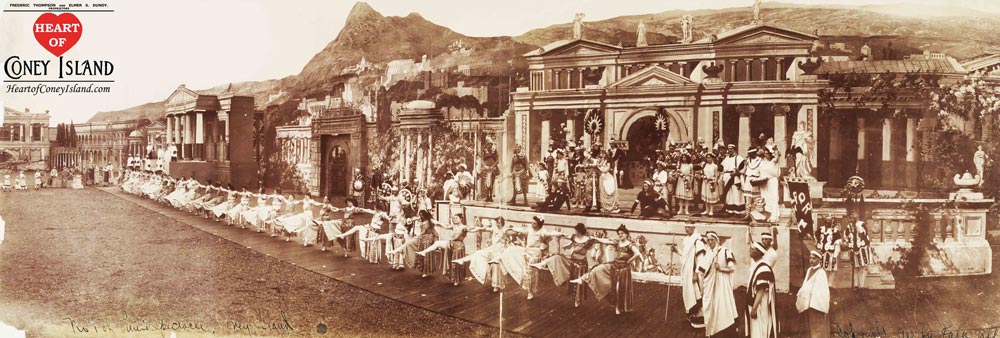

The Last Days of Pompeii featured the ancient city of Pompeii being destroyed by the eruption of Vesuvius, a nearby volcano. The audience would buy tickets and then enter the Pains’ stadium, sitting down in one of the tiered seats. Manhattan Beach’s resident band, led at this time by the exceptionally popular conductor Gilmore, sat below the audience at the lake’s shore. Across the lake, the stage lay in darkness at this point, while the audience’s side was illuminated by electric lights, a novelty first exhibited at the Philadelphia Centennial Celebration in 1876. Once everyone was seated and the show was about to start, the lights in the stadium were turned off, and the lights across the lagoon were turned on, revealing a plaza on the Bay of Naples shore of the ancient Italian city of Pompeii, with the volcano, Vesuvius, in the background. Large, accurate reproductions of Temple of Isis, the city’s amphitheater and other buildings gave the set very realistic feel. In the plaza, children played, skipping rope, rolling hoops, shooting marbles, or watching the little monkey of the hurdy-gurdy man. People in colorful native costumes gradually gathered in the plaza, a religious procession went by, and then a festival began, with group singing and dancing. Clowns appear, along with jugglers and acrobats. While the citizens were enjoying themselves, they are unaware of what the audience saw, namely smoke, starting as a wisp, then increasing in density, arising from the volcano. Suddenly there was a rumble, a plume of fire arose amidst the smoke, and all on the stage became momentarily silent. Some people rushed to a corner, where they could see the volcano. A louder rumble than before was heard, with terror and panic breaking out among the people in the plaza. The volcano spewed fire and ash upon the city, and fires broke out everywhere, and lava appeared to flow down the mountain, engulfing Pompeii in a general conflagration. Some townspeople managed to escape by boat, including the children first seen playing in the plaza. This is done so that the audience would not be upset by seeing children perish. Finally, the Pains let loose with a brilliant fireworks display. These shows usually lasted about an hour, but later, as Corbin added more attractions elsewhere, he asked the Pains to shorten the time to about a half an hour.

Ahead of the 1882 season, the Pains had the novel idea of combining their fireworks displays into a broader show with a plot and music. Their first creation in this new genre was The Last Days of Pompeii, and it proved to be a spectacular hit that quickly became the talk of the entertainment world. As the Pains’ fame spread in the United States, they were invited to present their creations at state fairs and international expositions during Coney Island's off-season. The show was so successful that they would end up featuring it during several future seasons as well.

The Last Days of Pompeii featured the ancient city of Pompeii being destroyed by the eruption of Vesuvius, a nearby volcano. The audience would buy tickets and then enter the Pains’ stadium, sitting down in one of the tiered seats. Manhattan Beach’s resident band, led at this time by the exceptionally popular conductor Gilmore, sat below the audience at the lake’s shore. Across the lake, the stage lay in darkness at this point, while the audience’s side was illuminated by electric lights, a novelty first exhibited at the Philadelphia Centennial Celebration in 1876. Once everyone was seated and the show was about to start, the lights in the stadium were turned off, and the lights across the lagoon were turned on, revealing a plaza on the Bay of Naples shore of the ancient Italian city of Pompeii, with the volcano, Vesuvius, in the background. Large, accurate reproductions of Temple of Isis, the city’s amphitheater and other buildings gave the set very realistic feel. In the plaza, children played, skipping rope, rolling hoops, shooting marbles, or watching the little monkey of the hurdy-gurdy man. People in colorful native costumes gradually gathered in the plaza, a religious procession went by, and then a festival began, with group singing and dancing. Clowns appear, along with jugglers and acrobats. While the citizens were enjoying themselves, they are unaware of what the audience saw, namely smoke, starting as a wisp, then increasing in density, arising from the volcano. Suddenly there was a rumble, a plume of fire arose amidst the smoke, and all on the stage became momentarily silent. Some people rushed to a corner, where they could see the volcano. A louder rumble than before was heard, with terror and panic breaking out among the people in the plaza. The volcano spewed fire and ash upon the city, and fires broke out everywhere, and lava appeared to flow down the mountain, engulfing Pompeii in a general conflagration. Some townspeople managed to escape by boat, including the children first seen playing in the plaza. This is done so that the audience would not be upset by seeing children perish. Finally, the Pains let loose with a brilliant fireworks display. These shows usually lasted about an hour, but later, as Corbin added more attractions elsewhere, he asked the Pains to shorten the time to about a half an hour.

Bombardment of Alexandria (1883)

In 1883, Pain's contribution to the festivities at Manhattan Beach that summer was the Bombardment of Alexandria, an event that had made the headlines the year before during the British conquest of Egypt to protect their interests in the Suez Canal.

Storming of Pekin (1884)

Pain's contribution to the entertainment at Manhattan Beach in 1884 was a spectacle called The Storming of Pekin, which had to do with an event of the Japanese-Chinese war then in progress.

Last Days of Pompeii (1885)

Pain's fire show in the 1885 season at Manhattan Beach was another revival of his Last Days of Pompeii.

In 1883, Pain's contribution to the festivities at Manhattan Beach that summer was the Bombardment of Alexandria, an event that had made the headlines the year before during the British conquest of Egypt to protect their interests in the Suez Canal.

Storming of Pekin (1884)

Pain's contribution to the entertainment at Manhattan Beach in 1884 was a spectacle called The Storming of Pekin, which had to do with an event of the Japanese-Chinese war then in progress.

Last Days of Pompeii (1885)

Pain's fire show in the 1885 season at Manhattan Beach was another revival of his Last Days of Pompeii.

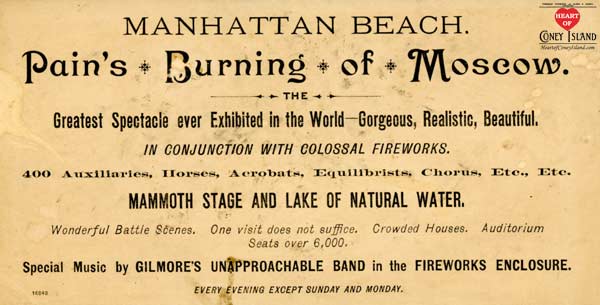

Burning of Moscow (1886)

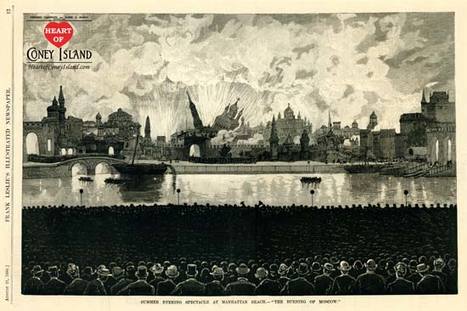

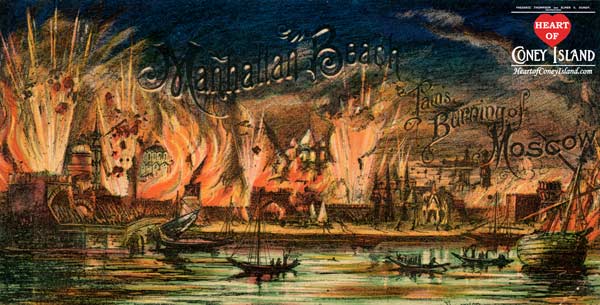

Pain’s 1886 show, the Burning of Moscow, was a blowout that had customers standing in the aisles. He had elaborate sets built on his stage to represent the city of Moscow, with a plaza at the water's edge, where a Russian festival would take place. Though Gilmore's band provided most of the music, there were Russian musicians on stage strumming their balalaikas to lend authenticity to the scene. Peasants, in native costumes, were grouped in the square, some dancing while others clapped their hands in time with the music. A religious procession went by intoning sacred hymns. Russian infantry marched in, engaged in military drills, and then departed in formation into the city. There was further dancing and singing, which came to a halt at the sound of distant cannon fire. The civilians scattered in alarm to their homes. There was an increasing tumult of cannon and infantry fire, along with the sound of drums and bugles. Russian troops emerged from the city in retreat and disappeared off-stage. French troops came into view, pursuing Russian stragglers, whom they engaged in sword and bayonet fights. Presently, the plaza became filled with French troops, who arrayed in formation as Napoleon rode in on a white charger to the acclamation of his men. As the Marseillaise was played, fires broke out throughout the city, and, in a greatly compressed time frame, the French began their retreat from Moscow. Russian troops reappeared, firing after the French and following the withdrawing enemy into the burning city. A column of Cossacks, with flashing sabers, galloped onto the stage and followed the infantry in pursuit of the French. With all of Moscow aflame, Pain cut loose with a sky full of bursting rockets. During the fighting, Pain was inclined to simulate artillery shells exploding in the lagoon, in order to add a touch of realism to the scene, but was dissuaded by the possibility that the audience might flee in panic.

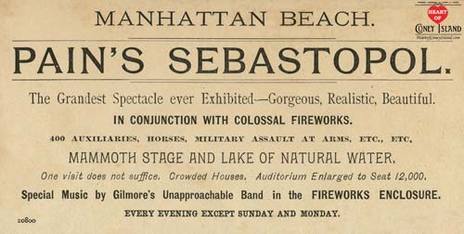

Siege of Sebastopol (1887)

No sooner had Pain finished putting Napoleon's army to flight every night in the week, except Sunday, for the summer season of 1886, than he began planning his next spectacular for the 1887 season. It had to do with Sebastopol, in the Crimean War, which had England, France and Turkey fighting Russia. Why? Few knew the reason for the war, which arose from a dispute between Greek Catholic and Roman Catholic monks, and which is as good a reason to start a war as any. And why would Americans be interested in anything that happened in the Crimean War? It all had to do with a poem by Alfred Lord Tennyson called The Charge of the Light Brigade, which every American and British schoolboy recited, and often memorized. Pain knew, along with the Chinese, that one picture is worth a thousand words, so he planned to reenact the charge of the English Light Horse against the Russian artillery at Balaclava. This would be the climax, preceded by the usual dancing and singing by English and Russian soldiers. A highlight of the entertainment would be a sentimental song of home delivered by a pretty girl acting the part of the nurse, Florence Nightingale. Battle scenes in unpopulated areas appealed to Corbin because they required no sets to speak of. The horses used in cavalry charges were rented from the army, because only animals trained not to take fright in the face of cannon fire could be employed for such purposes.

Separately, another record states that Pain also put on a show called ‘The Battle of the Monitor and the Merrimac’ at other times during the 1887 season, such as on September 17th.

Pain’s 1886 show, the Burning of Moscow, was a blowout that had customers standing in the aisles. He had elaborate sets built on his stage to represent the city of Moscow, with a plaza at the water's edge, where a Russian festival would take place. Though Gilmore's band provided most of the music, there were Russian musicians on stage strumming their balalaikas to lend authenticity to the scene. Peasants, in native costumes, were grouped in the square, some dancing while others clapped their hands in time with the music. A religious procession went by intoning sacred hymns. Russian infantry marched in, engaged in military drills, and then departed in formation into the city. There was further dancing and singing, which came to a halt at the sound of distant cannon fire. The civilians scattered in alarm to their homes. There was an increasing tumult of cannon and infantry fire, along with the sound of drums and bugles. Russian troops emerged from the city in retreat and disappeared off-stage. French troops came into view, pursuing Russian stragglers, whom they engaged in sword and bayonet fights. Presently, the plaza became filled with French troops, who arrayed in formation as Napoleon rode in on a white charger to the acclamation of his men. As the Marseillaise was played, fires broke out throughout the city, and, in a greatly compressed time frame, the French began their retreat from Moscow. Russian troops reappeared, firing after the French and following the withdrawing enemy into the burning city. A column of Cossacks, with flashing sabers, galloped onto the stage and followed the infantry in pursuit of the French. With all of Moscow aflame, Pain cut loose with a sky full of bursting rockets. During the fighting, Pain was inclined to simulate artillery shells exploding in the lagoon, in order to add a touch of realism to the scene, but was dissuaded by the possibility that the audience might flee in panic.

Siege of Sebastopol (1887)

No sooner had Pain finished putting Napoleon's army to flight every night in the week, except Sunday, for the summer season of 1886, than he began planning his next spectacular for the 1887 season. It had to do with Sebastopol, in the Crimean War, which had England, France and Turkey fighting Russia. Why? Few knew the reason for the war, which arose from a dispute between Greek Catholic and Roman Catholic monks, and which is as good a reason to start a war as any. And why would Americans be interested in anything that happened in the Crimean War? It all had to do with a poem by Alfred Lord Tennyson called The Charge of the Light Brigade, which every American and British schoolboy recited, and often memorized. Pain knew, along with the Chinese, that one picture is worth a thousand words, so he planned to reenact the charge of the English Light Horse against the Russian artillery at Balaclava. This would be the climax, preceded by the usual dancing and singing by English and Russian soldiers. A highlight of the entertainment would be a sentimental song of home delivered by a pretty girl acting the part of the nurse, Florence Nightingale. Battle scenes in unpopulated areas appealed to Corbin because they required no sets to speak of. The horses used in cavalry charges were rented from the army, because only animals trained not to take fright in the face of cannon fire could be employed for such purposes.

Separately, another record states that Pain also put on a show called ‘The Battle of the Monitor and the Merrimac’ at other times during the 1887 season, such as on September 17th.

Great Fire of London (1888)

Pain's offering in 1888 was The Great Fire of London, which had taken place in 1666. No doubt, many spectators, who disliked the English because they were Irish or Scotch, or because of the American Revolution and War of 1812, or because the English had sided with the Confederates in the Civil War, got some satisfaction in seeing London go up in flames. Pain tried to please everyone, even if it meant having to hear applause as he burned down his own native city.

Last Days of Pompeii (1889)

At Manhattan Beach, in 1889, Pain brought back his greatest hit, The Last Days of Pompeii. By this time, Pain’s shows were absolutely massive performances; this show featured five-hundred actors, one-hundred dancers from the Metropolitan Ballet company, fifty members of the Metropolitan Chorus, and numerous acrobats.

Siege of Vera Cruz (1890)

This fireshow was notable because not only did Pain's cannon set Vera Cruz afire, but his rockets came close to doing the same to Corbin’s prized Oriental Hotel, when several landed on the roof and began smoldering. The fires were extinguished before they could do much damage, but must have given Corbin indigestion in the process.

Pain's offering in 1888 was The Great Fire of London, which had taken place in 1666. No doubt, many spectators, who disliked the English because they were Irish or Scotch, or because of the American Revolution and War of 1812, or because the English had sided with the Confederates in the Civil War, got some satisfaction in seeing London go up in flames. Pain tried to please everyone, even if it meant having to hear applause as he burned down his own native city.

Last Days of Pompeii (1889)

At Manhattan Beach, in 1889, Pain brought back his greatest hit, The Last Days of Pompeii. By this time, Pain’s shows were absolutely massive performances; this show featured five-hundred actors, one-hundred dancers from the Metropolitan Ballet company, fifty members of the Metropolitan Chorus, and numerous acrobats.

Siege of Vera Cruz (1890)

This fireshow was notable because not only did Pain's cannon set Vera Cruz afire, but his rockets came close to doing the same to Corbin’s prized Oriental Hotel, when several landed on the roof and began smoldering. The fires were extinguished before they could do much damage, but must have given Corbin indigestion in the process.

Paris, from Empire to Commune (1891)

Pain's fireshow of Paris, From Empire to Commune, dealt with the Franco-Prussian War, the siege of Paris, and the end of the reign of Napoleon III.

Carnival of Venice, at West Brighton (1892)

At the end of the 1891 season in Coney Island, the Sea Beach Company executives were contemplating the creation of an amusement park in a large, barren section of their property at West Brighton. Specifically, the land was where Luna Park would be built twelve years later, just to the immediate northwest of the company's Sea Beach Palace, and just north of the Elephant Hotel. To draw attention to the area, it was agreed that a spectacular show should be presented there, and that the man best qualified to put it on was Henry J. Pain. The mere mention that Pain's show would be at competing West Brighton for the 1892 season, instead of Manhattan Beach, would draw immense crowds.

Pain had a season-to-season contract with Corbin that either could terminate. When Pain informed Corbin of the lucrative offer he had received from the Sea Beach Company, Corbin refused to match it, believing that Pain would not make the switch. Pain nonetheless signed a contract with the Sea Beach Company for the 1892 season. Corbin had to get a pyrotechnician named Brock for that season. Brock put on elaborate fireworks displays, but he was no showman like Pain. Corbin learned his lesson.

With the opening of the 1892 season on Decoration Day, the big event in Coney Island was Pain’s new extravaganza at West Brighton, called The Carnival of Venice. The centerpiece of Pain's presentation was a replica of the Plaza San Marco in Venice, complete with canals and bridges. Audiences seated in stands across the lagoon watched hundreds of performers in native dress dancing and cavorting in the plaza. Gondolas would course along the canals, and troubadours would move through the crowds singing and playing mandolins. There would be affronts to ladies, some wearing black laced masks, leading their escorts to engage in sword-play with the offenders. One young lady quarreled with her sweetheart after catching him flirting with another; in a jealous rage, she plunged a dagger into his chest, only to fall weeping on his body. These were the typical vignettes that Pain would add to make his crowd scenes more interesting. Unlike his shows at Manhattan Beach, this one ended neither in a manmade nor natural disaster. The finale had a grand chorus at center stage, with dancers on the wings, followed by fireworks. After the performance, those in the audience who wished to take a gondola ride, with musical accompaniment, could do so for an extra charge.

The Tilyous were so impressed by Pain's Carnival of Venice that when they built their Steeplechase Park five years later, they had similar canals created on their grounds, as well as the bridges over them. Some of the bridges were covered and called ‘kissing bridges’, for the obvious purpose of attracting romantic couples.

Siege and Storming of Vicksburg (1893)

For 1893, Pain was back at the Manhattan Beach pyrotechnical stadium with The Siege and Storming of Vicksburg. This elaborate reenactment employed five-hundred infantry, two cavalry squadrons and two artillery batteries. Pain also had some gunboats in the lagoon, which represented the Mississippi River, to join in the bombardment and capture of Vicksburg. Before hostilities commenced, Pain two-hundred ‘jubilee singers’ entertained the audience with a scene of plantation life. If Corbin was paying the bill for all this, he was having his nose rubbed in the sand by Pain for having failed to match the Sea Beach Company's bid in the previous year.

Lalla Rookh (1894)

Pain's offering that season was a lavish oriental display called Lalla Rookh, based on a lengthy poem of that name by the Irish bard, Thomas Moore. It was a Romeo and Juliet type of love story between a prince of Persian fire-worshippers and an Arabian princess. In the end, after a conflict between the fire-worshippers and the Arabians, the prince dies in a volcanic eruption, whereupon the princess leaps to her death into a lake.

Capture of Port Arthur (1895)

Pain, in 1895, presented The Capture of Port Arthur, an event of the Chinese-Japanese War then taking place. An elaborate ballet showing Chinese and Japanese people in their native costumes preceded the hostilities.

Cuba (1896)

During 1886, there was an uprising by Cubans against their Spanish overlords. Most Americans generally sympathized with the Cuban cause, leading Pain to offer ‘Cuba’, which adapted some of the characters from Bizet's opera, Carmen. Carmen becomes a Cuban patriot inducing the Spanish officer, Escamillo, to desert to the rebels. In one scene, Pain has several Cubans being executed by a Spanish firing squad, despite the demands by an American ambassador that they be released because they are American citizens.

Separately, Corbin died in June of 1896 from injuries in a horse carriage accident. His death did not impact Pain’s performances or general Manhattan Beach operations.

Greece and Turkey (1897)

During 1897, Pain presented another topical subject at Manhattan Beach, Greece and Turkey. These nations had gotten into a war over a dispute regarding the island of Crete, and the great powers had intervened to end the hostilities. As usual, Pain had musicians, singers and dancers of the two nations performing before the battle scene and the fireworks.

Battle of San Juan Hill (1898, 1899)

In February of 1898, the United States battleship ‘Maine’ was sunk in Havana harbor, leading the United States into a war with Spain. On May 1, 1898, Admiral George Dewey’s Pacific Fleet sunk part of the Spanish fleet at Manila Bay in the Philippines. Pain hastened to assemble replicas of both fleets, in miniature, in time to present the battle at the opening of the 1898 season at Manhattan Beach. Teddy Roosevelt himself saw and approved of Pain's Battle of San Juan Hill in 1899.

Fujiyama (1900)

Pain's show for the 1900 season was Fujiyama, the snow-capped volcano in Japan. An elaborate Japanese festival scene preceded the inevitable volcanic eruption. Pain's costume and scenic designer, Kirby, said that it was the most sumptuous production he had ever created.

Pain's fireshow of Paris, From Empire to Commune, dealt with the Franco-Prussian War, the siege of Paris, and the end of the reign of Napoleon III.

Carnival of Venice, at West Brighton (1892)

At the end of the 1891 season in Coney Island, the Sea Beach Company executives were contemplating the creation of an amusement park in a large, barren section of their property at West Brighton. Specifically, the land was where Luna Park would be built twelve years later, just to the immediate northwest of the company's Sea Beach Palace, and just north of the Elephant Hotel. To draw attention to the area, it was agreed that a spectacular show should be presented there, and that the man best qualified to put it on was Henry J. Pain. The mere mention that Pain's show would be at competing West Brighton for the 1892 season, instead of Manhattan Beach, would draw immense crowds.

Pain had a season-to-season contract with Corbin that either could terminate. When Pain informed Corbin of the lucrative offer he had received from the Sea Beach Company, Corbin refused to match it, believing that Pain would not make the switch. Pain nonetheless signed a contract with the Sea Beach Company for the 1892 season. Corbin had to get a pyrotechnician named Brock for that season. Brock put on elaborate fireworks displays, but he was no showman like Pain. Corbin learned his lesson.

With the opening of the 1892 season on Decoration Day, the big event in Coney Island was Pain’s new extravaganza at West Brighton, called The Carnival of Venice. The centerpiece of Pain's presentation was a replica of the Plaza San Marco in Venice, complete with canals and bridges. Audiences seated in stands across the lagoon watched hundreds of performers in native dress dancing and cavorting in the plaza. Gondolas would course along the canals, and troubadours would move through the crowds singing and playing mandolins. There would be affronts to ladies, some wearing black laced masks, leading their escorts to engage in sword-play with the offenders. One young lady quarreled with her sweetheart after catching him flirting with another; in a jealous rage, she plunged a dagger into his chest, only to fall weeping on his body. These were the typical vignettes that Pain would add to make his crowd scenes more interesting. Unlike his shows at Manhattan Beach, this one ended neither in a manmade nor natural disaster. The finale had a grand chorus at center stage, with dancers on the wings, followed by fireworks. After the performance, those in the audience who wished to take a gondola ride, with musical accompaniment, could do so for an extra charge.

The Tilyous were so impressed by Pain's Carnival of Venice that when they built their Steeplechase Park five years later, they had similar canals created on their grounds, as well as the bridges over them. Some of the bridges were covered and called ‘kissing bridges’, for the obvious purpose of attracting romantic couples.

Siege and Storming of Vicksburg (1893)

For 1893, Pain was back at the Manhattan Beach pyrotechnical stadium with The Siege and Storming of Vicksburg. This elaborate reenactment employed five-hundred infantry, two cavalry squadrons and two artillery batteries. Pain also had some gunboats in the lagoon, which represented the Mississippi River, to join in the bombardment and capture of Vicksburg. Before hostilities commenced, Pain two-hundred ‘jubilee singers’ entertained the audience with a scene of plantation life. If Corbin was paying the bill for all this, he was having his nose rubbed in the sand by Pain for having failed to match the Sea Beach Company's bid in the previous year.

Lalla Rookh (1894)

Pain's offering that season was a lavish oriental display called Lalla Rookh, based on a lengthy poem of that name by the Irish bard, Thomas Moore. It was a Romeo and Juliet type of love story between a prince of Persian fire-worshippers and an Arabian princess. In the end, after a conflict between the fire-worshippers and the Arabians, the prince dies in a volcanic eruption, whereupon the princess leaps to her death into a lake.

Capture of Port Arthur (1895)

Pain, in 1895, presented The Capture of Port Arthur, an event of the Chinese-Japanese War then taking place. An elaborate ballet showing Chinese and Japanese people in their native costumes preceded the hostilities.

Cuba (1896)

During 1886, there was an uprising by Cubans against their Spanish overlords. Most Americans generally sympathized with the Cuban cause, leading Pain to offer ‘Cuba’, which adapted some of the characters from Bizet's opera, Carmen. Carmen becomes a Cuban patriot inducing the Spanish officer, Escamillo, to desert to the rebels. In one scene, Pain has several Cubans being executed by a Spanish firing squad, despite the demands by an American ambassador that they be released because they are American citizens.

Separately, Corbin died in June of 1896 from injuries in a horse carriage accident. His death did not impact Pain’s performances or general Manhattan Beach operations.

Greece and Turkey (1897)

During 1897, Pain presented another topical subject at Manhattan Beach, Greece and Turkey. These nations had gotten into a war over a dispute regarding the island of Crete, and the great powers had intervened to end the hostilities. As usual, Pain had musicians, singers and dancers of the two nations performing before the battle scene and the fireworks.

Battle of San Juan Hill (1898, 1899)

In February of 1898, the United States battleship ‘Maine’ was sunk in Havana harbor, leading the United States into a war with Spain. On May 1, 1898, Admiral George Dewey’s Pacific Fleet sunk part of the Spanish fleet at Manila Bay in the Philippines. Pain hastened to assemble replicas of both fleets, in miniature, in time to present the battle at the opening of the 1898 season at Manhattan Beach. Teddy Roosevelt himself saw and approved of Pain's Battle of San Juan Hill in 1899.

Fujiyama (1900)

Pain's show for the 1900 season was Fujiyama, the snow-capped volcano in Japan. An elaborate Japanese festival scene preceded the inevitable volcanic eruption. Pain's costume and scenic designer, Kirby, said that it was the most sumptuous production he had ever created.

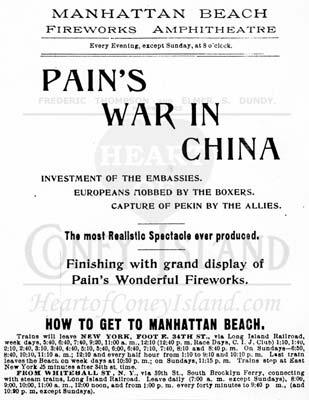

War in China, ak.a. Boxer Rebellion (1901)

The subject of Pain's show in 1901 was the Boxer Rebellion in China.

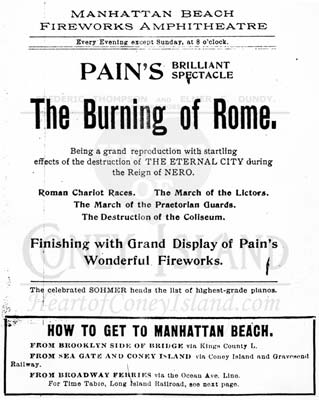

Burning of Rome (1902)

Early in 1902, after giving some thought as to his next presentation at Manhattan Beach, Pain decided to burn down Rome; not modern Rome, but that of the Emperor Nero.

As we know, Nero was an effete aesthete, blue-eyed and blond, and adept at acting, singing, dancing, poetical and musical composition, lyre-playing, and murder. As the story goes, one day, while standing on the balcony of his palace overlooking Rome, Nero asked himself the rhetorical question, ‘What am I emperor of?’ To which he answered, ‘I am emperor of the world.’ Yet, the capital of his empire was in his eyes an ugly, unsightly mess, an abomination called Rome. Nero decided that an emperor as noble and beautiful as himself should have a magnificent metropolis worthy of such a sublime being. Then and there, Nero decided to build a new city, and the quickest way of starting that urban-renewal project was to burn down the existing pile of rubbish.

Pain assigned his scenic artist, Kirby, to building a replica of ancient Rome. Nero's palace was placed at one side of a plaza on the shore of the lagoon, which represented the Tiber River. Hundreds of extras were fitted out in the uniforms of Roman legionnaires and praetorian guards, and taught to march to the cadence of beating cymbals and blaring trumpets. Hundreds of others were outfitted with togas and sandals to represent the populace of Rome. Robust types were chosen as gladiators, and instructed in how to duel with swords, spears, tridents, and nets.

At the first performance, ten thousand spectators filled the seats facing the Tibor and the City of Rome. They witnessed chariot races, marching troops, gladiatorial combats, and a colorful pageant. After the crowds had departed from the square, Nero, who had been watching the festivities from his balcony, pointed to the city, and out of the floor below men with flaming torches emerged, and rushed into Rome to set it afire. As the flames appeared in many quarters, Nero smiled, clapped his hands in delight, and did a little dance with arms aloft. Then, as the fires merged into one great conflagration, he picked up a violin and did a Paganini. Of course, there were no violins in Nero's time, so he must have plucked the strings of his lyre, but Pain was not one to fiddle with tradition. The show ended in a blaze of glory, with thousands of rockets lighting up the night sky. Had Nero witnessed the spectacle, he would have heaped honors on Pain; and then, for Pain's attempt to excel him in conflagrations, he certainly would have treated him to a hemlock cocktail.

Last Days of Pompeii (1903)

Before the 1903 season began, the Manhattan Beach management suggested to Pain that it might be economical to repeat some of his earlier shows. The scenery and sets of former shows were stored in warehouses and going to waste. Pain agreed, bringing back his first love, The Last Days of Pompeii, for the 1903 season. It broke all prior attendance records, with the Tammany Times reporting that 12,780 people attended on July Fourth, with another 8,000 being turned away at the gates for lack of room. The show ran nightly at 8 p.m.

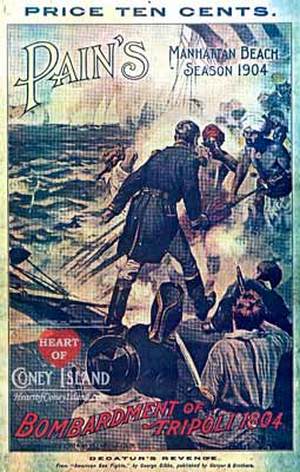

Bombardment of Tripoli, a.k.a. Decatur’s Revenge (1904)

In planning his program for 1904, Pain became aware that it would be the 100th anniversary of the raid by Captain Stephen Decatur's marines on the port of Tripoli in Algeria (now in Libya). Decatur succeeded in burning the American frigate ‘Philadelphia’, which had been captured by the Barbary pirates.

Playing fast and loose with history, Pain had this event ending the war. During the show, the Bashaw, who was the ruler of Tripoli, entered the plaza in front of the city, on the shore of the Mediterranean Sea. He is accompanied by his palace guard, an ornately clad retinue, and crowds of onlookers. The ruler and the dignitaries seated themselves, and were entertained by acrobats, jugglers, fire-eaters, and dancing girls in colorful silken, form-clinging diaphanous costumes. After the entertainment, American prisoners from the captured American frigate are dragged into the plaza. They were shackled and were flogged mercilessly by bearded and turbaned villains. While the prisoners were being prodded by swords and spears, boatloads of American marines approached the shore unseen, charged into the plaza, drove the enemy into the city, and freed the prisoners. American warships appeared and set the city afire with their cannon.

At the conclusion of the show and the grand fireworks finale, the capacity crowd would depart, some for Rice's Circus show nearby, some for a late snack in the coffee shop, some to the horseshoe-bar for a shot or two of moonshine, and some for home.

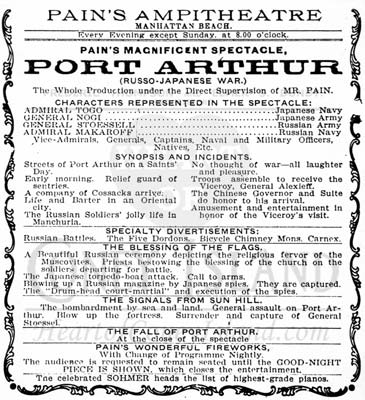

Port Arthur, a.k.a. Russo-Japanese War (1905)

The Russo-Japanese War began in February of 1904, and in January of 1905, the Japanese captured Port Arthur from the Russians. Even before the war had ended, Pain was already presenting Port Arthur at the Manhattan Beach stadium in the spring and summer of 1905.

Last Days of Pompeii, a.k.a. Vesuvius (1906)

Pain, in 1906, had a repeat of his old favorite, the Last Days of Pompeii, renaming it Vesuvius.

Battle of Cedar Creek, a.k.a. General Sheridan’s Ride (1907)

Pain's 1907 offering at Manhattan Beach was General Sheridan's Ride, or The Battle of Cedar Creek. This referred to an operation by the Union Army during the Civil War into the Shenandoah Valley, for the purpose of depriving the Confederate army of food by burning farms and farm products. Sheridan fought a battle at Cedar Creek with an enemy force led by General Early, defeated it, and burnt his way through the Shenandoah Valley. This gave Pain the opportunity to stage a battle scene, followed by the ensuing conflagration. Pain also presented, on the lagoon, his version of the battle between the Monitor and Merrimac.

The subject of Pain's show in 1901 was the Boxer Rebellion in China.

Burning of Rome (1902)

Early in 1902, after giving some thought as to his next presentation at Manhattan Beach, Pain decided to burn down Rome; not modern Rome, but that of the Emperor Nero.

As we know, Nero was an effete aesthete, blue-eyed and blond, and adept at acting, singing, dancing, poetical and musical composition, lyre-playing, and murder. As the story goes, one day, while standing on the balcony of his palace overlooking Rome, Nero asked himself the rhetorical question, ‘What am I emperor of?’ To which he answered, ‘I am emperor of the world.’ Yet, the capital of his empire was in his eyes an ugly, unsightly mess, an abomination called Rome. Nero decided that an emperor as noble and beautiful as himself should have a magnificent metropolis worthy of such a sublime being. Then and there, Nero decided to build a new city, and the quickest way of starting that urban-renewal project was to burn down the existing pile of rubbish.

Pain assigned his scenic artist, Kirby, to building a replica of ancient Rome. Nero's palace was placed at one side of a plaza on the shore of the lagoon, which represented the Tiber River. Hundreds of extras were fitted out in the uniforms of Roman legionnaires and praetorian guards, and taught to march to the cadence of beating cymbals and blaring trumpets. Hundreds of others were outfitted with togas and sandals to represent the populace of Rome. Robust types were chosen as gladiators, and instructed in how to duel with swords, spears, tridents, and nets.

At the first performance, ten thousand spectators filled the seats facing the Tibor and the City of Rome. They witnessed chariot races, marching troops, gladiatorial combats, and a colorful pageant. After the crowds had departed from the square, Nero, who had been watching the festivities from his balcony, pointed to the city, and out of the floor below men with flaming torches emerged, and rushed into Rome to set it afire. As the flames appeared in many quarters, Nero smiled, clapped his hands in delight, and did a little dance with arms aloft. Then, as the fires merged into one great conflagration, he picked up a violin and did a Paganini. Of course, there were no violins in Nero's time, so he must have plucked the strings of his lyre, but Pain was not one to fiddle with tradition. The show ended in a blaze of glory, with thousands of rockets lighting up the night sky. Had Nero witnessed the spectacle, he would have heaped honors on Pain; and then, for Pain's attempt to excel him in conflagrations, he certainly would have treated him to a hemlock cocktail.

Last Days of Pompeii (1903)

Before the 1903 season began, the Manhattan Beach management suggested to Pain that it might be economical to repeat some of his earlier shows. The scenery and sets of former shows were stored in warehouses and going to waste. Pain agreed, bringing back his first love, The Last Days of Pompeii, for the 1903 season. It broke all prior attendance records, with the Tammany Times reporting that 12,780 people attended on July Fourth, with another 8,000 being turned away at the gates for lack of room. The show ran nightly at 8 p.m.

Bombardment of Tripoli, a.k.a. Decatur’s Revenge (1904)

In planning his program for 1904, Pain became aware that it would be the 100th anniversary of the raid by Captain Stephen Decatur's marines on the port of Tripoli in Algeria (now in Libya). Decatur succeeded in burning the American frigate ‘Philadelphia’, which had been captured by the Barbary pirates.

Playing fast and loose with history, Pain had this event ending the war. During the show, the Bashaw, who was the ruler of Tripoli, entered the plaza in front of the city, on the shore of the Mediterranean Sea. He is accompanied by his palace guard, an ornately clad retinue, and crowds of onlookers. The ruler and the dignitaries seated themselves, and were entertained by acrobats, jugglers, fire-eaters, and dancing girls in colorful silken, form-clinging diaphanous costumes. After the entertainment, American prisoners from the captured American frigate are dragged into the plaza. They were shackled and were flogged mercilessly by bearded and turbaned villains. While the prisoners were being prodded by swords and spears, boatloads of American marines approached the shore unseen, charged into the plaza, drove the enemy into the city, and freed the prisoners. American warships appeared and set the city afire with their cannon.

At the conclusion of the show and the grand fireworks finale, the capacity crowd would depart, some for Rice's Circus show nearby, some for a late snack in the coffee shop, some to the horseshoe-bar for a shot or two of moonshine, and some for home.

Port Arthur, a.k.a. Russo-Japanese War (1905)

The Russo-Japanese War began in February of 1904, and in January of 1905, the Japanese captured Port Arthur from the Russians. Even before the war had ended, Pain was already presenting Port Arthur at the Manhattan Beach stadium in the spring and summer of 1905.

Last Days of Pompeii, a.k.a. Vesuvius (1906)

Pain, in 1906, had a repeat of his old favorite, the Last Days of Pompeii, renaming it Vesuvius.

Battle of Cedar Creek, a.k.a. General Sheridan’s Ride (1907)

Pain's 1907 offering at Manhattan Beach was General Sheridan's Ride, or The Battle of Cedar Creek. This referred to an operation by the Union Army during the Civil War into the Shenandoah Valley, for the purpose of depriving the Confederate army of food by burning farms and farm products. Sheridan fought a battle at Cedar Creek with an enemy force led by General Early, defeated it, and burnt his way through the Shenandoah Valley. This gave Pain the opportunity to stage a battle scene, followed by the ensuing conflagration. Pain also presented, on the lagoon, his version of the battle between the Monitor and Merrimac.

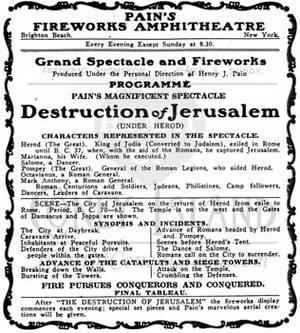

Destruction of Jerusalem, shown at Brighton Beach (1908)

Pain left Manhattan Beach for Brighton Beach Park in 1908 to present The Destruction of Jerusalem, by the Romans. This was shown in the stadium built by William A. Brady for his Boer War spectacle.

Battle in the Clouds, shown at Brighton Beach (1909)

Pain, still at Brighton Beach Park in 1909, presented a show called Battle in the Clouds. By this time there was great interest in aircraft and in its potential use in war. During World War I, people in coastal cities along the Atlantic feared that German zeppelins would cross the ocean and drop bombs on them. Pain’s show involved a battle between a dirigible and anti-aircraft guns firing blanks. The dirigible dropped what appeared to be bombs. Explosions on the ground, in which buildings were blown up, were caused by pre-set explosives detonated by electricity.

Battle of Gettysburg (1910)

Pain was back at Manhattan Beach in 1910 presenting the Battle of Gettysburg. This was his final season at Coney Island.

Pain after Coney Island (1911-1935)

For the first time in over thirty years, Henry Pain left Coney Island in 1911, never to return. His departure was symbolic of the declining fortunes of Manhattan Beach and Brighton Beach at the time. Recent changes in gambling laws made it illegal to bet on horse races in New York. The horse racetracks at Manhattan Beach and Brighton Beach tried hosting novelties such as automobile races, but these failed to attract the big-spending bettors and huge crowds that had come in years past. The great Manhattan Beach and Oriental hotels had trouble filling their rooms. Very soon, they would be out of business, and the Manhattan Beach and Brighton Beach of the prior thirty years would be gone forever.

When Pain left, his services were constantly in demand at various fairs and expositions. But the heyday for pyrotechnic shows was already starting to fade as well. Silent films were replacing traditional theater, and news updates featuring actual film footage from natural disasters were being shown before the main feature. The moving pictures would soon be presenting spectaculars that even Pain could not match. As early as 1911, Kinemacolor moving pictures were being presented at the Herald Square Theatre in Manhattan. It would not be too long before audiences would become too sophisticated to enjoy the elaborate reenactments had delighted them a generation earlier.

During World War I, Henry Pain made his explosives expertise available to the United States Government. He passed away in London on February 14, 1935, at the age of eighty, one of the few remaining figures who could be credited with having lived through and shaped Coney Island’s golden era from its very inception.

Pain left Manhattan Beach for Brighton Beach Park in 1908 to present The Destruction of Jerusalem, by the Romans. This was shown in the stadium built by William A. Brady for his Boer War spectacle.

Battle in the Clouds, shown at Brighton Beach (1909)

Pain, still at Brighton Beach Park in 1909, presented a show called Battle in the Clouds. By this time there was great interest in aircraft and in its potential use in war. During World War I, people in coastal cities along the Atlantic feared that German zeppelins would cross the ocean and drop bombs on them. Pain’s show involved a battle between a dirigible and anti-aircraft guns firing blanks. The dirigible dropped what appeared to be bombs. Explosions on the ground, in which buildings were blown up, were caused by pre-set explosives detonated by electricity.

Battle of Gettysburg (1910)

Pain was back at Manhattan Beach in 1910 presenting the Battle of Gettysburg. This was his final season at Coney Island.

Pain after Coney Island (1911-1935)

For the first time in over thirty years, Henry Pain left Coney Island in 1911, never to return. His departure was symbolic of the declining fortunes of Manhattan Beach and Brighton Beach at the time. Recent changes in gambling laws made it illegal to bet on horse races in New York. The horse racetracks at Manhattan Beach and Brighton Beach tried hosting novelties such as automobile races, but these failed to attract the big-spending bettors and huge crowds that had come in years past. The great Manhattan Beach and Oriental hotels had trouble filling their rooms. Very soon, they would be out of business, and the Manhattan Beach and Brighton Beach of the prior thirty years would be gone forever.

When Pain left, his services were constantly in demand at various fairs and expositions. But the heyday for pyrotechnic shows was already starting to fade as well. Silent films were replacing traditional theater, and news updates featuring actual film footage from natural disasters were being shown before the main feature. The moving pictures would soon be presenting spectaculars that even Pain could not match. As early as 1911, Kinemacolor moving pictures were being presented at the Herald Square Theatre in Manhattan. It would not be too long before audiences would become too sophisticated to enjoy the elaborate reenactments had delighted them a generation earlier.

During World War I, Henry Pain made his explosives expertise available to the United States Government. He passed away in London on February 14, 1935, at the age of eighty, one of the few remaining figures who could be credited with having lived through and shaped Coney Island’s golden era from its very inception.

This article combines the author's extensive ongoing research with the text of the late Manny Teitelman's unpublished manuscript, 'Coney Island, Last Stop!'

The manuscript's contents are used, modified and published under an exclusive copyright license dated 2016. All rights reserved.

[1] Image edited from original found at Library of Congress at: https://www.loc.gov/resource/pan.6a28056/

[2] Image from WikiMedia Commons at:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pain_of_London_fireworks,_Paris_and_the_Commune,_performance_poster,_Manhattan_Beach,_New_York,_1891.jpg

The manuscript's contents are used, modified and published under an exclusive copyright license dated 2016. All rights reserved.

[1] Image edited from original found at Library of Congress at: https://www.loc.gov/resource/pan.6a28056/

[2] Image from WikiMedia Commons at:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pain_of_London_fireworks,_Paris_and_the_Commune,_performance_poster,_Manhattan_Beach,_New_York,_1891.jpg

Return to Coney Island History Homepage