Coney Island History: How 'West Brighton' became 'Coney Island'

Introduction: The Rise of Coney Island as a Seaside Resort (1860-1900)

Today, people associate 'Coney Island’ with the amusements area around Surf Avenue and West 12th Street. This area, once known as West Brighton, is home to the Cyclone roller coaster, the Wonder Wheel, and other amusement rides. The rest of Coney Island, which includes Sea Gate to the west and both the Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach neighborhoods to the east, are residential areas.

In the early 1880s, however, Coney Island was just a sleepy farming community that had, almost overnight, transformed into a seaside resort destination. The entire 'island' was now filling up with hotels, music venues, restaurants, and private bathing houses that controlled certain sections of the beach.

At the time, several major investors and railroad companies had recently bought up large chunks of land at Coney Island. They then had spent millions of dollars building beautiful resorts on their properties, along with private railroads leading to them from Brooklyn. These three adjacent resorts - Brighton Beach, Manhattan Beach and West Brighton - would remain locked in a fierce battle for several decades.

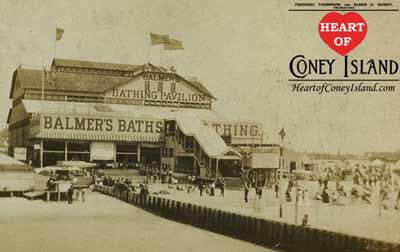

The Brighton Beach resort was just east of West Brighton. It was developed by a wealthy businessman named William Engeman, who teamed up with the Brooklyn, Flatbush and Coney Island Railroad. The primary attractions at Brighton Beach were the railroad company’s famous Brighton Beach Hotel, Engeman's Bathing Pavilion, the Brighton Beach Race Course and several other music, bathing and food venues. Brighton Beach tended to attract upper-middle class visitors.

The Manhattan Beach resort was just east of Brighton Beach, and even fancier. It boasted the luxurious Manhattan Beach Hotel and Oriental Hotel, offered concerts by renowned bands, and hosted the finest fireworks shows in the world. The Coney Island Jockey Club, a prominent social club, built a horse racing track adjacent to the Manhattan Beach Hotel. The Manhattan Beach resort was developed by a robber baron named Austin Corbin, who also ran several Brooklyn railroads. Manhattan Beach tended to attract wealthy people.

Lastly, there was the runt of the litter, our poor West Brighton. The amusement parks that would make West Brighton famous would not be built until around 1900. For now, scrappy little West Brighton did what it could. Two well-run railroad companies, one led by Andrew Culver and the other named the Sea Beach Company, developed the areas around their railroad terminals. They did not control all of the land at West Brighton, though, and other entrepreneurs set up businesses to serve mainly immigrant and working class clientele. It was a pleasant enough place, all things considered, but nothing like the deep-pocketed Brighton Beach or Manhattan Beach. So what, if some riffraff from neighboring Norton's Point, that undesirable spot at the far-western end of Coney island, occasionally stumbled into West Brighton saloons? Constable John McKane could take care of them. Still, let's be honest. Most people hanging out in West Brighton were dreaming that, one day, they could save up enough to patron Brighton Beach or Manhattan Beach.

This article is the comprehensive story of how West Brighton became 'Coney Island', and how it managed to eclipse both Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach between 1860 and 1920. It tells the stories of Andrew Culver, Paul Bauer, Charles Feltman and others who saw the potential of West Brighton and shaped its future. Another set of articles cover the iconic amusement parks that were built at West Brighton around 1900, namely Sea Lion Park, Steeplechase Park, Luna Park and Dreamland. By 1905, the term ‘Coney Island’ was largely synonymous with West Brighton and its amusement parks, an association that still endures to this day.

Today, people associate 'Coney Island’ with the amusements area around Surf Avenue and West 12th Street. This area, once known as West Brighton, is home to the Cyclone roller coaster, the Wonder Wheel, and other amusement rides. The rest of Coney Island, which includes Sea Gate to the west and both the Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach neighborhoods to the east, are residential areas.

In the early 1880s, however, Coney Island was just a sleepy farming community that had, almost overnight, transformed into a seaside resort destination. The entire 'island' was now filling up with hotels, music venues, restaurants, and private bathing houses that controlled certain sections of the beach.

At the time, several major investors and railroad companies had recently bought up large chunks of land at Coney Island. They then had spent millions of dollars building beautiful resorts on their properties, along with private railroads leading to them from Brooklyn. These three adjacent resorts - Brighton Beach, Manhattan Beach and West Brighton - would remain locked in a fierce battle for several decades.

The Brighton Beach resort was just east of West Brighton. It was developed by a wealthy businessman named William Engeman, who teamed up with the Brooklyn, Flatbush and Coney Island Railroad. The primary attractions at Brighton Beach were the railroad company’s famous Brighton Beach Hotel, Engeman's Bathing Pavilion, the Brighton Beach Race Course and several other music, bathing and food venues. Brighton Beach tended to attract upper-middle class visitors.

The Manhattan Beach resort was just east of Brighton Beach, and even fancier. It boasted the luxurious Manhattan Beach Hotel and Oriental Hotel, offered concerts by renowned bands, and hosted the finest fireworks shows in the world. The Coney Island Jockey Club, a prominent social club, built a horse racing track adjacent to the Manhattan Beach Hotel. The Manhattan Beach resort was developed by a robber baron named Austin Corbin, who also ran several Brooklyn railroads. Manhattan Beach tended to attract wealthy people.

Lastly, there was the runt of the litter, our poor West Brighton. The amusement parks that would make West Brighton famous would not be built until around 1900. For now, scrappy little West Brighton did what it could. Two well-run railroad companies, one led by Andrew Culver and the other named the Sea Beach Company, developed the areas around their railroad terminals. They did not control all of the land at West Brighton, though, and other entrepreneurs set up businesses to serve mainly immigrant and working class clientele. It was a pleasant enough place, all things considered, but nothing like the deep-pocketed Brighton Beach or Manhattan Beach. So what, if some riffraff from neighboring Norton's Point, that undesirable spot at the far-western end of Coney island, occasionally stumbled into West Brighton saloons? Constable John McKane could take care of them. Still, let's be honest. Most people hanging out in West Brighton were dreaming that, one day, they could save up enough to patron Brighton Beach or Manhattan Beach.

This article is the comprehensive story of how West Brighton became 'Coney Island', and how it managed to eclipse both Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach between 1860 and 1920. It tells the stories of Andrew Culver, Paul Bauer, Charles Feltman and others who saw the potential of West Brighton and shaped its future. Another set of articles cover the iconic amusement parks that were built at West Brighton around 1900, namely Sea Lion Park, Steeplechase Park, Luna Park and Dreamland. By 1905, the term ‘Coney Island’ was largely synonymous with West Brighton and its amusement parks, an association that still endures to this day.

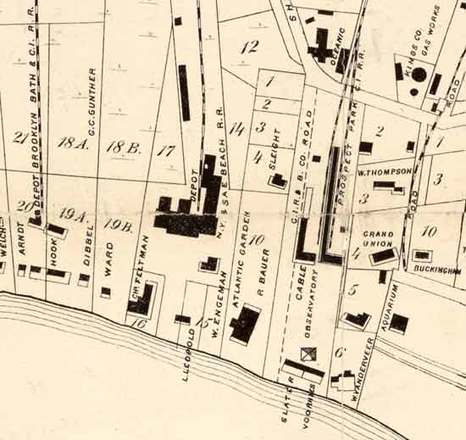

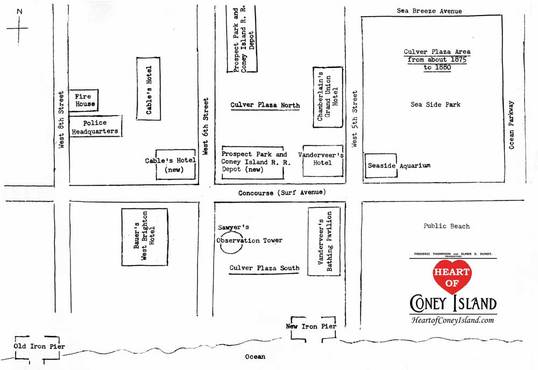

Use these maps to follow the story below.

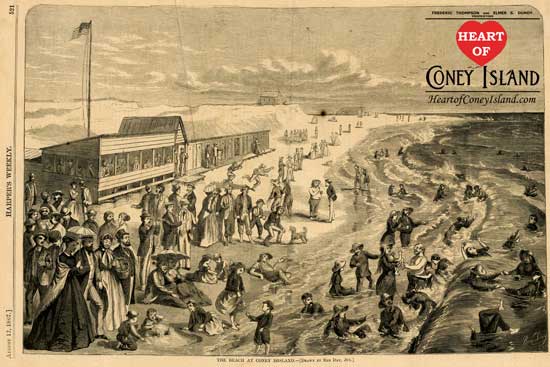

This drawing from 1867 shows that Coney Island was just a collection of sand dunes and shacks when the Gunther line was first built

This drawing from 1867 shows that Coney Island was just a collection of sand dunes and shacks when the Gunther line was first built

Coney Island’s First Railroad: Gunther’s ‘Dummy Line’ to West Brighton (1862)

The story of modern Coney Island can be traced back to a railroad construction boom that occurred shortly following the Civil War. Railroad companies at the time were scouring the northeast in search of desirable but undeveloped beachfront areas. Once they found a suitable location, they secured right-of-ways on which to lay track to it from a more populated area and purchased the beachfront property. The railroad companies also usually spruced up the beach terminal by building a nice hotel and plaza nearby, close to the water. Even though it required significant capital and a high degree of risk to vertically integrate like this, if the beach was a hit, the investment would pay off handsomely. The railroad would have a monopoly on transportation to the destination, capture all of the visitors’ spending on food and lodging, and also see its beachfront real estate appreciate significantly.

Coney Island already had a rather miserable little railroad ahead of the end of the Civil War. Built in 1862, it was officially called the Brooklyn, Bath, and Coney Island Railroad, but was better known as the ‘Gunther Line’ after its president, C. Godfrey Gunther. Its steam-powered locomotive that ran from a Bay Ridge pier to Bath Junction, then south through New Utrecht to Coney Island. Even though it was established primarily to collect agricultural and dairy products along the way for the New York markets, visitors coming from Manhattan used the Gunther Line during the summer bathing season to avoid the Norton's Point area at the western tip of Coney Island, which was filled with unsavory characters. The Gunther Line’s terminus was the Tivoli Hotel in West Brighton, which was in the vicinity of the present Stillwell and Surf Avenues. The Tivoli Hotel also had a restaurant. Further towards the beach were bathing facilities and a dance hall, owned by Gunther, and built by someone who later would come to run all of Coney Island, John Y. McKane.

The Gunther Line could have been a significant success and boon to the tourism business at West Brighton. Its only competition was a horse-car line that opened in 1860, traveling down Coney Island Road from Flatbush to what would become known as Brighton Beach. However, the Gunther Line trains, running at ground level, became involved in a number of accidents. The chugging locomotives and their shrieking whistles would cause frightened horses to bolt, overturning carriages. In New Utrecht, a regulation was enacted requiring a railroad employee to emerge from the train and walk in front of the slowly moving locomotive, ringing a bell, as the train passed through town. Onlookers laughed, passengers became irritated, and Gunther’s railroad earned the nickname, the ‘Dummy Line’. Coney Island’s development would have to wait over a decade, until a proper passenger railroad could bring crowds to the beach.

Ocean Parkway Attracts the Attention of Railroad Investors

After the Civil War, the wealthy residents of the city of Brooklyn used their political clout to have a spacious highway built from Prospect Park to the beach at Coney Island. At the time, there were only two roads to Coney Island's beaches, the Gravesend Road and the Coney Island Road. The former was a bit out of the way from the affluent sections of Brooklyn, while the latter was a horse-car line running along the middle of the road. Both sides of the rails were too rutted for a smooth ride and so they embarked on the new highway, to be built roughly midway between the existing roads. It was given the name of Ocean Boulevard, then changed to Ocean Parkway. It would be restricted to carriages and saddle-horses, with commercial and rail-traffic prohibited. Cinders, gravel, clay and a binder of tar were to ensure that the roadbed was not too hard on horses’ hooves, nor so soft for carriage wheels to sink in the mud.

The story of modern Coney Island can be traced back to a railroad construction boom that occurred shortly following the Civil War. Railroad companies at the time were scouring the northeast in search of desirable but undeveloped beachfront areas. Once they found a suitable location, they secured right-of-ways on which to lay track to it from a more populated area and purchased the beachfront property. The railroad companies also usually spruced up the beach terminal by building a nice hotel and plaza nearby, close to the water. Even though it required significant capital and a high degree of risk to vertically integrate like this, if the beach was a hit, the investment would pay off handsomely. The railroad would have a monopoly on transportation to the destination, capture all of the visitors’ spending on food and lodging, and also see its beachfront real estate appreciate significantly.

Coney Island already had a rather miserable little railroad ahead of the end of the Civil War. Built in 1862, it was officially called the Brooklyn, Bath, and Coney Island Railroad, but was better known as the ‘Gunther Line’ after its president, C. Godfrey Gunther. Its steam-powered locomotive that ran from a Bay Ridge pier to Bath Junction, then south through New Utrecht to Coney Island. Even though it was established primarily to collect agricultural and dairy products along the way for the New York markets, visitors coming from Manhattan used the Gunther Line during the summer bathing season to avoid the Norton's Point area at the western tip of Coney Island, which was filled with unsavory characters. The Gunther Line’s terminus was the Tivoli Hotel in West Brighton, which was in the vicinity of the present Stillwell and Surf Avenues. The Tivoli Hotel also had a restaurant. Further towards the beach were bathing facilities and a dance hall, owned by Gunther, and built by someone who later would come to run all of Coney Island, John Y. McKane.

The Gunther Line could have been a significant success and boon to the tourism business at West Brighton. Its only competition was a horse-car line that opened in 1860, traveling down Coney Island Road from Flatbush to what would become known as Brighton Beach. However, the Gunther Line trains, running at ground level, became involved in a number of accidents. The chugging locomotives and their shrieking whistles would cause frightened horses to bolt, overturning carriages. In New Utrecht, a regulation was enacted requiring a railroad employee to emerge from the train and walk in front of the slowly moving locomotive, ringing a bell, as the train passed through town. Onlookers laughed, passengers became irritated, and Gunther’s railroad earned the nickname, the ‘Dummy Line’. Coney Island’s development would have to wait over a decade, until a proper passenger railroad could bring crowds to the beach.

Ocean Parkway Attracts the Attention of Railroad Investors

After the Civil War, the wealthy residents of the city of Brooklyn used their political clout to have a spacious highway built from Prospect Park to the beach at Coney Island. At the time, there were only two roads to Coney Island's beaches, the Gravesend Road and the Coney Island Road. The former was a bit out of the way from the affluent sections of Brooklyn, while the latter was a horse-car line running along the middle of the road. Both sides of the rails were too rutted for a smooth ride and so they embarked on the new highway, to be built roughly midway between the existing roads. It was given the name of Ocean Boulevard, then changed to Ocean Parkway. It would be restricted to carriages and saddle-horses, with commercial and rail-traffic prohibited. Cinders, gravel, clay and a binder of tar were to ensure that the roadbed was not too hard on horses’ hooves, nor so soft for carriage wheels to sink in the mud.

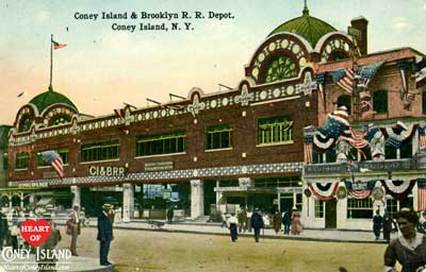

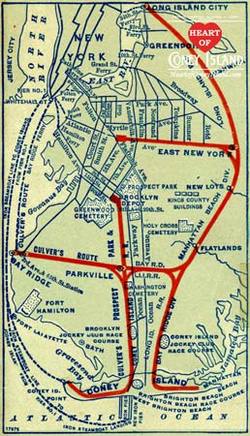

Map of the Culver Line's route

Map of the Culver Line's route

Culver builds the Prospect Park & Coney Island Railroad to West Brighton (1875)

Railroad tycoons and financiers learned of the plans for Ocean Parkway. Seeking ways to invest the fortunes they had made during the Civil War, they began toying with the notion that the beach area might be turned into a posh summer resort, like Saratoga, replete with race courses, plush hotels and elegant restaurants. When construction began of steel railroad bridges across Coney Island Creek at West 6th and West 8th Streets, and two others further east in the Middle Division and the Sedge Bank, it became obvious that Coney Island was about to have a major face-lift. Gunther's Dummy Line was due for some stiff competition.

Andrew Culver completed the Prospect Park and Coney Island Railroad to the West Brighton in 1875. It was commonly known as the Culver Line. Culver headed a syndicate that purchased franchises to build railroads from Brooklyn to Coney Island. The Culver Line had one branch running from the Bay Ridge Pier, the other from Prospect Park.

Culver caused quite a stir when his construction crews tore up Gravesend Avenue to lay rail. It had just been paved with a coat of smooth tar, and the local property owners had been assessed for the expense, as they stood to benefit the most from its improvement. Indignant residents demanded reimbursement, asking what benefit they would derive from the smoke-belching, roaring, iron monsters pounding by, destroying their peace and quiet. Politicians solemnly removed their hats, placed them over their hearts, observed a respectful minute of silence, and winked at Culver. In later years, when the Culver Line became part of the Brooklyn Rapid Transit system, an elevated railway was built along this avenue.

Culver Plaza North (1875)

Culver established a vibrant and welcoming plaza in West Brighton to attract visitors. Known as Culver Plaza, it was situated next to a terminal he built in a large vacant area between West 5th and West 6th Streets, into which both branches of the Culver Line ran south along Gravesend Avenue.

Railroad tycoons and financiers learned of the plans for Ocean Parkway. Seeking ways to invest the fortunes they had made during the Civil War, they began toying with the notion that the beach area might be turned into a posh summer resort, like Saratoga, replete with race courses, plush hotels and elegant restaurants. When construction began of steel railroad bridges across Coney Island Creek at West 6th and West 8th Streets, and two others further east in the Middle Division and the Sedge Bank, it became obvious that Coney Island was about to have a major face-lift. Gunther's Dummy Line was due for some stiff competition.

Andrew Culver completed the Prospect Park and Coney Island Railroad to the West Brighton in 1875. It was commonly known as the Culver Line. Culver headed a syndicate that purchased franchises to build railroads from Brooklyn to Coney Island. The Culver Line had one branch running from the Bay Ridge Pier, the other from Prospect Park.

Culver caused quite a stir when his construction crews tore up Gravesend Avenue to lay rail. It had just been paved with a coat of smooth tar, and the local property owners had been assessed for the expense, as they stood to benefit the most from its improvement. Indignant residents demanded reimbursement, asking what benefit they would derive from the smoke-belching, roaring, iron monsters pounding by, destroying their peace and quiet. Politicians solemnly removed their hats, placed them over their hearts, observed a respectful minute of silence, and winked at Culver. In later years, when the Culver Line became part of the Brooklyn Rapid Transit system, an elevated railway was built along this avenue.

Culver Plaza North (1875)

Culver established a vibrant and welcoming plaza in West Brighton to attract visitors. Known as Culver Plaza, it was situated next to a terminal he built in a large vacant area between West 5th and West 6th Streets, into which both branches of the Culver Line ran south along Gravesend Avenue.

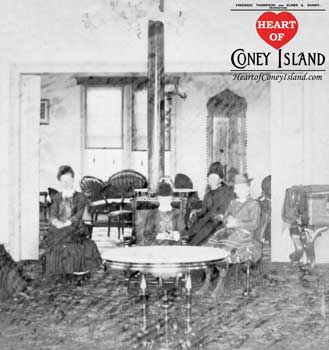

Vanderveer's parlor shows it was functional. For luxury, one had to go to Manhattan Beach.

Vanderveer's parlor shows it was functional. For luxury, one had to go to Manhattan Beach.

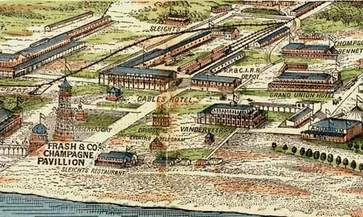

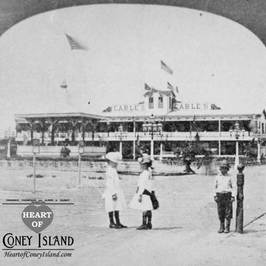

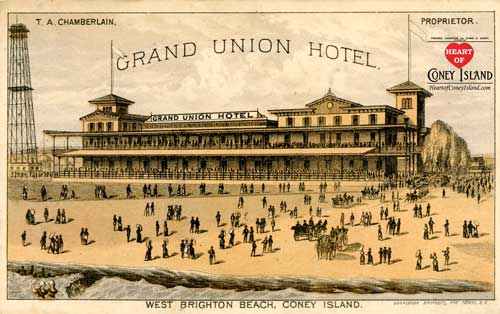

Culver Plaza North was separated from Culver Plaza South by Surf Avenue, which at the time was known as the Concourse. Initially, only Culver Plaza North was developed. It was bounded by the railroad depot at its northern end, by Cable’s Hotel on the western side, and by Vanderveer’s Hotel and Chamberlain’s Grand Union Hotel along the eastern side at West 5th Street. Culver Plaza North was decorated with urns, fountains and flower beds. It also had refreshment kiosks, a small variety theater named the Elliott, and an enclosure for a camera obscura. The latter was a popular and clever device that used numerous mirrors to project real-time images of people and places from the beach and other outdoor areas onto a concave screen in a darkened room, almost like a movie.

Culver relied in particular on Thomas Cable’s prior experience in running a hotel at Coney Island to make the plaza a success. While Culver's railroad was still in its planning stage, Culver had consulted Cable about the viability of opening a hotel in the plaza. Cable knew that hotels at Coney Island were tricky because of the seasonality and limited number of visitors at this time, but thought he could make it work with Culver’s railroad traffic. Cable accepted a lease from Culver at a very reasonable rate on a hotel that Culver built for him. Cable’s Hotel opened for business well before the railroad did. Only men were permitted to stay at the hotel, but women and children were welcome to dine in its restaurant. Cable seemed to have in mind an English style gentlemen's club, in which they could drink their whiskies and soda, smoke their cigars, read their newspapers, and discuss business, politics, sports, and show girls. Cable was also said to have had the best wine cellar in Coney Island.

Cable's Hotel ended up being a hit in its first season, and its restaurant were filled to capacity. In front of Cable’s Hotel, in the plaza, were a bandstand and benches that Cable’s installed to provide general entertainment for visitors to Culver Plaza North. People coming off Culver's trains were entertained by Downing's 9th Regimental Band, and the aroma of savory dishes coming from the dining room had crowds waiting on line to enter.

Culver relied in particular on Thomas Cable’s prior experience in running a hotel at Coney Island to make the plaza a success. While Culver's railroad was still in its planning stage, Culver had consulted Cable about the viability of opening a hotel in the plaza. Cable knew that hotels at Coney Island were tricky because of the seasonality and limited number of visitors at this time, but thought he could make it work with Culver’s railroad traffic. Cable accepted a lease from Culver at a very reasonable rate on a hotel that Culver built for him. Cable’s Hotel opened for business well before the railroad did. Only men were permitted to stay at the hotel, but women and children were welcome to dine in its restaurant. Cable seemed to have in mind an English style gentlemen's club, in which they could drink their whiskies and soda, smoke their cigars, read their newspapers, and discuss business, politics, sports, and show girls. Cable was also said to have had the best wine cellar in Coney Island.

Cable's Hotel ended up being a hit in its first season, and its restaurant were filled to capacity. In front of Cable’s Hotel, in the plaza, were a bandstand and benches that Cable’s installed to provide general entertainment for visitors to Culver Plaza North. People coming off Culver's trains were entertained by Downing's 9th Regimental Band, and the aroma of savory dishes coming from the dining room had crowds waiting on line to enter.

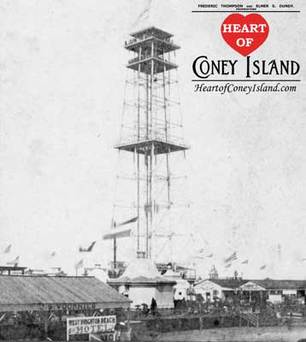

Great photo of Iron Tower showing Voorhies Pavilion at the front left and sign for Bauer's Hotel

Great photo of Iron Tower showing Voorhies Pavilion at the front left and sign for Bauer's Hotel

Culver Plaza South and Iron Tower Observatory (1876)

At the end of the following season, Culver decided to make some significant changes to Culver Plaza. Overall, Culver felt that his railroad depot was too far from the Concourse, which was the area’s main thoroughfare, and much too far from the beach. So, he tore up Culver Plaza North and moved the heart of it to Culver Plaza South, which was on the beach side of the Concourse.

Culver built a new terminal at the southern end of Culver Plaza North, along the Concourse, between West 5th and West 6th Streets. He also demolished some structures in Culver Plaza North, brought others to Culver Plaza South, and extended the tracks southward through the old plaza to the new depot. This destroyed the prior aura of spaciousness and charm that characterized Culver Plaza North.

Cable’s Hotel now faced railroad tracks instead of an open plaza. Therefore, a new Cable Hotel was built on the west side of the depot facing the Concourse, with West 6th Street between it and the original Cable’s Hotel. The old Cable’s Hotel, forming a right angle with the new one, remained as an annex to handle the overflow crowd of the new hotel. Cable did not renew his lease, and it was acquired by Doyle and Stubenbord, who changed the name of the new hotel to the Ocean View Hotel, and the old one to Doyle's Annex. In later years, the new structure was renamed the Prospect Hotel.

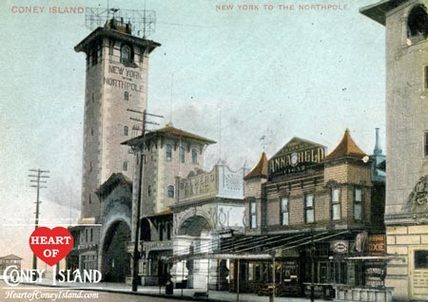

Also in 1876, Philadelphia hosted a massive fair to commemorate the Centennial of the Declaration of Independence. Many architecturally advanced buildings were constructed to house exhibits and showcase technological advances. Culver purchased one of the main attractions, Sawyer's Observation Tower, and re-erected it at Culver Plaza South. Often called Iron Tower, Steel Tower or the Iron Observatory, it was a steel structure that stood 300 feet high, an incredible height at the time. Two steam elevators that carried passengers to a platform at the top, where visitors could use telescopes to have a forty-mile panoramic view. People loved these views at a time before skyscrapers or airplanes had been invented.

Culver also built a rail extension to the pier at Norton's Point to connect West Brighton with steamers landing there. Its tracks were along Railroad Avenue, which was about thirty yards north of Surf Avenue, and ran parallel to it. Throughout the following decade, Culver would prove his mettle time and again. His railroad would become known as the best run on Coney Island.

At the end of the following season, Culver decided to make some significant changes to Culver Plaza. Overall, Culver felt that his railroad depot was too far from the Concourse, which was the area’s main thoroughfare, and much too far from the beach. So, he tore up Culver Plaza North and moved the heart of it to Culver Plaza South, which was on the beach side of the Concourse.

Culver built a new terminal at the southern end of Culver Plaza North, along the Concourse, between West 5th and West 6th Streets. He also demolished some structures in Culver Plaza North, brought others to Culver Plaza South, and extended the tracks southward through the old plaza to the new depot. This destroyed the prior aura of spaciousness and charm that characterized Culver Plaza North.

Cable’s Hotel now faced railroad tracks instead of an open plaza. Therefore, a new Cable Hotel was built on the west side of the depot facing the Concourse, with West 6th Street between it and the original Cable’s Hotel. The old Cable’s Hotel, forming a right angle with the new one, remained as an annex to handle the overflow crowd of the new hotel. Cable did not renew his lease, and it was acquired by Doyle and Stubenbord, who changed the name of the new hotel to the Ocean View Hotel, and the old one to Doyle's Annex. In later years, the new structure was renamed the Prospect Hotel.

Also in 1876, Philadelphia hosted a massive fair to commemorate the Centennial of the Declaration of Independence. Many architecturally advanced buildings were constructed to house exhibits and showcase technological advances. Culver purchased one of the main attractions, Sawyer's Observation Tower, and re-erected it at Culver Plaza South. Often called Iron Tower, Steel Tower or the Iron Observatory, it was a steel structure that stood 300 feet high, an incredible height at the time. Two steam elevators that carried passengers to a platform at the top, where visitors could use telescopes to have a forty-mile panoramic view. People loved these views at a time before skyscrapers or airplanes had been invented.

Culver also built a rail extension to the pier at Norton's Point to connect West Brighton with steamers landing there. Its tracks were along Railroad Avenue, which was about thirty yards north of Surf Avenue, and ran parallel to it. Throughout the following decade, Culver would prove his mettle time and again. His railroad would become known as the best run on Coney Island.

Merritt's trade advertised an 'oceanfront' Sea Beach Palace

Merritt's trade advertised an 'oceanfront' Sea Beach Palace

Culver’s Competition: The Sea Beach Railroad opens Sea Beach Palace at West Brighton (1878)

Culver was the first to reach West Brighton, but was not alone in seeing the area’s potential. At around the time that Culver was bringing his Prospect Park and Coney Island Railroad to West 6th Street and the Concourse, a competing company decided to enter the fray at West Brighton.

The New York and Sea Beach Railroad was organized by a syndicate headed by the Lorillard tobacco people. They acquired a vacant tract just to the west of Culver’s tract. It ran between West 8th to West 12th Streets, from Surf to Neptune Avenues. Because this tract had no oceanfront access, they also purchased a strip of land near West 8th Street between Surf Avenue and the ocean. Their Sea Beach Railroad ran between the Bay Ridge Pier and a terminal that was at the present Surf Avenue and West 10th Street.

The Sea Beach Railroad executives, realizing that Culver was no pushover, also went shopping at the Philadelphia Centennial for a signature building to attract visitors. They purchased the fair’s United States Government building, intending it to serve as the Sea Beach Railroad’s West Brighton terminal at West 10th Street. The building was renamed Sea Beach Palace and moved to Coney Island in late 1876, re-erected during 1877, and opened in May of 1878.

Sea Beach Palace was a beautiful and massive steel-and-glass structure centered around a grand glass dome. It served both as a terminal and a large indoor entertainment facility. Large or tall

buildings were considered particularly special at the time because of the unique architectural challenges back then, especially those with large glass domes. The main floor of the building had, in addition to the trains’ waiting room, a large restaurant, bar, theatre, convention hall, and exhibition rooms. Sandwiches, cold cuts and salads were served at a lunch counter that was 240 feet long. When the convention hall was not being used, it became a roller-skating rink, with music provided for the skaters. The upper floor initially served as a hotel, with accommodations for two hundred guests. The noise from the crowds and trains below, in addition to the smoke from the locomotives, resulted in empty rooms. Eventually, the upper-floor rooms were converted into railroad and telegraph offices.

Even though trade card advertisements frequently show people bathing in front of Sea Beach Palace, it was on the opposite side of the Concourse from the ocean, and never that close to the beach. So much for the morality of Charles Merritt, its prim-and-proper Victorian-era manager!

Sea Beach Palace would remain an iconic landmark at West Brighton for decades. Over time, it would be among several destinations that would perpetuate a gradual shift westward of the center of West Brighton, away from Culver Plaza.

Culver was the first to reach West Brighton, but was not alone in seeing the area’s potential. At around the time that Culver was bringing his Prospect Park and Coney Island Railroad to West 6th Street and the Concourse, a competing company decided to enter the fray at West Brighton.

The New York and Sea Beach Railroad was organized by a syndicate headed by the Lorillard tobacco people. They acquired a vacant tract just to the west of Culver’s tract. It ran between West 8th to West 12th Streets, from Surf to Neptune Avenues. Because this tract had no oceanfront access, they also purchased a strip of land near West 8th Street between Surf Avenue and the ocean. Their Sea Beach Railroad ran between the Bay Ridge Pier and a terminal that was at the present Surf Avenue and West 10th Street.

The Sea Beach Railroad executives, realizing that Culver was no pushover, also went shopping at the Philadelphia Centennial for a signature building to attract visitors. They purchased the fair’s United States Government building, intending it to serve as the Sea Beach Railroad’s West Brighton terminal at West 10th Street. The building was renamed Sea Beach Palace and moved to Coney Island in late 1876, re-erected during 1877, and opened in May of 1878.

Sea Beach Palace was a beautiful and massive steel-and-glass structure centered around a grand glass dome. It served both as a terminal and a large indoor entertainment facility. Large or tall

buildings were considered particularly special at the time because of the unique architectural challenges back then, especially those with large glass domes. The main floor of the building had, in addition to the trains’ waiting room, a large restaurant, bar, theatre, convention hall, and exhibition rooms. Sandwiches, cold cuts and salads were served at a lunch counter that was 240 feet long. When the convention hall was not being used, it became a roller-skating rink, with music provided for the skaters. The upper floor initially served as a hotel, with accommodations for two hundred guests. The noise from the crowds and trains below, in addition to the smoke from the locomotives, resulted in empty rooms. Eventually, the upper-floor rooms were converted into railroad and telegraph offices.

Even though trade card advertisements frequently show people bathing in front of Sea Beach Palace, it was on the opposite side of the Concourse from the ocean, and never that close to the beach. So much for the morality of Charles Merritt, its prim-and-proper Victorian-era manager!

Sea Beach Palace would remain an iconic landmark at West Brighton for decades. Over time, it would be among several destinations that would perpetuate a gradual shift westward of the center of West Brighton, away from Culver Plaza.

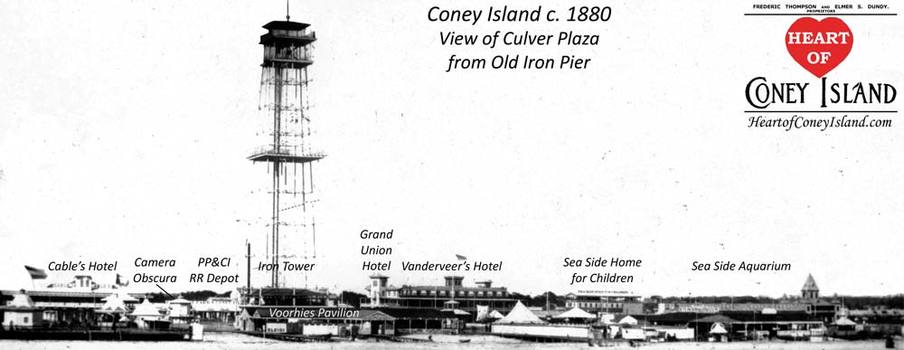

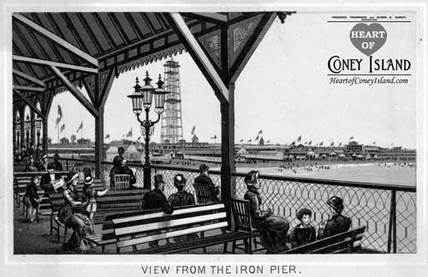

View of Culver Plaza and West Brighton from the Iron Pier c. 1881

View of Culver Plaza and West Brighton from the Iron Pier c. 1881

The Sea Beach Railroad builds the Iron Pier (1879)

The New York and Sea Beach Railroad Company decided, early in 1879, to construct an iron pier at the beach in front of its oceanfront West 8th Street property. Its subsidiary, the Ocean Pier and Navigation Company, supervised the construction of the pier, and operated it after its completion in the summer of 1879. The pier extended from 1,000 to 1,300 feet (accounts of its length vary) into the ocean, where steamboats discharged, or took on, passengers. It had two covered decks, or levels, fifty feet wide at the narrowest parts, and 125 feet wide at it broadest parts, which were near both ends of the pier, and in the middle. On the upper floor, at the three broad sections, were pagoda-like structures forty feet high, containing a restaurant, ballroom, and a theatre with 2,500 seats. Eventually, the entire upper level was covered by superstructures housing a beauty salon, tonsorial parlor, florist, pharmacy, confectionary shop, cigar store, lounges, newsstand, and some company offices. The offshore section of the pier had side-sliding windows to protest against inclement weather. There were hundreds of gas lamps, in clusters, and covered with colored globes, along both levels of the pier. Steamboat passengers used the lower level, which had benches on both sides to accommodate those waiting for, or emerging from, boats. It also had refreshment stands, an ice cream parlor, and, near the shore, locker rooms for those wishing to bathe. Later, these bathhouses were moved off the pier and onto shore. The pier was connected to Surf Avenue by a paved lane called Sea Beach Walk. Years later, when Dreamland was built, this pier became known as Dreamland Pier.

The New York and Sea Beach Railroad Company decided, early in 1879, to construct an iron pier at the beach in front of its oceanfront West 8th Street property. Its subsidiary, the Ocean Pier and Navigation Company, supervised the construction of the pier, and operated it after its completion in the summer of 1879. The pier extended from 1,000 to 1,300 feet (accounts of its length vary) into the ocean, where steamboats discharged, or took on, passengers. It had two covered decks, or levels, fifty feet wide at the narrowest parts, and 125 feet wide at it broadest parts, which were near both ends of the pier, and in the middle. On the upper floor, at the three broad sections, were pagoda-like structures forty feet high, containing a restaurant, ballroom, and a theatre with 2,500 seats. Eventually, the entire upper level was covered by superstructures housing a beauty salon, tonsorial parlor, florist, pharmacy, confectionary shop, cigar store, lounges, newsstand, and some company offices. The offshore section of the pier had side-sliding windows to protest against inclement weather. There were hundreds of gas lamps, in clusters, and covered with colored globes, along both levels of the pier. Steamboat passengers used the lower level, which had benches on both sides to accommodate those waiting for, or emerging from, boats. It also had refreshment stands, an ice cream parlor, and, near the shore, locker rooms for those wishing to bathe. Later, these bathhouses were moved off the pier and onto shore. The pier was connected to Surf Avenue by a paved lane called Sea Beach Walk. Years later, when Dreamland was built, this pier became known as Dreamland Pier.

Culver Responds by building the New Iron Pier (1881)

Two years later, the Culver Company, through its subsidiary, the Brighton Pier and Navigation Company, constructed its own iron pier, at about West 5th Street, extending 1,500 feet out into the ocean, and built a brick walk from Culver Plaza South towards the pier. Unlike the Iron Pier, this New Iron Pier had only one covered level, but at each end it had two massive superstructures 150 feet wide. On the upper level at the ocean end was a theatre, and at the shore end, a restaurant and ballroom, along with the additional civilized amenities provided at the other pier. Culver's pier became known as 'New Iron Pier' and the original Sea Beach Iron Pier became known as 'Old' Iron Pier (and, eventually, Dreamland Pier). At both piers, military bands would greet passengers arriving in steamboats, and dance bands would alternate between the ballrooms and theatres. In the latter, variety acts were presented.

Two years later, the Culver Company, through its subsidiary, the Brighton Pier and Navigation Company, constructed its own iron pier, at about West 5th Street, extending 1,500 feet out into the ocean, and built a brick walk from Culver Plaza South towards the pier. Unlike the Iron Pier, this New Iron Pier had only one covered level, but at each end it had two massive superstructures 150 feet wide. On the upper level at the ocean end was a theatre, and at the shore end, a restaurant and ballroom, along with the additional civilized amenities provided at the other pier. Culver's pier became known as 'New Iron Pier' and the original Sea Beach Iron Pier became known as 'Old' Iron Pier (and, eventually, Dreamland Pier). At both piers, military bands would greet passengers arriving in steamboats, and dance bands would alternate between the ballrooms and theatres. In the latter, variety acts were presented.

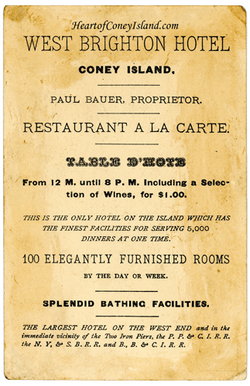

Ad for Bauer's West Brighton Hotel

Ad for Bauer's West Brighton Hotel

Paul Bauer establishes his West Brighton Beach Hotel (1876)

While Culver and the Sea Beach Railroad were battling it out, but before they had built their iron piers, a genial man by the name of Paul Bauer entered the scene. Bauer had emigrated from Austria to the United States and risen to the rank of captain in the Union Army during the Civil War.

According to William Stillwell, a descendant of one of Gravesend's settlers, Bauer and his wife were visiting West Brighton in early 1876. The Concourse (Surf Avenue) was not yet paved, and they were having difficulty driving their horse and carriage along the road’s deep sand. Bauer’s wife remarked that it was the worst place she had ever seen, to which Bauer responded that it could be made the best place. The following day, he obtained the twelve-acre lease there from Gravesend Township and began to execute his vision.

This fanciful account doesn't quite square with allegations that Bauer got the property for considerably less than others were offering for it. Bauer's daughter was the wife of John McKane's younger brother, James. John McKane was a crooked and increasingly powerful local politician who, by 1876, was responsible for many aspects of Gravesend’s local government operations, including renting out the Gravesend common lands. There is every reason to believe that Bauer's acquisition of this valuable tract was due not to a spontaneous decision by him, but to a good deal of finagling by John McKane prior to the transaction.

Paul Bauer’s lease was, in any case, stellar. It was a long-term lease on land between West 6th and West 8th Streets, from the Concourse all the way down to the ocean. The property was ideally situated between the two new railroad terminals across the Concourse, and, later, between the iron piers.

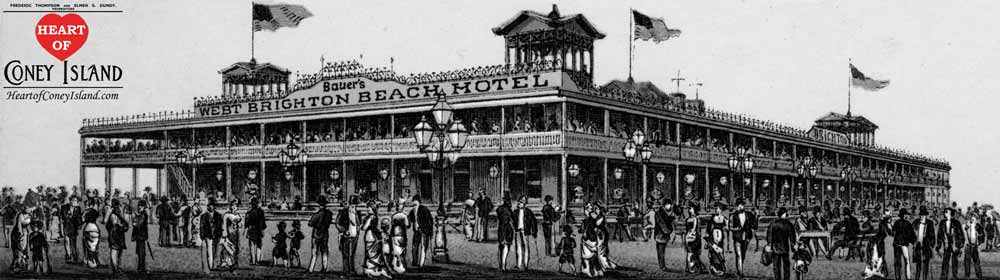

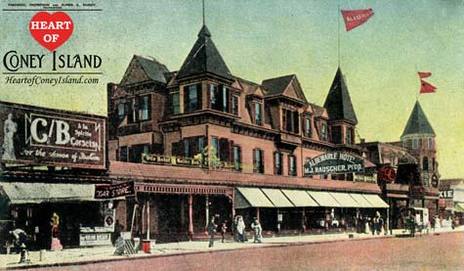

Bauer began dreaming plans to build a grand hotel on his tract that would put Cable’s, Vanderveer’s, Chamberlain’s and the others to shame. The McKane Construction Company was given the construction contract, unsurprisingly, as this was John McKane’s favorite method of receiving kickbacks for doling out leases at below market prices. The hotel would be a two-story, all-frame structure. It measured about 250 feet in a north-south direction, and about 150 along the Concourse. There were verandas (at the time called piazzas) on each level that extended completely around the building. On the roof of the building, at each corner, were towers with private dining-rooms for coaching parties, or groups of people using them to celebrate special occasions.

Bauer’s Atlantic Garden Hotel, later renamed the West Brighton Beach Hotel, opened in May of 1876. It was an instant success. Its location was outstanding, right next to the Iron Tower observatory. And yes, he actually did have an oceanfront hotel, unlike those lying scoundrels at Sea Beach Palace. The hotel was illuminated by thousands of gas-jets in colored globes, and Chinese, or Japanese, lanterns were strung around the grounds, imparting a festiveness to the area. The upper floors provided hotel facilities for two hundred guests, and the main floor had a restaurant that could serve eight-thousand diners at one time, with room on the verandas for 2,000 more. Also on the main floor was a bar, where prodigious amounts of beer were dispensed and consumed. The basement is said to have contained 20,000 bottles of wine and whiskey. Also in the basement was a billiard room, and a shooting range that presumably not in proximity to the bottles. On the south side of the hotel was a bandstand, where the Red Hussar Band, appropriately dressed in uniforms, entertained the crowds there, said to number often over twenty-five thousand people.

While Culver and the Sea Beach Railroad were battling it out, but before they had built their iron piers, a genial man by the name of Paul Bauer entered the scene. Bauer had emigrated from Austria to the United States and risen to the rank of captain in the Union Army during the Civil War.

According to William Stillwell, a descendant of one of Gravesend's settlers, Bauer and his wife were visiting West Brighton in early 1876. The Concourse (Surf Avenue) was not yet paved, and they were having difficulty driving their horse and carriage along the road’s deep sand. Bauer’s wife remarked that it was the worst place she had ever seen, to which Bauer responded that it could be made the best place. The following day, he obtained the twelve-acre lease there from Gravesend Township and began to execute his vision.

This fanciful account doesn't quite square with allegations that Bauer got the property for considerably less than others were offering for it. Bauer's daughter was the wife of John McKane's younger brother, James. John McKane was a crooked and increasingly powerful local politician who, by 1876, was responsible for many aspects of Gravesend’s local government operations, including renting out the Gravesend common lands. There is every reason to believe that Bauer's acquisition of this valuable tract was due not to a spontaneous decision by him, but to a good deal of finagling by John McKane prior to the transaction.

Paul Bauer’s lease was, in any case, stellar. It was a long-term lease on land between West 6th and West 8th Streets, from the Concourse all the way down to the ocean. The property was ideally situated between the two new railroad terminals across the Concourse, and, later, between the iron piers.

Bauer began dreaming plans to build a grand hotel on his tract that would put Cable’s, Vanderveer’s, Chamberlain’s and the others to shame. The McKane Construction Company was given the construction contract, unsurprisingly, as this was John McKane’s favorite method of receiving kickbacks for doling out leases at below market prices. The hotel would be a two-story, all-frame structure. It measured about 250 feet in a north-south direction, and about 150 along the Concourse. There were verandas (at the time called piazzas) on each level that extended completely around the building. On the roof of the building, at each corner, were towers with private dining-rooms for coaching parties, or groups of people using them to celebrate special occasions.

Bauer’s Atlantic Garden Hotel, later renamed the West Brighton Beach Hotel, opened in May of 1876. It was an instant success. Its location was outstanding, right next to the Iron Tower observatory. And yes, he actually did have an oceanfront hotel, unlike those lying scoundrels at Sea Beach Palace. The hotel was illuminated by thousands of gas-jets in colored globes, and Chinese, or Japanese, lanterns were strung around the grounds, imparting a festiveness to the area. The upper floors provided hotel facilities for two hundred guests, and the main floor had a restaurant that could serve eight-thousand diners at one time, with room on the verandas for 2,000 more. Also on the main floor was a bar, where prodigious amounts of beer were dispensed and consumed. The basement is said to have contained 20,000 bottles of wine and whiskey. Also in the basement was a billiard room, and a shooting range that presumably not in proximity to the bottles. On the south side of the hotel was a bandstand, where the Red Hussar Band, appropriately dressed in uniforms, entertained the crowds there, said to number often over twenty-five thousand people.

The Atlantic Garden dining-room was the talk of the town. All its walls were papered with seascapes and landscapes, showing nature in different seasons and moods, such as snow-capped mountains, waterfalls, raging seas, or placid lakes amid flowering meadows. The ceiling was painted gold, and crystal chandeliers endowed the room with an ornate glow. Contributing further to its elegance was an orchestra composed of thirty young female musicians attired in white gowns. Bauer had brought this orchestra from his native Vienna, along with its conductor, Marie Roller, who was also a violin soloist. In such ambiance, even if the food had been poor, it would have been enjoyed, but it was of first class quality, well prepared, and ample in its portions. The desserts of Viennese pastries provided their subtle addition to expanding waistlines.

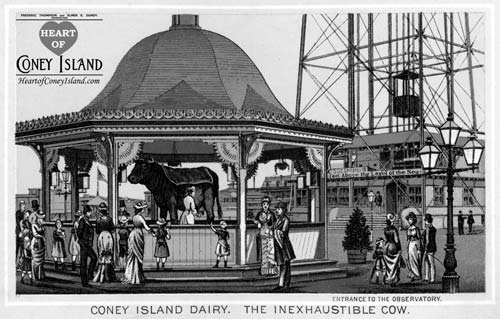

About a year after Bauer opened his hotel, he got McKane’s carpenters to construct a platform on the east and south sides of the hotel. The platform on the east reached to the pedestrian walk leading from Culver Plaza South to the shore, and the platform on the south extended southward for about 350 feet to where stairs led to the beach. On the platform east of the hotel, tables and benches were placed for the convenience of picnickers. Nearby was a kiosk that housed a large, artificial cow. Pretty milkmaids, serving customers, drew from the cow's udder not only cold milk, sarsaparilla and beer, but champagne and other liquid refreshments. The creature was known as the Inexhaustible Cow.

As fast as Bauer was making money, he was pouring it back into the business. After a few years, Bauer expanded the hotel, adding additional rooms on the roof and connecting them to the tower dining-rooms. To the southwest of his hotel, McKane also built for him a huge structure which he intended to use as a theatre, a ballroom, or a convention hall. It was called Bauer's Casino. As we shall see, it was eventually repurposed into the Coney Island Athletic Club, the famous sports arena in which ‘Gentleman’ Jim Corbett, Bob Fitzsimmons, and Jim Jeffries fought for the heavyweight boxing championship of the world.

Bauer made other improvements, such as carriage houses and stables for his wealthy guests, and an exclusive clubhouse for them on the north side of the Concourse, opposite his hotel. Bauer was spending on such a lavish scale that he had to borrow extensively, expecting that the returns on his investments would greatly exceed his costs. In his business, as in farming, success depended to a great extent on the weather, and often the weather failed to cooperate. As we shall see, poor Paul Bauer had gone in over his head in debt.

About a year after Bauer opened his hotel, he got McKane’s carpenters to construct a platform on the east and south sides of the hotel. The platform on the east reached to the pedestrian walk leading from Culver Plaza South to the shore, and the platform on the south extended southward for about 350 feet to where stairs led to the beach. On the platform east of the hotel, tables and benches were placed for the convenience of picnickers. Nearby was a kiosk that housed a large, artificial cow. Pretty milkmaids, serving customers, drew from the cow's udder not only cold milk, sarsaparilla and beer, but champagne and other liquid refreshments. The creature was known as the Inexhaustible Cow.

As fast as Bauer was making money, he was pouring it back into the business. After a few years, Bauer expanded the hotel, adding additional rooms on the roof and connecting them to the tower dining-rooms. To the southwest of his hotel, McKane also built for him a huge structure which he intended to use as a theatre, a ballroom, or a convention hall. It was called Bauer's Casino. As we shall see, it was eventually repurposed into the Coney Island Athletic Club, the famous sports arena in which ‘Gentleman’ Jim Corbett, Bob Fitzsimmons, and Jim Jeffries fought for the heavyweight boxing championship of the world.

Bauer made other improvements, such as carriage houses and stables for his wealthy guests, and an exclusive clubhouse for them on the north side of the Concourse, opposite his hotel. Bauer was spending on such a lavish scale that he had to borrow extensively, expecting that the returns on his investments would greatly exceed his costs. In his business, as in farming, success depended to a great extent on the weather, and often the weather failed to cooperate. As we shall see, poor Paul Bauer had gone in over his head in debt.

Charles Feltman c. 1884

Charles Feltman c. 1884

Charles Feltman transforms West Brighton’s Dining and Entertainment Scene (1875)

Around 1870, a good five years before Culver entered the picture, Charles Feltman had a wholesale bakery in the Park Slope area of Brooklyn that was supplying bread, cake, and ice cream to the small hotels, food stands, and bathing pavilions that made up Coney Island in its early days. Feltman was a German immigrant who had come to America at a young age in search of opportunity. He had endured initial hardship, saved enough to become his own boss, and was now a capable businessman who was willing to take calculated risks. One of those risks had been his Brooklyn bakery, which he built in a then-undeveloped area on the expectation that southern Brooklyn would develop. His gamble paid off, and by the early 1870s, he was supplying two out of three bakery products sold at Coney Island.

For the 1875 season, Feltman established his own dining establishment directly in West Brighton, while still maintaining his wholesale bakery. He correctly estimated that the new venture would be quite profitable, based on the volumes his customers were ordering and the markups they were able to charge. Feltman leased a 16 foot by 25 foot shanty around Culver Plaza, erected a basic but more respectable lunch stand roughly double its size adjacent to it, and began quality clam roasts, ice cream and drinks at half the price of his competition. His foray was a huge success. Unfortunately, Feltman’s lessor also noticed this and raised his rent considerably at the end of his trial year. Feltman began searching for a better deal.

Feltman found out that Henry Ditmas, who had lost significant sums running a fleabag called the Washington Hotel, was not planning to renew his lease on a prime, sizeable lot. Feltman worked out a deal with Ditmas under which Ditmas renewed his lease and then sold his rights to Feltman for $3,800. Ditmas’ tract was across the Concourse from Sea Beach Palace, between West 10th Street and Jones Walk, near West 12th Street. The tract extended from the Concourse down to the ocean, with two-hundred feet of frontage along both. Over time, ocean currents also kept washing up more sand along Feltman’s beach, adding several acres to his new property over the years.

Seeing the possibilities afforded by his remarkable new lease, Feltman now embarked on a much more aggressive business plan. He would erect multiple buildings and establish a dining, lodging and entertainment complex.

Feltman believed it was necessary for the hotel, restaurant and entertainment venues to serve customers year-round and on weekdays to make the investment worthwhile. On weekends, he planned to attract conventions and the general public, and on weekdays, he planned to draw lodge and club meetings by offering them dining accommodations for them at reduced prices. However, West Brighton at the time was focused on the summer bathing season, and transportation schedules reflected this. Gunther’s Dummy Line was the only railroad to Coney Island at the time, and while it ran later trains on weekends, its last train back to Brooklyn on weekdays left at around 7:15 p.m. This was much too early for visitors to get to West Brighton and then have dinner, in an age when people worked 8 a.m. to 6 p.m., six days a week. Gunther was uninterested in running later trains just for Feltman, as were managers of the horsecar line. Feltman then sought out Culver just as he was about to build his new railroad, and gave his opinion that running a railway to Coney Island only for the summer weekend trade was uneconomical. If it rained on several summer weekends, the trains would run empty. Feltman promised that his lodge and club members would come year-round, rain or shine. Culver agreed with Feltman and set his last weekday trains out of West Brighton at 9:30 p.m. If things worked out as expected, Culver agreed to set the departure time at an even later hour.

Around 1870, a good five years before Culver entered the picture, Charles Feltman had a wholesale bakery in the Park Slope area of Brooklyn that was supplying bread, cake, and ice cream to the small hotels, food stands, and bathing pavilions that made up Coney Island in its early days. Feltman was a German immigrant who had come to America at a young age in search of opportunity. He had endured initial hardship, saved enough to become his own boss, and was now a capable businessman who was willing to take calculated risks. One of those risks had been his Brooklyn bakery, which he built in a then-undeveloped area on the expectation that southern Brooklyn would develop. His gamble paid off, and by the early 1870s, he was supplying two out of three bakery products sold at Coney Island.

For the 1875 season, Feltman established his own dining establishment directly in West Brighton, while still maintaining his wholesale bakery. He correctly estimated that the new venture would be quite profitable, based on the volumes his customers were ordering and the markups they were able to charge. Feltman leased a 16 foot by 25 foot shanty around Culver Plaza, erected a basic but more respectable lunch stand roughly double its size adjacent to it, and began quality clam roasts, ice cream and drinks at half the price of his competition. His foray was a huge success. Unfortunately, Feltman’s lessor also noticed this and raised his rent considerably at the end of his trial year. Feltman began searching for a better deal.

Feltman found out that Henry Ditmas, who had lost significant sums running a fleabag called the Washington Hotel, was not planning to renew his lease on a prime, sizeable lot. Feltman worked out a deal with Ditmas under which Ditmas renewed his lease and then sold his rights to Feltman for $3,800. Ditmas’ tract was across the Concourse from Sea Beach Palace, between West 10th Street and Jones Walk, near West 12th Street. The tract extended from the Concourse down to the ocean, with two-hundred feet of frontage along both. Over time, ocean currents also kept washing up more sand along Feltman’s beach, adding several acres to his new property over the years.

Seeing the possibilities afforded by his remarkable new lease, Feltman now embarked on a much more aggressive business plan. He would erect multiple buildings and establish a dining, lodging and entertainment complex.

Feltman believed it was necessary for the hotel, restaurant and entertainment venues to serve customers year-round and on weekdays to make the investment worthwhile. On weekends, he planned to attract conventions and the general public, and on weekdays, he planned to draw lodge and club meetings by offering them dining accommodations for them at reduced prices. However, West Brighton at the time was focused on the summer bathing season, and transportation schedules reflected this. Gunther’s Dummy Line was the only railroad to Coney Island at the time, and while it ran later trains on weekends, its last train back to Brooklyn on weekdays left at around 7:15 p.m. This was much too early for visitors to get to West Brighton and then have dinner, in an age when people worked 8 a.m. to 6 p.m., six days a week. Gunther was uninterested in running later trains just for Feltman, as were managers of the horsecar line. Feltman then sought out Culver just as he was about to build his new railroad, and gave his opinion that running a railway to Coney Island only for the summer weekend trade was uneconomical. If it rained on several summer weekends, the trains would run empty. Feltman promised that his lodge and club members would come year-round, rain or shine. Culver agreed with Feltman and set his last weekday trains out of West Brighton at 9:30 p.m. If things worked out as expected, Culver agreed to set the departure time at an even later hour.

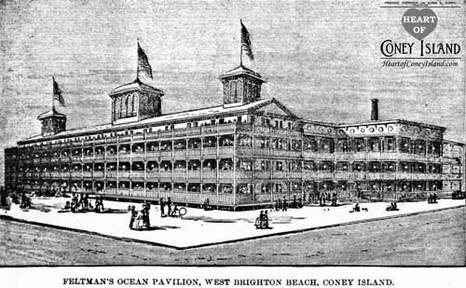

Feltman immediately hired McKane to build a three-building complex called the Ocean Pavilion, having been assured by Culver of year-round late-return railroad service. Feltman’s Ocean Pavilion consisted of a large hotel connected by passageways to two smaller additional general purpose buildings. The hotel itself was built first. It was three stories tall and ran fifty-five feet along the Concourse and 125 feet towards the ocean. The hotel had a bar and dining room on the main floor, and guest rooms on the two upper floors. Each floor had verandas, with sections set aside for dining. Food was delivered to the upper floors by means of dumbwaiters. The two additions were built next. Each was roughly the same height and extended twenty-five feet along the Concourse and 85 feet south. For the Ocean Pavilion’s first season, in 1876, Feltman hired Wannemacher’s 71st Regiment Band to play there, and added sung performance in 1877, a novelty at Coney Island. Having three smaller structures instead of one large one was to avoid the necessity of making major alterations if sections were to be converted for other purposes.

Over the next five or so years, Feltman continuously made additions to the complex, such that within ten years, he had the largest entertaining and dining venue in Coney Island.

A short distance to the south of the Ocean Pavilion, Feltman had McKane build a magnificent ballroom. Eventually, Feltman hoped to turn it into a theater. When the ballroom was not in use, it doubled as a convention hall, and an exhibition center in which visiting trade associations displayed their wares. Seventeen iron trusses, shaped like arches, were set parallel to each other to form the framework for the building, which had a 225 foot length and 45 foot width. From these trusses, 125 tons could be suspended to create balconies or entire floors, thereby obviating the necessity of building supporting pillars, which blocked the views of audiences. The ballroom was the epitome of elegance. Along the neat, ivory-colored plaster walls were elaborate, gilt sconces to highlight panels containing oil-painted murals of allegorical figures, of romantic sylvan scenes with backgrounds of castle ruins, and of groups of attractive young people in 18th Century dress, playing musical instruments or dancing, like delicate Lancret figures. The room also was illuminated by four-hundred gas-lights in amber-colored globes. Opinions varied as to whether Feltman's ballroom was artistically superior to Paul Bauer's dining room, but there was common agreement that both were beautiful.

Along the beach, Feltman erected a bathing pavilion, which also included a refreshments stand.

Over the next five or so years, Feltman continuously made additions to the complex, such that within ten years, he had the largest entertaining and dining venue in Coney Island.

A short distance to the south of the Ocean Pavilion, Feltman had McKane build a magnificent ballroom. Eventually, Feltman hoped to turn it into a theater. When the ballroom was not in use, it doubled as a convention hall, and an exhibition center in which visiting trade associations displayed their wares. Seventeen iron trusses, shaped like arches, were set parallel to each other to form the framework for the building, which had a 225 foot length and 45 foot width. From these trusses, 125 tons could be suspended to create balconies or entire floors, thereby obviating the necessity of building supporting pillars, which blocked the views of audiences. The ballroom was the epitome of elegance. Along the neat, ivory-colored plaster walls were elaborate, gilt sconces to highlight panels containing oil-painted murals of allegorical figures, of romantic sylvan scenes with backgrounds of castle ruins, and of groups of attractive young people in 18th Century dress, playing musical instruments or dancing, like delicate Lancret figures. The room also was illuminated by four-hundred gas-lights in amber-colored globes. Opinions varied as to whether Feltman's ballroom was artistically superior to Paul Bauer's dining room, but there was common agreement that both were beautiful.

Along the beach, Feltman erected a bathing pavilion, which also included a refreshments stand.

Feltman’s most famous and enduring creations, however, were his garden and restaurant. As a kid in Germany, he remembered visiting large outdoor dining establishments set among trees and gardens. Feltman bet that other immigrants would feel nostalgic about them as well.

He started by building a replica of a type of free-flowing garden known in architecture as a Deutscher Garten. He brought in tons of topsoil and planted bushes and flower-beds along paved walks. He placed three-hundred evergreen trees growing out of sod-boxes along these walks, later replacing them with maple trees rooted in the ground. Some of the walks branched off to shady glens and vine-covered trellises, where there were benches for those who preferred privacy.

On the east side of his grounds, Feltman then built a replica of a Bavarian inn and beer hall. Diners could have their meals in the building or on the grounds around it, and either in an open square or under trees in a grove. The food here was served by waiters dressed in native Bavarian dress. Some customers joked that Feltman expertly trained caterpillars to dive from tree branches into their beers, to ensure that customers would order fresh ones. All the while, diners listened to music played by military bands and orchestras that played waltzes. After a visit to Germany in late 1879, he imported entertainers from central Europe, such as the famous Tyrolian Warblers, an Austrian version of Swiss yodelers.

At the beginning, Feltman's diners were mostly Teutonic, but word spread quickly and his customers became more cosmopolitan. After a time, entertainers performed in English, and the music gradually changed from waltzes, polkas, and marches, to fox-trots, turkey-trots, and Lancers.

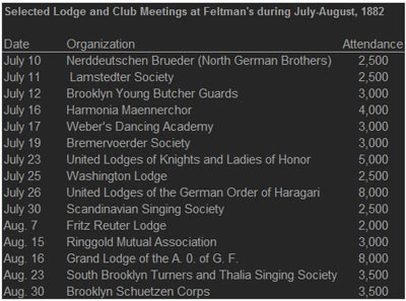

Feltman’s plan to get lodges to meet at his establishment started off slowly, and he was only able to book two events his second season. By 1882, however, the strategy had become a huge success. In addition to these sizable assemblages, there were conventions and almost nightly functions by smaller groups.

He started by building a replica of a type of free-flowing garden known in architecture as a Deutscher Garten. He brought in tons of topsoil and planted bushes and flower-beds along paved walks. He placed three-hundred evergreen trees growing out of sod-boxes along these walks, later replacing them with maple trees rooted in the ground. Some of the walks branched off to shady glens and vine-covered trellises, where there were benches for those who preferred privacy.

On the east side of his grounds, Feltman then built a replica of a Bavarian inn and beer hall. Diners could have their meals in the building or on the grounds around it, and either in an open square or under trees in a grove. The food here was served by waiters dressed in native Bavarian dress. Some customers joked that Feltman expertly trained caterpillars to dive from tree branches into their beers, to ensure that customers would order fresh ones. All the while, diners listened to music played by military bands and orchestras that played waltzes. After a visit to Germany in late 1879, he imported entertainers from central Europe, such as the famous Tyrolian Warblers, an Austrian version of Swiss yodelers.

At the beginning, Feltman's diners were mostly Teutonic, but word spread quickly and his customers became more cosmopolitan. After a time, entertainers performed in English, and the music gradually changed from waltzes, polkas, and marches, to fox-trots, turkey-trots, and Lancers.

Feltman’s plan to get lodges to meet at his establishment started off slowly, and he was only able to book two events his second season. By 1882, however, the strategy had become a huge success. In addition to these sizable assemblages, there were conventions and almost nightly functions by smaller groups.

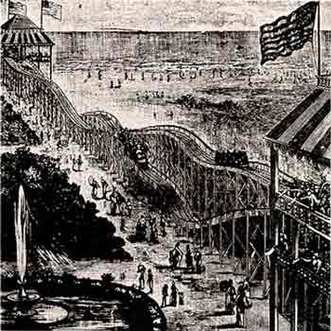

Feltman also catered to those of lesser means through foods stands. Most of those folks seemed to have a preference for sausage, or wienerwurst – the Americans called them weenies – but at ten cents each, he was not going to serve them on crockery. So, he hit on the idea of placing the sausage in a bread roll, adding a little mustard on top, some sauerkraut on top of that, and voila – the modern hot dog. Feltman sought the honor of having been the first to create this culinary delight, but former residents of Frankfurt, Germany, ridiculed Feltman's claim, saying it had been known as a frankfurter in their city long before Feltman was born. In any case, Feltman is credited with bringing the hot dog to the United States.

Some years later, the elaborate ballroom building was destroyed by fire, whereupon Feltman expanded his garden dining facilities into that area. He erected a narrow, two story structure that had no walls, but had a railing around the upper floor to prevent accidents. The main floor was for regular dinners, the upper one for clambakes. It was intended for fresh air dining, and provided protection from sun and rain. He also built, on ground level only, a new ballroom that had as much floor-space as the one destroyed by fire.

Feltman built a circular building along the Concourse (Surf Avenue) around 1903 to house the famous "Feltman Carousel," perhaps the greatest of all of Coney Island's carousels. The building is shown in the photo titled "Feltman's complex c. 1908" (several paragraphs above), and has a large advertising sign on top with a hand pointing to the Ziz roller coaster, another ride on Feltman's property (see below). This famous carousel was created by the legendary Coney Island amusement ride pioneer William Mangels and his master carver, Illions. The horses were beautifully and ornately hand-carved. Many prominent people are known to have ridden on Feltman’s carousel, including President William Howard Taft. President Taft weighed about three hundred pounds, and the story goes that after he finished riding, the wooden horse he had been on was found to have become ruptured. One source states that a real horse was used to turn the merry-go-round; but this seems unlikely as all European carousels were by this time powered by steam, which also provided the music, like the calliopes on the Mississippi showboats, and some carousels were already beginning to use electric power. Perhaps that source was referencing one of the older carousels that had been on the Feltman property, such as the carousel carved around 1880 by the famous carver Loof.

Feltman eventually installed a roller coaster, called the "Ziz - A Mile a Minute," around 1905 along the western end of his property, from Surf Avenue to the beach. The roller coaster was also built by Mangels. Today, the small tags that were given out as tickets, featuring an assortment of colorful characters, are valued by collectors.

When Feltman died in 1910, the business passed into the capable hands of his sons, Charles L. and Alfred. The name of their Deutscher Garten was changed to Maple Gardens during World War I when German troop atrocities reportedly-committed in Belgium and France evoked hostility in the United States towards all things German. When the United States entered the war, the German establishments in Coney Island had their names anglicized, and their walls, inside and out, were bedecked with American flags and red, white and blue bunting, so as to leave no doubt as to their allegiance.

Some years later, the elaborate ballroom building was destroyed by fire, whereupon Feltman expanded his garden dining facilities into that area. He erected a narrow, two story structure that had no walls, but had a railing around the upper floor to prevent accidents. The main floor was for regular dinners, the upper one for clambakes. It was intended for fresh air dining, and provided protection from sun and rain. He also built, on ground level only, a new ballroom that had as much floor-space as the one destroyed by fire.

Feltman built a circular building along the Concourse (Surf Avenue) around 1903 to house the famous "Feltman Carousel," perhaps the greatest of all of Coney Island's carousels. The building is shown in the photo titled "Feltman's complex c. 1908" (several paragraphs above), and has a large advertising sign on top with a hand pointing to the Ziz roller coaster, another ride on Feltman's property (see below). This famous carousel was created by the legendary Coney Island amusement ride pioneer William Mangels and his master carver, Illions. The horses were beautifully and ornately hand-carved. Many prominent people are known to have ridden on Feltman’s carousel, including President William Howard Taft. President Taft weighed about three hundred pounds, and the story goes that after he finished riding, the wooden horse he had been on was found to have become ruptured. One source states that a real horse was used to turn the merry-go-round; but this seems unlikely as all European carousels were by this time powered by steam, which also provided the music, like the calliopes on the Mississippi showboats, and some carousels were already beginning to use electric power. Perhaps that source was referencing one of the older carousels that had been on the Feltman property, such as the carousel carved around 1880 by the famous carver Loof.

Feltman eventually installed a roller coaster, called the "Ziz - A Mile a Minute," around 1905 along the western end of his property, from Surf Avenue to the beach. The roller coaster was also built by Mangels. Today, the small tags that were given out as tickets, featuring an assortment of colorful characters, are valued by collectors.

When Feltman died in 1910, the business passed into the capable hands of his sons, Charles L. and Alfred. The name of their Deutscher Garten was changed to Maple Gardens during World War I when German troop atrocities reportedly-committed in Belgium and France evoked hostility in the United States towards all things German. When the United States entered the war, the German establishments in Coney Island had their names anglicized, and their walls, inside and out, were bedecked with American flags and red, white and blue bunting, so as to leave no doubt as to their allegiance.

West Brighton enters the 1880s

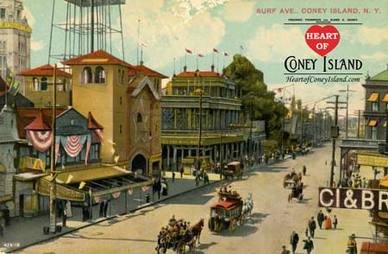

By 1882, West Brighton was proving to be a formidable force in its competition with Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach. Immense crowds to arrive at West Brighton that season, by train every fifteen minutes, and by steamer every thirty minutes. In the daytime, Surf Avenue was a riot of color. American flags, red-white-and-blue bunting, and thousands of silk pennants gladdened the sight of those arriving. The two iron piers, Bauer's, Feltman’s, Sea Beach Palace, and a host of other establishments had long lines of people in front of them waiting to enter. Bands and orchestras contributed to the festive air with a Johann Strauss, Jr., waltz, a Sousa march, or a saucy piece by Offenbach. At night, Surf Avenue had a magical glow from gas and electric lights in colored globes along with Japanese lanterns. Thousands of couples thronged Coney's many ballrooms, while thousands of others engaged in the less strenuous activity of consuming the culinary delicacies in its numerous restaurants, or admired the talents of its cabaret performers between drinks.

By this time, West Brighton was expanding westward of Culver Plaza. Surf Avenue had been extended to West 17th Street in 1881, and it now reached Norton’s Point at the westernmost part of Coney Island with subsequent construction. Though Surf Avenue was an extension of the Concourse westward from Culver Plaza, it was at this time surfaced with gravel, unlike the Concourse, which was covered with asphalt all the way to Engeman's Ocean Hotel in Brighton. At the west end, things were still comparatively subdued, as Mike Norton's health was giving out, and, consequently, his hotel was boarded up.

The three competing sections of Coney Island were also becoming more interconnected overall. Around 1885, a railroad spur was constructed from the Brighton terminal to the west side of Cable's Hotel at Culver Plaza North. This rail connection, called the Sea View Railroad, ran at ground level and on steel bridges in marshy areas. A person could now travel by rail from the eastern to western tip of Coney Island by taking the Marine Railroad to the Manhattan Hotel, the shuttle to the Brighton Beach Hotel, the Sea View line to Culver Plaza North, and the Culver spur to Norton's Point.

Overall, the future looked bright for West Brighton, as Reverend Stockwell remarked in his 1884 book, ‘History of the Town of Gravesend’:

‘And thus our growth continues; and, we venture to say, that no village in Kings County can show a better record of material prosperity in the past few years, or brighter prospects for the future. With the great bridge [Brooklyn Bridge, 1870] uniting the two largest cities of America [New York and Brooklyn, actually largest and third-largest]… and the problem of rapid transit about to be solved; it is not rash to prophesy, for this part of Long Island [Brooklyn], at no distant day, a future which will far eclipse the wildest dreams of its most enthusiastic inhabitant.’

By 1882, West Brighton was proving to be a formidable force in its competition with Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach. Immense crowds to arrive at West Brighton that season, by train every fifteen minutes, and by steamer every thirty minutes. In the daytime, Surf Avenue was a riot of color. American flags, red-white-and-blue bunting, and thousands of silk pennants gladdened the sight of those arriving. The two iron piers, Bauer's, Feltman’s, Sea Beach Palace, and a host of other establishments had long lines of people in front of them waiting to enter. Bands and orchestras contributed to the festive air with a Johann Strauss, Jr., waltz, a Sousa march, or a saucy piece by Offenbach. At night, Surf Avenue had a magical glow from gas and electric lights in colored globes along with Japanese lanterns. Thousands of couples thronged Coney's many ballrooms, while thousands of others engaged in the less strenuous activity of consuming the culinary delicacies in its numerous restaurants, or admired the talents of its cabaret performers between drinks.

By this time, West Brighton was expanding westward of Culver Plaza. Surf Avenue had been extended to West 17th Street in 1881, and it now reached Norton’s Point at the westernmost part of Coney Island with subsequent construction. Though Surf Avenue was an extension of the Concourse westward from Culver Plaza, it was at this time surfaced with gravel, unlike the Concourse, which was covered with asphalt all the way to Engeman's Ocean Hotel in Brighton. At the west end, things were still comparatively subdued, as Mike Norton's health was giving out, and, consequently, his hotel was boarded up.