Coney Island History: The Story of the Bowery at West Brighton

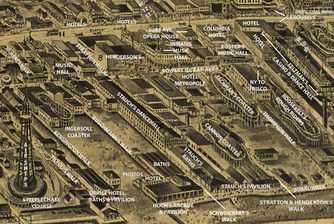

Close-up of 1905 map showing the Bowery section, which by then was far less seedy.

Close-up of 1905 map showing the Bowery section, which by then was far less seedy.

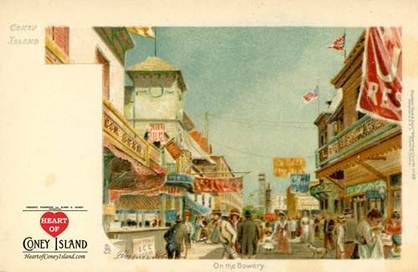

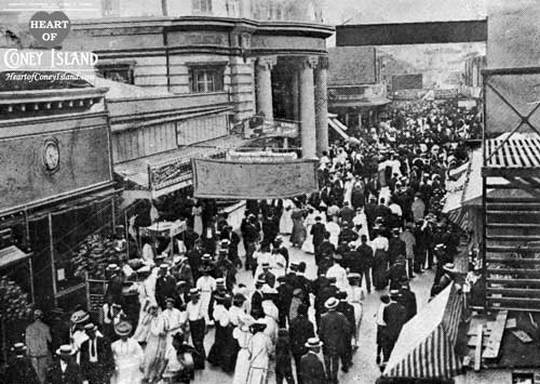

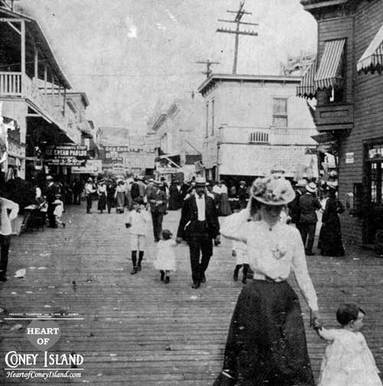

The most famous section of West Brighton was an area known as the Bowery. The Bowery was south of Surf Avenue and extended from Jones Walk, on the west side of Feltman’s, to West 16th Street, on the east side of Steeplechase Park. Its main drag, known as Ocean Avenue until around 1905 and as Bowery Lane thereafter, ran parallel to Surf Ocean and about 65 yards south of it. The Tilyou and Stratton families had leases to much of the land, and they are believed to have originally constructed a boardwalk along this lane, which was later replaced by a paved walk. The original name of Ocean Avenue must have led to some confusion in the Postal Service as there was another Ocean Avenue in nearby Sheepshead Bay.

The Bowery was a raucous area where police frequently looked the other way as drinking, gambling, music and shows took place well into the night. Coney Island's appeal was that anyone could find the type of experience they desired. For those looking for more variety and fun, and less refinement, the Bowery stood head and shoulders above Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach.

The Bowery came into its prime a little later than the rest of West Brighton, Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach. During the 1870s and 1880s, it was overshadowed by the large hotels in these other areas, and offered somewhat seedy and smaller-scale entertainment. By around 1905, it had become a primary destination within West Brighton and Coney Island.

The Bowery was a raucous area where police frequently looked the other way as drinking, gambling, music and shows took place well into the night. Coney Island's appeal was that anyone could find the type of experience they desired. For those looking for more variety and fun, and less refinement, the Bowery stood head and shoulders above Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach.

The Bowery came into its prime a little later than the rest of West Brighton, Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach. During the 1870s and 1880s, it was overshadowed by the large hotels in these other areas, and offered somewhat seedy and smaller-scale entertainment. By around 1905, it had become a primary destination within West Brighton and Coney Island.

Tilyou's Property, Ravenhall's and McPherson's Hotel (1870s)

From one end of the Bowery Lane to the other, and on both sides of it, establishments were crowded together, elbow to elbow, as it were. Beyond its west end, at West 16th Street, was Peter Tilyou's holdings, where he was to build, some years later, his Steeplechase Park, after acquiring adjoining land to West 19th Street. From West 19th to West 20th Streets was Richard Ravenhall's hotel, built in 1863 and the first to be open throughout the year. When snow was on the ground, affluent residents of Brooklyn would come by sleigh to the beach to dine in Ravenhall's attractive restaurant. Westward from Ravenhall's inn was a scattering of small, wooden hotels and bathing pavilions, the most notable of which was McPherson's Point Comfort Hotel, between West 36th and West 37th Streets. While the dining establishments in West Brighton were mostly German in ownership and cuisine, and attracted largely a foreign, middle-class trade, those to the west, like their wealthier brethren at the east end, were owned and patronized mainly by an Anglo-American, middle-class clientele. Virtually all the hotels to the west were on the south side of what was to become Surf Avenue.

From one end of the Bowery Lane to the other, and on both sides of it, establishments were crowded together, elbow to elbow, as it were. Beyond its west end, at West 16th Street, was Peter Tilyou's holdings, where he was to build, some years later, his Steeplechase Park, after acquiring adjoining land to West 19th Street. From West 19th to West 20th Streets was Richard Ravenhall's hotel, built in 1863 and the first to be open throughout the year. When snow was on the ground, affluent residents of Brooklyn would come by sleigh to the beach to dine in Ravenhall's attractive restaurant. Westward from Ravenhall's inn was a scattering of small, wooden hotels and bathing pavilions, the most notable of which was McPherson's Point Comfort Hotel, between West 36th and West 37th Streets. While the dining establishments in West Brighton were mostly German in ownership and cuisine, and attracted largely a foreign, middle-class trade, those to the west, like their wealthier brethren at the east end, were owned and patronized mainly by an Anglo-American, middle-class clientele. Virtually all the hotels to the west were on the south side of what was to become Surf Avenue.

Entertainment in The Bowery (1870s)

The Bowery was relatively small but was packed with entertainment. On both sides of Bowery Lane, and along side-alleys, one and two story wooden buildings were erected. They housed mostly saloons, concert halls, and a few first class restaurants. The concert halls in no way remotely resembled Carnegie Hall. Most of them were honky-tonks, and the only concerts given were those by a lone piano player, who sat alongside a stage and accompanied a chanteuse and her chantootsies; the latter being mostly over-the-hill chorus girls. The usual set-up of these concert halls was a stage at the opposite side of the entrance, a bar, tables and chairs, a dance space, and a screened doorway leading to rooms on the upper floor. While the burlesque queen would belt out her bawdy songs, her companions would sing along, then engage in sexually suggestive movements that passed for dancing. When they finished their routine, they would circulate around the bar and tables, during which another group of girls would take their places on the stage. After the Jezebels paired up with prosperous-looking customers, and got them to spend freely on drinks, they would ask the expected question with a demure smile, as to whether he would like to come upstairs to her room and have his fortune told by her. What gentleman could refuse an offer like that? There was, of course, an extra charge for such a personalized service and attentiveness.

Some concert hall owners eschewed the use of fortune telling on their premises, either out of a sense of propriety, or because they didn't have an upper floor. A few felt that they would avoid troublemakers by having tap-dancers, and a pretty young thing singing sentimental tunes. This type of entertainment went over big in Irish establishments of the better type. After each song, a shower of coins and rolled-up dollar bills would descend on the stage, and when her act was finished, a young fellow would come on the stage, gather the money into a basket, bow to the singer, and present it to her. She would accept it with a curtsy, throw kisses to her appreciative audience, and gracefully make her exit. The money thus gathered would be apportioned between the singer and the piano player.

The Bowery was relatively small but was packed with entertainment. On both sides of Bowery Lane, and along side-alleys, one and two story wooden buildings were erected. They housed mostly saloons, concert halls, and a few first class restaurants. The concert halls in no way remotely resembled Carnegie Hall. Most of them were honky-tonks, and the only concerts given were those by a lone piano player, who sat alongside a stage and accompanied a chanteuse and her chantootsies; the latter being mostly over-the-hill chorus girls. The usual set-up of these concert halls was a stage at the opposite side of the entrance, a bar, tables and chairs, a dance space, and a screened doorway leading to rooms on the upper floor. While the burlesque queen would belt out her bawdy songs, her companions would sing along, then engage in sexually suggestive movements that passed for dancing. When they finished their routine, they would circulate around the bar and tables, during which another group of girls would take their places on the stage. After the Jezebels paired up with prosperous-looking customers, and got them to spend freely on drinks, they would ask the expected question with a demure smile, as to whether he would like to come upstairs to her room and have his fortune told by her. What gentleman could refuse an offer like that? There was, of course, an extra charge for such a personalized service and attentiveness.

Some concert hall owners eschewed the use of fortune telling on their premises, either out of a sense of propriety, or because they didn't have an upper floor. A few felt that they would avoid troublemakers by having tap-dancers, and a pretty young thing singing sentimental tunes. This type of entertainment went over big in Irish establishments of the better type. After each song, a shower of coins and rolled-up dollar bills would descend on the stage, and when her act was finished, a young fellow would come on the stage, gather the money into a basket, bow to the singer, and present it to her. She would accept it with a curtsy, throw kisses to her appreciative audience, and gracefully make her exit. The money thus gathered would be apportioned between the singer and the piano player.

The Concourse becomes Surf Avenue (1879)

Surf Avenue had existed as a nameless road from about 1740. In early times, roads through sparsely settled land usually consisted of some parallel hitching posts along both sides to indicate their course. Such was the condition of the road west of Culver Plaza. East of this plaza, the Concourse had been built in 1876, a year before the new Ocean Parkway reached it. The Concourse was an asphalt road, with newly constructed sidewalks, extending eastward to Engeman's Ocean Hotel in Brighton Beach. By 1879, the Concourse had been extended to the west end, and the name of the entire street was changed to Surf Avenue, though the section from Ocean Parkway to the Ocean Hotel retained the name of Concourse. The reason why the Concourse got an asphalt surfacing, whereas Ocean Parkway did not, was that drifting sand from the beach, especially in the winter, covered the roadway, and it was more easily cleared from a smoother surface than from a rougher one.

Surf Avenue had existed as a nameless road from about 1740. In early times, roads through sparsely settled land usually consisted of some parallel hitching posts along both sides to indicate their course. Such was the condition of the road west of Culver Plaza. East of this plaza, the Concourse had been built in 1876, a year before the new Ocean Parkway reached it. The Concourse was an asphalt road, with newly constructed sidewalks, extending eastward to Engeman's Ocean Hotel in Brighton Beach. By 1879, the Concourse had been extended to the west end, and the name of the entire street was changed to Surf Avenue, though the section from Ocean Parkway to the Ocean Hotel retained the name of Concourse. The reason why the Concourse got an asphalt surfacing, whereas Ocean Parkway did not, was that drifting sand from the beach, especially in the winter, covered the roadway, and it was more easily cleared from a smoother surface than from a rougher one.

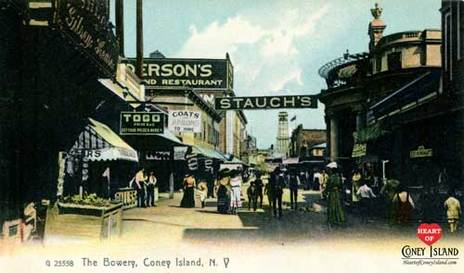

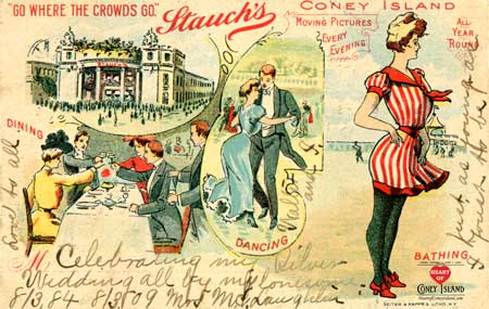

The Story of Louis Stauch and Stauch's Restaurant and Dance Hall (c. 1880-1929)

At this time, around 1880, Louis Stauch was a young fellow trying to make his way in the world. Although of a poor family, he had learned to play the piano, and was earning a living tickling the keys at social functions. This young piano player would turn out to be among the most honorable and hardworking of the immigrants who settled at West Brighton, a true testament to the pursuit of the American Dream.

One summer evening, he was engaged to play at a wedding in the Bath Beach area, several miles from Coney Island. Through a misunderstanding, he thought that he would have a place to stay overnight after the wedding. Unable to find sleeping quarters in the vicinity, he decided to walk to Coney Island, where he had never been before, and slept on the beach.

The following day, while he was eating at a small coffee shop with a dance space along the beach, he overheard some couples ask the owner if he could put on his piano player so that they might dance. Hearing that the piano player hadn't shown up yet, Stauch volunteered his services. After the dancers left, the owner hired Stauch to play there permanently.

Stauch was hardworking and financially responsible, and gradually saved up enough money to buy the cafe he worked at. He subsequently expanded it, little by little, and gradually prospered.

In 1896, at age thirty-six, Lou married a twenty-five year old floozy named Matilda. For the next quarter of a century, Lou worked seven days a week in his establishment without ever taking a vacation. He made money, and Matilda banked it, in her name.

Following the Fire of 1903, which destroyed Stauch's wooden establishment, he rebuilt entirely in brick. By adding rooftop water tanks that could soak the exterior of his new building and slow the spread of fire if a nearby establishment caught fire, he was also able to obtain fire insurance, a rarity at the time. Henderson's did likewise, and both establishments were ready for business in time for the start of the 1904 season.

Years later, in 1921, Matilda walked out on Lou, bankbooks and all, and with her walked Lou's maître d', Grover Muller. Lou wanted to sue for divorce, but Matilda was always one step ahead of the process-servers. Finally, after eight months, she was served with papers while she was with Muller at the Empire State Racetrack, in Yonkers. A former housekeeper in Lou's home revealed that Matilda had bestowed her favors, prior to meeting Muller, on Charlie Miller, an erstwhile chauffeur of the Stauchs, and, earlier, on Thomas Penfold, a singer in Lou's restaurant. She must have been very impressed with Thomas' voice, for she bought him two racehorses, with poor Lou's dough. It is likely that these three characters represented only the tip of the iceberg in Matilda's assignations. Upon obtaining a divorce from her in 1922, Lou sold all his property in Coney Island for about $500,000, and retired. Fortunately, his Coney Island holdings had not been put in her name.

Instead of becoming embittered and reclusive by such a disheartening experience, he spent much of his retirement in visiting hospitals in Brooklyn, bringing gifts for sick children, and helping poor families with money and food, He contributed to many charities, including a fund for families of policemen killed in the line of duty. Lou died in 1929, leaving most of his estate to his sister. Joseph Huber, of the Otto Huber Brewery, which produced Coney Island's favorite beer, Golden Rod, was named by Lou as co-executor of his will, along with his sister. Among Lou's bequests was one to the Brooklyn Hebrew Orphan Asylum, and another to Coney island's Lutheran Church, of which he was a parishioner. Louis Stauch truly deserved someone better than Matilda, but still managed to make lemonade when life gave him a lemon.

At this time, around 1880, Louis Stauch was a young fellow trying to make his way in the world. Although of a poor family, he had learned to play the piano, and was earning a living tickling the keys at social functions. This young piano player would turn out to be among the most honorable and hardworking of the immigrants who settled at West Brighton, a true testament to the pursuit of the American Dream.

One summer evening, he was engaged to play at a wedding in the Bath Beach area, several miles from Coney Island. Through a misunderstanding, he thought that he would have a place to stay overnight after the wedding. Unable to find sleeping quarters in the vicinity, he decided to walk to Coney Island, where he had never been before, and slept on the beach.

The following day, while he was eating at a small coffee shop with a dance space along the beach, he overheard some couples ask the owner if he could put on his piano player so that they might dance. Hearing that the piano player hadn't shown up yet, Stauch volunteered his services. After the dancers left, the owner hired Stauch to play there permanently.

Stauch was hardworking and financially responsible, and gradually saved up enough money to buy the cafe he worked at. He subsequently expanded it, little by little, and gradually prospered.

In 1896, at age thirty-six, Lou married a twenty-five year old floozy named Matilda. For the next quarter of a century, Lou worked seven days a week in his establishment without ever taking a vacation. He made money, and Matilda banked it, in her name.

Following the Fire of 1903, which destroyed Stauch's wooden establishment, he rebuilt entirely in brick. By adding rooftop water tanks that could soak the exterior of his new building and slow the spread of fire if a nearby establishment caught fire, he was also able to obtain fire insurance, a rarity at the time. Henderson's did likewise, and both establishments were ready for business in time for the start of the 1904 season.

Years later, in 1921, Matilda walked out on Lou, bankbooks and all, and with her walked Lou's maître d', Grover Muller. Lou wanted to sue for divorce, but Matilda was always one step ahead of the process-servers. Finally, after eight months, she was served with papers while she was with Muller at the Empire State Racetrack, in Yonkers. A former housekeeper in Lou's home revealed that Matilda had bestowed her favors, prior to meeting Muller, on Charlie Miller, an erstwhile chauffeur of the Stauchs, and, earlier, on Thomas Penfold, a singer in Lou's restaurant. She must have been very impressed with Thomas' voice, for she bought him two racehorses, with poor Lou's dough. It is likely that these three characters represented only the tip of the iceberg in Matilda's assignations. Upon obtaining a divorce from her in 1922, Lou sold all his property in Coney Island for about $500,000, and retired. Fortunately, his Coney Island holdings had not been put in her name.

Instead of becoming embittered and reclusive by such a disheartening experience, he spent much of his retirement in visiting hospitals in Brooklyn, bringing gifts for sick children, and helping poor families with money and food, He contributed to many charities, including a fund for families of policemen killed in the line of duty. Lou died in 1929, leaving most of his estate to his sister. Joseph Huber, of the Otto Huber Brewery, which produced Coney Island's favorite beer, Golden Rod, was named by Lou as co-executor of his will, along with his sister. Among Lou's bequests was one to the Brooklyn Hebrew Orphan Asylum, and another to Coney island's Lutheran Church, of which he was a parishioner. Louis Stauch truly deserved someone better than Matilda, but still managed to make lemonade when life gave him a lemon.

A Young Harry Houdini Performs at Vacca's West End Casino (1894)

By now, the Bowery was attracting all types of performers and sideshow personalities. In 1894, a 20-year-old Harry Houdini was stunning audiences, including his future wife, at Vacca's, located close to Stauch's, on the southeast corner of Ocean Avenue (Bowery Lane) and Buschmann's Walk. Harry also likely performed at Sea Beach Palace. A broader account of Houdini at Coney Island is in the West Brighton article.

By now, the Bowery was attracting all types of performers and sideshow personalities. In 1894, a 20-year-old Harry Houdini was stunning audiences, including his future wife, at Vacca's, located close to Stauch's, on the southeast corner of Ocean Avenue (Bowery Lane) and Buschmann's Walk. Harry also likely performed at Sea Beach Palace. A broader account of Houdini at Coney Island is in the West Brighton article.

The Bowery Fire of 1894

There was rarely a dull moment and Coney Island, and 1894 proved to be no exception. Amid all the political turmoil that was taking place at Coney Island in 1893 and 1894, thanks to John McKane's latest rigging scandal, on April 8, 1894, before the season began, a fire broke out in the Bowery. It destroyed Perry's Glass Pavilion and Connor's Alhambra. Both were cabaret-style concert halls. Other structural casualties were Kenny Sutherland's bar, and two restaurants, Joe's, and Olney's. Reformers were undoubtedly elated by the destruction. Three days later, just about when the embers had ceased smoking, a ferocious gale struck, inflicting significant damage on neighboring Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach.

There was rarely a dull moment and Coney Island, and 1894 proved to be no exception. Amid all the political turmoil that was taking place at Coney Island in 1893 and 1894, thanks to John McKane's latest rigging scandal, on April 8, 1894, before the season began, a fire broke out in the Bowery. It destroyed Perry's Glass Pavilion and Connor's Alhambra. Both were cabaret-style concert halls. Other structural casualties were Kenny Sutherland's bar, and two restaurants, Joe's, and Olney's. Reformers were undoubtedly elated by the destruction. Three days later, just about when the embers had ceased smoking, a ferocious gale struck, inflicting significant damage on neighboring Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach.

The Bowery Fire of 1899

On May 26, 1899, Coney Island was ravaged again by a fire that raged between the Bowery and the ocean, from Sea Beach Walk, near West 8th Street, to Kensington Walk, about eight blocks to the west. Only one block of the Bowery itself was destroyed, but sixty buildings were destroyed. Among them were Feltman's grand casino and his ornate ballroom, Louis Stauch's restaurant and dance hall, and Henry Henderson's Bathing Pavilion, the largest in Coney Island.

What was particularly distressing to the owners of the largely uninsured buildings was that this particular fire occurred only a few days before the beginning of the season, which compelled them to improvise hurriedly and slap together some boards in an effort to salvage a part of the season. When a fire occurred off season, they had time to rebuild properly and be in a position to retrieve their losses in the following summer.

On May 26, 1899, Coney Island was ravaged again by a fire that raged between the Bowery and the ocean, from Sea Beach Walk, near West 8th Street, to Kensington Walk, about eight blocks to the west. Only one block of the Bowery itself was destroyed, but sixty buildings were destroyed. Among them were Feltman's grand casino and his ornate ballroom, Louis Stauch's restaurant and dance hall, and Henry Henderson's Bathing Pavilion, the largest in Coney Island.

What was particularly distressing to the owners of the largely uninsured buildings was that this particular fire occurred only a few days before the beginning of the season, which compelled them to improvise hurriedly and slap together some boards in an effort to salvage a part of the season. When a fire occurred off season, they had time to rebuild properly and be in a position to retrieve their losses in the following summer.

The Bowery Gentrifies: The Evolution of Entertainment (1901)

By the turn of the century, the Bowery had undergone quite a transformation from its early days, twenty-five years earlier. As an example of how the Bowery had cleaned up its entertainment, in 1901, at West Brighton's Bowery, Henry Henderson's Music Hall was presenting operettas by Gilbert and Sullivan, including The Mikado, and His Majesty's Ship, Pinafore. Henderson's soon switched to a vaudeville format, changing programs weekly. The Bowery was becoming a place where respectable people could go for respectable entertainment.

By the turn of the century, the Bowery had undergone quite a transformation from its early days, twenty-five years earlier. As an example of how the Bowery had cleaned up its entertainment, in 1901, at West Brighton's Bowery, Henry Henderson's Music Hall was presenting operettas by Gilbert and Sullivan, including The Mikado, and His Majesty's Ship, Pinafore. Henderson's soon switched to a vaudeville format, changing programs weekly. The Bowery was becoming a place where respectable people could go for respectable entertainment.

Fiery Passions and the 'Cleansing' Fire of 1903

On November 1, 1903, just a couple of months after nearby Luna Park had wrapped up its inaugural season, one of the worst fires in Coney Island's history consumed over 260 buildings. It began in the Albatross Hotel, at the west end of the Bowery, and was carried by the wind eastward to Jones Walk. It was prevented from going further by a brick wall that Feltman had wisely built after the 1899 fire to protect his property from the fire-prone wooden Bowery buildings. Every structure in the Bowery was destroyed, and almost every building between Surf Avenue and the beach was burned. The fire is said to have been set by a former employee of the Albatross Hotel because of unrequited love for a female employee who preferred the attentions of the hotel's owner.

The reform element at Coney Island, which still hated the Bowery because of its less-than-Puritan venues, was predictably not overly disappointed to see the whole area burn down. So what if 'a thousand women and children [were] rendered homeless, and many could be seen wandering around the streets of Coney Island... [having] lost their all, not saving anything in the way of clothing except what they wore'? Only Satan's emissaries would inhabit a place like the Bowery in any case. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle additionally reported 'many thrilling scenes' took place during the fire that caused 'more than $1,000,000 damage' and swept away five entire city blocks. It is no wonder that shows like the Johnstown Flood were popular in this era.

On November 1, 1903, just a couple of months after nearby Luna Park had wrapped up its inaugural season, one of the worst fires in Coney Island's history consumed over 260 buildings. It began in the Albatross Hotel, at the west end of the Bowery, and was carried by the wind eastward to Jones Walk. It was prevented from going further by a brick wall that Feltman had wisely built after the 1899 fire to protect his property from the fire-prone wooden Bowery buildings. Every structure in the Bowery was destroyed, and almost every building between Surf Avenue and the beach was burned. The fire is said to have been set by a former employee of the Albatross Hotel because of unrequited love for a female employee who preferred the attentions of the hotel's owner.

The reform element at Coney Island, which still hated the Bowery because of its less-than-Puritan venues, was predictably not overly disappointed to see the whole area burn down. So what if 'a thousand women and children [were] rendered homeless, and many could be seen wandering around the streets of Coney Island... [having] lost their all, not saving anything in the way of clothing except what they wore'? Only Satan's emissaries would inhabit a place like the Bowery in any case. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle additionally reported 'many thrilling scenes' took place during the fire that caused 'more than $1,000,000 damage' and swept away five entire city blocks. It is no wonder that shows like the Johnstown Flood were popular in this era.

The Golden Era of Stauch's and Henderson's (c. 1905)

Ironically, the fire of 1903 resulted in changes in the Bowery which made it even more popular thereafter. As Brooklyn Borough's President Swanstrom commented, 'The fire at Coney Island, while a great hardship to the unfortunate people who lost their property, will be a blessing in the long run... [f]ire is one of the best purifiers'. Both city officials and business owners agreed that the Bowery street itself had to be widened by sixty feet. This would hamper the ability of a fire to spread from one side to the other as easily, but also made the area much more inviting and increased visitor capacity.

Additionally, major establishments like Stauch's and Henderson's, both of which had been totally destroyed, used the opportunity to rebuild using brick instead of wood. This gave the Bowery a more modern feel. To prevent future fires and qualify for fire insurance, both establishments also installed rooftop water tanks that could be released onto their roofs in the case of nearby fires. Stauch's rebuilt restaurant and ballroom presented an elegant atmosphere for dining and dancing.

On the northeast corner of the Bowery and Stillwell Avenues, diagonally opposite Stauch's restaurant, Henry Henderson erected a new brick theatre, named Henderson's Music Hall. He also built a new Sea Side Hotel to replace the one destroyed. This hotel was connected to the theatre, and contained on the main floor a restaurant and a cabaret. When Henry Henderson died, his son, Frederick, took over the management of the property. He presented not only variety acts in the Music Hall, but floor shows in his cabaret. In booking vaudeville acts for his Music Hall, Fred became associated with the Keith-Orpheum circuit, of which he eventually became an executive.

In 1909, a familiar name appeared among the vaudeville acts in Henderson's Music Hall. Jules Levy, the cornet virtuoso who had played in the Manhattan Beach band shortly after Corbin opened his hotel, and who had died in 1903, left a wife and two sons. She had been an opera singer, and was still in good voice. One son had become a cornetist, the other, a violinist. They now appeared at Henderson's as a trio, and were warmly greeted at each performance. Some coming to hear them sought perhaps to recapture memories of thirty years past, and some came to hear whether the son was as good a cornetist as the father had been.

Ironically, the fire of 1903 resulted in changes in the Bowery which made it even more popular thereafter. As Brooklyn Borough's President Swanstrom commented, 'The fire at Coney Island, while a great hardship to the unfortunate people who lost their property, will be a blessing in the long run... [f]ire is one of the best purifiers'. Both city officials and business owners agreed that the Bowery street itself had to be widened by sixty feet. This would hamper the ability of a fire to spread from one side to the other as easily, but also made the area much more inviting and increased visitor capacity.

Additionally, major establishments like Stauch's and Henderson's, both of which had been totally destroyed, used the opportunity to rebuild using brick instead of wood. This gave the Bowery a more modern feel. To prevent future fires and qualify for fire insurance, both establishments also installed rooftop water tanks that could be released onto their roofs in the case of nearby fires. Stauch's rebuilt restaurant and ballroom presented an elegant atmosphere for dining and dancing.

On the northeast corner of the Bowery and Stillwell Avenues, diagonally opposite Stauch's restaurant, Henry Henderson erected a new brick theatre, named Henderson's Music Hall. He also built a new Sea Side Hotel to replace the one destroyed. This hotel was connected to the theatre, and contained on the main floor a restaurant and a cabaret. When Henry Henderson died, his son, Frederick, took over the management of the property. He presented not only variety acts in the Music Hall, but floor shows in his cabaret. In booking vaudeville acts for his Music Hall, Fred became associated with the Keith-Orpheum circuit, of which he eventually became an executive.

In 1909, a familiar name appeared among the vaudeville acts in Henderson's Music Hall. Jules Levy, the cornet virtuoso who had played in the Manhattan Beach band shortly after Corbin opened his hotel, and who had died in 1903, left a wife and two sons. She had been an opera singer, and was still in good voice. One son had become a cornetist, the other, a violinist. They now appeared at Henderson's as a trio, and were warmly greeted at each performance. Some coming to hear them sought perhaps to recapture memories of thirty years past, and some came to hear whether the son was as good a cornetist as the father had been.

This article combines the author's extensive ongoing research with the text of the late Manny Teitelman's unpublished manuscript, 'Coney Island, Last Stop!'

The manuscript's contents are used, modified and published under an exclusive copyright license dated 2016. All rights reserved.

The manuscript's contents are used, modified and published under an exclusive copyright license dated 2016. All rights reserved.

Return to Coney Island History Homepage